No One Lives Forever 2 Deut. serial key or number

No One Lives Forever 2 Deut. serial key or number

Ecclesiastes

Ecclesiastes (/ɪˌkliːziˈæstiːz/; Hebrew: קֹהֶלֶת, qōheleṯ, Greek: Ἐκκλησιαστής, Ekklēsiastēs) is one of the 24 books of the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), where it is classified as one of the Ketuvim (Writings). Originally written c. 450–200 BCE, it is also among the canonical works of wisdom literature of the Old Testament in most denominations of Christianity. The title Ecclesiastes is a Latin transliteration of the Greek translation of the Hebrew Kohelet (also written as Koheleth, Qoheleth or Qohelet), the pseudonym used by the author of the book.

In traditional Jewish texts and throughout Christian church history (up to the 18th and 19th centuries), King Solomon is named as the author, but modern scholars reject this. The book is presented as the musings of a king of Jerusalem as he relates his experiences and draws lessons from them that are often self-critical. The author, who is not named anywhere in the book or anywhere else in the Bible, introduces a "Kohelet" whom he identifies as the son of David (1:1). The author does not use his own voice again until the final verses (12:9–14), where he gives his own thoughts and summarises the statements of the "Kohelet". The book emphatically proclaims that all the actions of human beings are inherently hevel, meaning "vapor" or "breath", but often interpreted as "insubstantial", "vain", or "futile", since the lives of both wise and foolish people all end in death. While Qoheleth clearly endorses wisdom as a means for a well-lived earthly life, he is unable to ascribe eternal meaning to it. In light of this perceived senselessness, he suggests that human beings should enjoy the simple pleasures of daily life, such as eating, drinking, and taking enjoyment in one's work, which are gifts from the hand of God. The book concludes with the injunction to "Fear God, and keep his commandments; for that is the whole duty of everyone". However, the lines are likely a later insertion meant to support the book's orthodoxy despite its overarching existential concerns (12:13).[1]

Title[edit]

Ecclesiastes is a phonetic transliteration of the Greek word Ἐκκλησιαστής (Ekklesiastes), which in the Septuagint translates the Hebrew name of its stated author, Kohelet (קֹהֶלֶת). The Greek word derives from ekklesia (assembly)[2] as the Hebrew word derives from kahal (assembly),[3] but while the Greek word means 'member of an assembly',[4] the meaning of the original Hebrew word it translates is less certain.[5] As Strong's concordance mentions,[6] it is a female active participle of the verb kahal in its simple (Qal) paradigm, a form not used elsewhere in the Bible and which is sometimes understood as active or passive depending on the verb,[7] so that Kohelet would mean '(female) assembler' in the active case (recorded as such by Strong's concordance,[6]) and '(female) assembled, member of an assembly' in the passive case (as per the Septuagint translators). According to the majority understanding today,[5] the word is a more general (mishkal קוֹטֶלֶת) form rather than a literal participle, and the intended meaning of Kohelet in the text is 'someone speaking before an assembly', hence 'Teacher' or 'Preacher'.

Structure[edit]

Ecclesiastes is presented as biography of "Kohelet" or "Qoheleth"; his story is framed by the voice of the narrator, who refers to Kohelet in the third person, praises his wisdom, but reminds the reader that wisdom has its limitations and is not man's main concern.[8] Kohelet reports what he planned, did, experienced and thought, but his journey to knowledge is, in the end, incomplete; the reader is not only to hear Kohelet's wisdom, but to observe his journey towards understanding and acceptance of life's frustrations and uncertainties: the journey itself is important.[9]

Few of the many attempts to uncover an underlying structure to Ecclesiastes have met with widespread acceptance; among them, the following is one of the more influential:[10]

- Title (1:1)

- Initial poem (1:2–11)

- I: Kohelet's investigation of life (1:12–6:9)

- II: Kohelet's conclusions (6:10–11:6)

- Introduction (6:10–12)

- A: Man cannot discover what is good for him to do (7:1–8:17)

- B: Man does not know what will come after him (9:1–11:6)

- Concluding poem (11:7–12:8)

- Epilogue (12:9–14)

Despite the acceptance by some of this structure, there have been many scathing criticisms, such as that of Fox: "[Addison G. Wright's] proposed structure has no more effect on interpretation than a ghost in the attic. A literary or rhetorical structure should not merely 'be there'; it must do something. It should guide readers in recognizing and remembering the author's train of thought." [11]

Verse 1:1 is a superscription, the ancient equivalent of a title page: it introduces the book as "the words of Kohelet, son of David, king in Jerusalem."[12]

Most, though not all, modern commentators regard the epilogue (12:9–14) as an addition by a later scribe. Some have identified certain other statements as further additions intended to make the book more religiously orthodox (e.g., the affirmations of God's justice and the need for piety).[13]

Summary[edit]

The ten-verse introduction in verses 1:2–11 are the words of the frame narrator; they set the mood for what is to follow. Kohelet's message is that all is meaningless.[12]

After the introduction come the words of Kohelet. As king he has experienced everything and done everything, but nothing is ultimately reliable. Death levels all. The only good is to partake of life in the present, for enjoyment is from the hand of God. Everything is ordered in time and people are subject to time in contrast to God's eternal character. The world is filled with injustice, which only God will adjudicate. God and humans do not belong in the same realm and it is therefore necessary to have a right attitude before God. People should enjoy, but should not be greedy; no-one knows what is good for humanity; righteousness and wisdom escape us. Kohelet reflects on the limits of human power: all people face death, and death is better than life, but we should enjoy life when we can. The world is full of risk: he gives advice on living with risk, both political and economic. Mortals should take pleasure when they can, for a time may come when no one can. Kohelet's words finish with imagery of nature languishing and humanity marching to the grave.[14]

The frame narrator returns with an epilogue: the words of the wise are hard, but they are applied as the shepherd applies goads and pricks to his flock. The ending of the book sums up its message: "Fear God and keep his commandments for God will bring every deed to judgement."[15] Apparently, 12:13-14 were an addition by a more orthodox author than the original writer.[16]

Composition[edit]

Title, date and author[edit]

The book takes its name from the Greek ekklesiastes, a translation of the title by which the central figure refers to himself: Kohelet, meaning something like "one who convenes or addresses an assembly".[17] According to rabbinic tradition, Ecclesiastes was written by Solomon in his old age[18] (an alternative tradition that "Hezekiah and his colleagues wrote Isaiah, Proverbs, the Song of Songs and Ecclesiastes" probably means simply that the book was edited under Hezekiah),[19] but critical scholars have long rejected the idea of a pre-exilic origin.[20][21] The presence of Persian loan-words and Aramaisms points to a date no earlier than about 450 BCE,[8] while the latest possible date for its composition is 180 BCE, when the Jewish writer Ben Sira quotes from it.[22] The dispute as to whether Ecclesiastes belongs to the Persian or the Hellenistic periods (i.e., the earlier or later part of this period) revolves around the degree of Hellenization (influence of Greek culture and thought) present in the book. Scholars arguing for a Persian date (c. 450–330 BCE) hold that there is a complete lack of Greek influence;[8] those who argue for a Hellenistic date (c. 330–180 BCE) argue that it shows internal evidence of Greek thought and social setting.[23]

Also unresolved is whether the author and narrator of Kohelet are one and the same person. Ecclesiastes regularly switches between third-person quotations of Kohelet and first-person reflections on Kohelet's words, which would indicate the book was written as a commentary on Kohelet's parables rather than a personally-authored repository of his sayings. Some scholars have argued that the third-person narrative structure is an artificial literary device along the lines of Uncle Remus, although the description of the Kohelet in 12:8–14 seems to favour a historical person whose thoughts are presented by the narrator.[24] The question, however, has no theological importance,[24] and one scholar (Roland Murphy) has commented that Kohelet himself would have regarded the time and ingenuity put into interpreting his book as "one more example of the futility of human effort".[25]

Genre and setting[edit]

Ecclesiastes has taken its literary form from the Middle Eastern tradition of the fictional autobiography, in which a character, often a king, relates his experiences and draws lessons from them, often self-critical: Kohelet likewise identifies himself as a king, speaks of his search for wisdom, relates his conclusions, and recognises his limitations.[9] It belongs to the category of wisdom literature, the body of biblical writings which give advice on life, together with reflections on its problems and meanings—other examples include the Book of Job, Proverbs, and some of the Psalms. Ecclesiastes differs from the other biblical Wisdom books in being deeply skeptical of the usefulness of Wisdom itself.[26] Ecclesiastes in turn influenced the deuterocanonical works, Wisdom of Solomon and Sirach, both of which contain vocal rejections of the Ecclesiastical philosophy of futility.

Wisdom was a popular genre in the ancient world, where it was cultivated in scribal circles and directed towards young men who would take up careers in high officialdom and royal courts; there is strong evidence that some of these books, or at least sayings and teachings, were translated into Hebrew and influenced the Book of Proverbs, and the author of Ecclesiastes was probably familiar with examples from Egypt and Mesopotamia.[27] He may also have been influenced by Greek philosophy, specifically the schools of Stoicism, which held that all things are fated, and Epicureanism, which held that happiness was best pursued through the quiet cultivation of life's simpler pleasures.[28]

Canonicity[edit]

The presence of Ecclesiastes in the Bible is something of a puzzle, as the common themes of the Hebrew canon—a God who reveals and redeems, who elects and cares for a chosen people—are absent from it, which suggests that Kohelet had lost his faith in his old age. Understanding the book was a topic of the earliest recorded discussions (the hypothetical Council of Jamnia in the 1st century CE). One argument advanced at that time was that the name of Solomon carried enough authority to ensure its inclusion; however, other works which appeared with Solomon's name were excluded despite being more orthodox than Ecclesiastes.[29] Another was that the words of the epilogue, in which the reader is told to fear God and keep his commands, made it orthodox; but all later attempts to find anything in the rest of the book that would reflect this orthodoxy have failed. A modern suggestion treats the book as a dialogue in which different statements belong to different voices, with Kohelet himself answering and refuting unorthodox opinions, but there are no explicit markers for this in the book, as there are (for example) in the Book of Job. Yet another suggestion is that Ecclesiastes is simply the most extreme example of a tradition of skepticism, but none of the proposed examples match Ecclesiastes for a sustained denial of faith and doubt in the goodness of God. "In short, we do not know why or how this book found its way into such esteemed company", summarizes Martin A. Shields in his 2006 book The End of Wisdom: A Reappraisal of the Historical and Canonical Function of Ecclesiastes.[30]

Themes[edit]

Scholars disagree about the themes of Ecclesiastes: whether it is positive and life-affirming, or deeply pessimistic;[31] whether it is coherent or incoherent, insightful or confused, orthodox or heterodox; whether the ultimate message of the book is to copy Kohelet, the wise man, or to avoid his errors.[32] At times Kohelet raises deep questions; he "doubted every aspect of religion, from the very ideal of righteousness, to the by now traditional idea of divine justice for individuals".[33] Some passages of Ecclesiastes seem to contradict other portions of the Old Testament, and even itself.[31] The Talmud even suggests that the rabbis considered censoring Ecclesiastes due to its seeming contradictions.[34] One suggestion for resolving the contradictions is to read the book as the record of Kohelet's quest for knowledge: opposing judgments (e.g., "the dead are better off than the living" (4:2) vs. "a living dog is better off than a dead lion" (9:4)) are therefore provisional, and it is only at the conclusion that the verdict is delivered (11–12:7). On this reading, Kohelet's sayings are goads, designed to provoke dialogue and reflection in his readers, rather than to reach premature and self-assured conclusions.[35]

The subjects of Ecclesiastes are the pain and frustration engendered by observing and meditating on the distortions and inequities pervading the world, the uselessness of human deeds, and the limitations of wisdom and righteousness. The phrase "under the sun" appears thirty times in connection with these observations; all this coexists with a firm belief in God, whose power, justice and unpredictability are sovereign.[36] History and nature move in cycles, so that all events are predetermined and unchangeable, and life has no meaning or purpose: the wise man and the man who does not study wisdom will both die and be forgotten: man should be reverent ("Fear God"), but in this life it is best to simply enjoy God's gifts.[28]

Judaism[edit]

In Judaism, Ecclesiastes is read either on Shemini Atzeret (by Yemenites, Italians, some Sepharadim, and the mediaeval French Jewish rite) or on the Shabbat of the Intermediate Days of Sukkot (by Ashkenazim). If there is no Intermediate Sabbath of Sukkot, Ashkenazim too read it on Shemini Atzeret (or, in Israel, on the first Shabbat of Sukkot). It is read on Sukkot as a reminder not to get too caught up in the festivities of the holiday, and to carry over the happiness of Sukkot to the rest of the year by telling the listeners that, without God, life is meaningless.

The final poem of Kohelet (Ecclesiastes 12:1–8) has been interpreted in the Targum, Talmud and Midrash, and by the rabbis Rashi, Rashbam and ibn Ezra, as an allegory of old age.

Catholicism[edit]

Ecclesiastes has been cited in the writings of past and current Catholic Church leaders. For example, doctors of the Church have cited Ecclesiastes. St. Augustine of Hippo cited Ecclesiastes in Book XX of City of God.[37]Saint Jerome wrote a commentary on Ecclesiastes.[38]St. Thomas Aquinas cited Ecclesiastes ("The number of fools is infinite.") in his Summa Theologica.[39]

The twentieth-century Catholic theologian and cardinal-elect Hans Urs von Balthasar discusses Ecclesiastes in his work on theological aesthetics, The Glory of the Lord. He describes Qoheleth as "a critical transcendentalistavant la lettre", whose God is distant from the world, and whose kairos is a "form of time which is itself empty of meaning". For Balthasar, the role of Ecclesiastes in the Biblical canon is to represent the "final dance on the part of wisdom, [the] conclusion of the ways of man", a logical end-point to the unfolding of human wisdom in the Old Testament that paves the way for the advent of the New.[40]

The book continues to be cited by recent popes, including Pope John Paul II and Pope Francis. Pope John Paul II, in his general audience of October 20, 2004, called the author of Ecclesiastes "an ancient biblical sage" whose description of death "makes frantic clinging to earthly things completely pointless."[41] Pope Francis cited Ecclesiastes on his address on September 9, 2014. Speaking of vain people, he said, "How many Christians live for appearances? Their life seems like a soap bubble."[42]

Influence on Western literature[edit]

Ecclesiastes has had a deep influence on Western literature. It contains several phrases that have resonated in British and American culture, such as "eat, drink and be merry", "nothing new under the sun", "a time to be born and a time to die", and "vanity of vanities; all is vanity".[43] American novelist Thomas Wolfe wrote: "[O]f all I have ever seen or learned, that book seems to me the noblest, the wisest, and the most powerful expression of man's life upon this earth—and also the highest flower of poetry, eloquence, and truth. I am not given to dogmatic judgments in the matter of literary creation, but if I had to make one I could say that Ecclesiastes is the greatest single piece of writing I have ever known, and the wisdom expressed in it the most lasting and profound."[44]

- Abraham Lincoln quoted Ecclesiastes 1:4 in his address to the reconvening Congress on December 1, 1862, during the darkest hours of the American Civil War: "'One generation passeth away, and another generation cometh: but the earth abideth for ever.' ... Our strife pertains to ourselves—to the passing generations of men; and it can without convulsion be hushed forever with the passing of one generation."[45]

- The opening of William Shakespeare's Sonnet 59 references Ecclesiastes 1:9–10.

- Line 23 of T. S. Eliot's "The Waste Land" alludes to Ecclesiastes 12:5.

- Leo Tolstoy's Confession describes how the reading of Ecclesiastes affected his life.

- Robert Burns' "Address to the Unco Guid" begins with a verse appeal to Ecclesiastes 7:16.

- The title of Ernest Hemingway's first novel The Sun Also Rises comes from Ecclesiastes 1:5.

- The title of Edith Wharton's novel The House of Mirth was taken from Ecclesiastes 7:4 ("The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning; but the heart of fools is in the house of mirth.").

- The title of Laura Lippman's novel Every Secret Thing and that of its film adaptation come from Ecclesiastes 12:14 ("For God shall bring every work into judgment, with every secret thing, whether it be good, or whether it be evil.").

- The main character in George Bernard Shaw's short story The Adventures of the Black Girl in Her Search for God[46] meets Koheleth, "known to many as Ecclesiastes".

- The title and theme of George R. Stewart's post-apocalyptic novel Earth Abides is from Ecclesiastes 1:4.

- In the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451, Ray Bradbury's main character, Montag, memorizes much of Ecclesiastes and Revelation in a world where books are forbidden and burned.

- Pete Seeger's song "Turn! Turn! Turn!" takes all but one of its lines from the Book of Ecclesiastes chapter 3.

See also[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^Weeks 2007, pp. 428–429.

- ^"Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^"Strong's Hebrew: 6951. קָהָל (qahal) -- assembly, convocation, congregation". biblehub.com. Retrieved 2020-07-29.

- ^"Greek Word Study Tool". www.perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^ abEven-Shoshan, Avraham (2003). Even-Shoshan Dictionary. pp. Entry "קֹהֶלֶת".

- ^ ab"H6953 קהלת - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon". studybible.info. Retrieved 2020-07-28.

- ^as opposed to the Hifil form, always active 'to assemble', and niphal form, always passive 'to be assembled' -- both forms often used in the Bible.

- ^ abcSeow 2007, p. 944.

- ^ abFox 2004, p. xiii.

- ^Fox 2004, p. xvi.

- ^Fox 2004, p. 148-149.

- ^ abLongman 1998, pp. 57–59.

- ^Fox 2004, p. xvii.

- ^Seow 2007, pp. 946–57.

- ^Seow 2007, pp. 957–58.

- ^Ross, Allen P.; Shepherd, Jerry E.; Schwab, George (7 March 2017). Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs. Zondervan Academic. p. 448. ISBN .

- ^Gilbert 2009, pp. 124–25.

- ^Brown 2011, p. 11.

- ^Smith 2007, p. 692. sfn error: no target: CITEREFSmith2007 (help)

- ^Fox 2004, p. x.

- ^Bartholomew 2009, pp. 50–52.

- ^Fox 2004, p. xiv.

- ^Bartholomew 2009, pp. 54–55.

- ^ abBartholomew 2009, p. 48.

- ^Ingram 2006, p. 45.

- ^Brettler 2007, p. 721.

- ^Fox 2004, pp. x–xi.

- ^ abGilbert 2009, p. 125.

- ^Diderot, Denis (1752). "Canon". Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert - Collaborative Translation Project: 601–04. hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.566.

- ^Shields 2006, pp. 1-5.

- ^ abBartholomew 2009, p. 17.

- ^Enns 2011, p. 21.

- ^Hecht, Jennifer Michael (2003). Doubt: A History. New York: HarperCollins. pp. 75. ISBN .

- ^Babylonian Talmud Shabbat 30b. sfn error: no target: CITEREFBabylonian_Talmud_Shabbat_30b (help)

- ^Brown 2011, pp. 17–18.

- ^Fox 2004, p. ix.

- ^Augustine. "Book XX". The City of God.

- ^Jerome. Commentary on Ecclesiastes.

- ^Thomas Aquinas. Summa Theologica.

- ^von Balthasar, Hans Urs (1991). The Glory of the Lord. Volume VI: Theology: The Old Covenant. Translated by Brian McNeil and Erasmo Leiva-Merikakis. Edinburgh: T&T Clark. pp. 137–43.

- ^Manhardt, Laurie (2009). Come and See: Wisdom of the Bible. Emmaus Road Publishing. p. 115. ISBN .

- ^Pope Francis. "Pope Francis: Vain Christians are like soap bubbles". Radio Vatican. Retrieved 2015-09-09.

- ^Hirsch, E.D. (2002). The New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 8. ISBN .

- ^Christianson 2007, p. 70.

- ^Foote, Shelby (1986). The Civil War, a narrative, vol. 1. Vintage Books. pp. 807–08. ISBN .

- ^Shaw, Bernard (2006). The adventures of the black girl in her search for God. London: Hesperus. ISBN . OCLC 65469757.

References[edit]

- Bartholomew, Craig G. (2009). Ecclesiastes. Baker Academic. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brettler, Mark Zvi (2007). "The Poetical and Wisdom Books". In Coogan, Michael D. (ed.). The New Oxford Annotated Bible (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brown, William P. (2011). Ecclesiastes: Interpretation: A Bible Commentary for Teaching and Preaching. Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Christianson, Eric S. (2007). Ecclesiastes Through the Centuries. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Coogan, Michael D. (2008). The Old Testament: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Diderot, Denis (1752). "Canon". The Encyclopedia of Diderot & d'Alembert Collaborative Translation Project. Translated by Susan Emanuel (2006). hdl:2027/spo.did2222.0000.566.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) Trans. of "Canon", Encyclopédie ou Dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, vol. 2. Paris, 1752.

- Eaton, Michael (2009). Ecclesiastes: An Introduction and Commentary. IVP Academic. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2013-01-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Enns, Peter (2011). Ecclesiastes. Eerdmans. ISBN .CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fredericks, Daniel C.; Estes, Daniel J. (2010). Ecclesiastes & the Song of Songs. IVP Academic. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2013-01-07.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

How to run No One Lives Forever 2 on Windows 7/8

Twice a month, Pixel Boost guides you through the hacks, tricks, and mods you'll need to run a classic PC game on Windows 7/8. Each guide comes with a free side of 4K screenshots from the LPC celebrating the graphics of PC gaming's past. This week: Cate Archer lives forever (in our hearts).

It's been 12 years since the PC hosted the adventures of 1960s superspy Cate Archer. Twelve years too long. If you've played NOLF or its sequel, No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way, you know why they're some of the best shooters of all time : smart AI, inventive weaponry, and an endlessly witty script. They were also some of the best-looking games of the early 2000s, which means they hold up remarkably well today--with a little tinkering to add widescreen support and higher resolutions. While the rights to the NOLF games have been lost to legal limbo for years, a trademark filing back in May could hint that they'll finally show up on Steam or GOG in the future. For now, the only way to play them is to load up a trusty old CD copy. If you've got one, it's time to put on your best spy outfit and get ready to Pixel Boost.

Install it

As mentioned above, there's currently no easy way to get ahold of No One Lives Forever or NOLF2. Developer Monolith Productions was acquired in 2004, and publisher Sierra was absorbed into Activision in 2008. On the bright side, disc copies aren't too rare. You can grab one on eBay for about $10-$20 (£5-10 in the UK) , or even pick up a brand new copy on Amazon for $20.

No One Lives Forever 2 installs just fine on Windows 7 and Windows 8.1, but the first game requires a special patched installer for 64-bit Windows. You can grab that installer on Play Old PC Games.

Run it in high resolution

There are two simple steps to running No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way at a decent resolution on modern Windows.

Step one: patch the game. When you install NOLF 2 from its CDs, it'll be running version 1.0, not the final 1.3. The game's built-in patcher is no good, since Sierra's servers shut off years ago. Thankfully, patch 1.3 is easy to find online. Download it from ModDB and install it.

Step two: add widescreen support. A Widescreen Gaming Forum member created a simple patch for the game that adds widescreen support and makes it easy to adjust FOV and resolution. Download the patch here and follow its simple instructions to get it running.

The patch works almost perfectly. When Cate takes damage, you'll notice the flash of red that appears on the screen (as you can see in one of the screens on the next page) is still 4:3. Some text in the menus isn't quite properly aligned. But the game perfectly playable in widescreen, and I was able to run it at 1440p with no issues. Unfortunately, NOLF 2 crashed when I tried to run it at resolutions above 1440p, and I couldn't figure out why.

Mod it

NOLF2 doesn't have an active modding scene, but there are two mods to check out if you're a dedicated fan. The first is LiveForever Mod , which will allow you to play multiplayer online even though Sierra's servers have long gone silent.

The second is the No One Lives Forever 2 toolkit , which provides editing tools and the game's source code. Write your own mods!

No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way at 2560x1440 on the LPC

These screenshots were taken on the Large Pixel Collider, with No One Lives Forever 2: A Spy in H.A.R.M.'s Way running at 1440p with all settings cranked to the max.

Current page: Page 1

Next PagePage 2

God Creates and Equips People to Work (Genesis 1:26-2:25)

People are Created in God’s Image (Genesis 1:26, 27; 5:1)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsHaving told the story of God’s work of creation, Genesis moves on to tell the story of human work. Everything is grounded on God’s creation of people in his own image.

God said, “Let us make humankind in our image, according to our likeness.” (Gen. 1:26)

So God created humankind in his image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them. (Gen. 1:27)

When God created humankind, he made them in the likeness of God. (Gen. 5:1)

All creation displays God’s design, power, and goodness, but only human beings are said to be made in God’s image. A full theology of the image of God is beyond our scope here, so let us simply note that something about us is uniquely like him. It would be ridiculous to believe that we are exactly like God. We can’t create worlds out of pure chaos, and we shouldn’t try to do everything God does. "Beloved, never avenge yourselves, but leave room for the wrath of God; for it is written, ‘Vengeance is mine, I will repay, says the Lord’ " (Rom. 12:19). But the chief thing we know about God, so far in the narrative, is that God is a creator who works in the material world, who works in relationship, and whose work observes limits. We have the ability to do the same.

The rest of Genesis 1 and 2 develops human work in five specific categories: dominion, relationships, fruitfulness/growth, provision, and limits. The development occurs in two cycles, one in Genesis 1:26-2:4 and the other in Genesis 2:4-25. The order of the categories is not exactly in the same order both times, but all the categories are present in both cycles. The first cycle develops what it means to work in God’s image. The second cycle describes how God equips Adam and Eve for their work as they begin life in the Garden of Eden.

The language in the first cycle is more abstract and therefore well-suited for developing principles of human labor. The language in the second cycle is earthier, speaking of God forming things out of dirt and other elements, and is well suited for practical instruction for Adam and Eve in their particular work in the garden. This shift of language—with similar shifts throughout the first four books of the Bible—has attracted uncounted volumes of research, hypothesis, debate, and even division among scholars. Any general purpose commentary will provide a wealth of details. Most of these debates, however, have little impact on what the book of Genesis contributes to understanding work, workers, and workplaces, and we will not attempt to take a position on them here. What is relevant to our discussion is that chapter 2 repeats five themes developed earlier—in the order of dominion, provision, fruitfulness/growth, limits, and relationships—by describing how God equips people to fulfill the work we are created to do in his image. In order to make it easier to follow these themes, we will explore Genesis 1:26-2:25 category by category, rather than verse by verse. The following table gives a convenient index (with links) for those interested in exploring a particular verse immediately.

Dominion (Genesis 1:26; 2:5)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsTo work in God’s image is to exercise dominion (Genesis 1:26)

A consequence we see in Genesis of being created in God’s image is that we are to “have dominion over the fish of the sea, and over the birds of the air, and over the cattle, and over all the wild animals of the earth, and over every creeping thing that creeps upon the earth” (Gen. 1:26). As Ian Hart puts it, "Exercising royal dominion over the earth as God's representative is the basic purpose for which God created man.... Man is appointed king over creation, responsible to God the ultimate king, and as such expected to manage and develop and care for creation, this task to include actual physical work."[1] Our work in God’s image begins with faithfully representing God.

As we exercise dominion over the created world, we do it knowing that we mirror God. We are not the originals but the images, and our duty is to use the original—God—as our pattern, not ourselves. Our work is meant to serve God’s purposes more than our own, which prevents us from domineering all that God has put under our control.

Think about the implications of this in our workplaces. How would God go about doing our job? What values would God bring to it? What products would God make? Which people would God serve? What organizations would God build? What standards would God use? In what ways, as image-bearers of God, should our work display the God we represent? When we finish a job, are the results such that we can say, “Thank you, God, for using me to accomplish this?”

God equips people for the work of dominion (Genesis 2:5)

The cycle begins again with dominion, although it may not be immediately recognizable as such. "No plant of the field was yet in the earth and no herb of the field had yet sprung up—for the Lord God had not caused it to rain upon the earth, and there was no one to till the ground" (Gen. 2:5; emphasis added). The key phrase is “there was no one to till the ground.” God chose not to bring his creation to a close until he created people to work with (or under) him. Meredith Kline puts it this way, "God's making the world was like a king's planting a farm or park or orchard, into which God put humanity to 'serve' the ground and to 'serve' and 'look after' the estate."[2]

Thus the work of exercising dominion begins with tilling the ground. From this we see that God's use of the words subdue[3] and dominion in chapter 1 do not give us permission to run roughshod over any part of his creation. Quite the opposite. We are to act as if we ourselves had the same relationship of love with his creatures that God does. Subduing the earth includes harnessing its various resources as well as protecting them. Dominion over all living creatures is not a license to abuse them, but a contract from God to care for them. We are to serve the best interests of all whose lives touch ours; our employers, our customers, our colleagues or fellow workers, or those who work for us or who we meet even casually. That does not mean that we will allow people to run over us, but it does mean that we will not allow our self-interest, our self-esteem, or our self-aggrandizement to give us a license to run over others. The later unfolding story in Genesis focuses attention on precisely that temptation and its consequences.

Today we have become especially aware of how the pursuit of human self-interest threatens the natural environment. We were meant to tend and care for the garden (Gen. 2:15). Creation is meant for our use, but not only for our use. Remembering that the air, water, land, plants, and animals are good (Gen. 1:4-31) reminds us that we are meant to sustain and preserve the environment. Our work can either preserve or destroy the clean air, water, and land, the biodiversity, the ecosystems, and biomes, and even the climate with which God has blessed his creation. Dominion is not the authority to work against God’s creation, but the ability to work for it.

Relationships and Work (Genesis 1:27; 2:18, 21-25)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsTo Work in God’s Image Is to Work in Relationship with Others (Genesis 1:27)

A consequence we see in Genesis of being created in God’s image is that we work in relationship with God and one another. We have already seen that God is inherently relational (Gen. 1:26), so as images of a relational God, we are inherently relational. The second part of Genesis 1:27 makes the point again, for it speaks of us not individually but in twos, “Male and female he created them.” We are in relationship with our creator and with our fellow creatures. These relationships are not left as philosophical abstractions in Genesis. We see God talking and working with Adam in naming the animals (Gen. 2:19). We see God visiting Adam and Eve “in the garden at the time of the evening breeze” (Gen. 3:8).

How does this reality impact us in our places of work? Above all, we are called to love the people we work with, among, and for. The God of relationship is the God of love (1 John 4:7). One could merely say that "God loves," but Scripture goes deeper to the very core of God's being as Love, a love flowing back and forth among the Father, the Son (John 17:24), and the Holy Spirit. This love also flows out of God's being to us, doing nothing that is not in our best interest (agape love in contrast to human loves situated in our emotions).

Francis Schaeffer explores further the idea that because we are made in God's image and because God is personal, we can have a personal relationship with God. He notes that this makes genuine love possible, stating that machines can't love. As a result, we have a responsibility to care consciously for all that God has put in our care. Being a relational creature carries moral responsibility.[1]

God Equips People to Work in Relationship with Others (Genesis 2:18, 21-25)

Because we are made in the image of a relational God, we are inherently relational ourselves. We are made for relationships with God himself and also with other people. God says, “It is not good that the man should be alone; I will make him a helper as his partner” (Gen. 2:18). All of his creative acts had been called "good" or "very good," and this is the first time that God pronounces something "not good." So God makes a woman out of the flesh and bone of Adam himself. When Eve arrives, Adam is filled with joy. “This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh” (Gen. 2:23). (After this one instance, all new people will continue to come out of the flesh of other human beings, but born by women rather than men.) Adam and Eve embark on a relationship so close that “they become one flesh” (Gen. 1:24). Although this may sound like a purely erotic or family matter, it is also a working relationship. Eve is created as Adam’s “helper” and “partner” who will join him in working the Garden of Eden. The word helper indicates that, like Adam, she will be tending the garden. To be a helper means to work. Someone who is not working is not helping. To be a partner means to work with someone, in relationship.

When God calls Eve a “helper,” he is not saying she will be Adam’s inferior or that her work will be less important, less creative, less anything, than his. The word translated as “helper” here (Hebrew ezer) is a word used elsewhere in the Old Testament to refer to God himself. “God is my helper [ezer]” (Psalm 54:4). “Lord, be my helper [ezer]” (Ps. 30:10). Clearly, an ezer is not a subordinate. Moreover, Genesis 2:18 describes Eve not only as a “helper” but also as a “partner.” The English word most often used today for someone who is both a helper and a partner is “co-worker.” This is indeed the sense already given in Genesis 1:27, “male and female he created them,” which makes no distinction of priority or dominance. Domination of women by men—or vice versa—is not in accordance with God’s good creation. It is a tragic consequence of the Fall (Gen. 3:16).

Relationships are not incidental to work; they are essential. Work serves as a place of deep and meaningful relationships, under the proper conditions at least. Jesus described our relationship with himself as a kind of work, “Take my yoke upon you, and learn from me; for I am gentle and humble in heart, and you will find rest for your souls” (Matt. 11:29). A yoke is what makes it possible for two oxen to work together. In Christ, people may truly work together as God intended when he made Eve and Adam as co-workers. While our minds and bodies work in relationship with other people and God, our souls “find rest.” When we don’t work with others towards a common goal, we become spiritually restless. For more on yoking, see the section on 2 Corinthians 6:14-18 in the Theology of Work Commentary.

A crucial aspect of relationship modeled by God himself is delegation of authority. God delegated the naming of the animals to Adam, and the transfer of authority was genuine. “Whatever the man called every living creature, that was its name” (Gen. 2:19). In delegation, as in any other form of relationship, we give up some measure of our power and independence and take the risk of letting others’ work affect us. Much of the past fifty years of development in the fields of leadership and management has come in the form of delegating authority, empowering workers, and fostering teamwork. The foundation of this kind of development has been in Genesis all along, though Christians have not always noticed it.

Can You Love Your Employees?(Click Here to Read)Samantha thought the advice of her grad school professor was a little unusual—words given her as she was about to launch her career: “Don’t get too close to your co-workers,” he said. “You never know when you’re going to have to fire someone, and you don’t want to fire your close friends.” |

Many people form their closest relationships when some kind of work—whether paid or not—provides a common purpose and goal. In turn, working relationships make it possible to create the vast, complex array of goods and services beyond the capacity of any individual to produce. Without relationships at work, there are no automobiles, no computers, no postal services, no legislatures, no stores, no schools, no hunting for game larger than one person can bring down. And without the intimate relationship between a man and a woman, there are no future people to do the work God gives. Our work and our community are thoroughly intertwined gifts from God. Together they provide the means for us to be fruitful and multiply in every sense of the words.

Fruitfulness/Growth (Genesis 1:28; 2:15, 19-20)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsTo work in God’s image is to bear fruit and multiply (Genesis 1:28)

Since we are created in God’s image, we are to be fruitful, or creative. This is often called the “creation mandate” or “cultural mandate.” God brought into being a flawless creation, an ideal platform, and then created humanity to continue the creation project. “God blessed them, and God said to them, ‘Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth’ ” (Gen. 1:28a). God could have created everything imaginable and filled the earth himself. But he chose to create humanity to work alongside him to actualize the universe’s potential, to participate in God’s own work. It is remarkable that God trusts us to carry out this amazing task of building on the good earth he has given us. Through our work God brings forth food and drink, products and services, knowledge and beauty, organizations and communities, growth and health, and praise and glory to himself.

A word about beauty is in order. God’s work is not only productive, but it is also a “delight to the eyes” (Gen. 3:6). This is not surprising, since people, being in the image of God, are inherently beautiful. Like any other good, beauty can become an idol, but Christians have often been too worried about the dangers of beauty and too unappreciative of beauty’s value in God’s eyes. Inherently, beauty is not a waste of resources, or a distraction from more important work, or a flower doomed to fade away at the end of the age. Beauty is a work in the image of God, and the kingdom of God is filled with beauty “like a very rare jewel” (Rev. 21:11). Christian communities do well at appreciating the beauty of music with words about Jesus. Perhaps we could do better at valuing all kinds of true beauty.

A good question to ask ourselves is whether we are working more productively and beautifully. History is full of examples of people whose Christian faith resulted in amazing accomplishments. If our work feels fruitless next to theirs, the answer lies not in self-judgment, but in hope, prayer, and growth in the company of the people of God. No matter what barriers we face—from within or without—by the power of God we can do more good than we could ever imagine.

God equips people to bear fruit and multiply (Genesis 2:15, 19-20)

"The Lord God took the man and put him in the Garden of Eden to till it and keep it" (Gen. 2:15). These two words in Hebrew, avad (“work” or “till”) and shamar (“keep”), are also used for the worship of God and keeping his commandments, respectively.[1] Work done according to God’s purpose has an unmistakable holiness.

Adam and Eve are given two specific kinds of work in Genesis 2:15-20, gardening (a kind of physical work) and giving names to the animals (a kind of cultural/scientific/intellectual work). Both are creative enterprises that give specific activities to people created in the image of the Creator. By growing things and developing culture, we are indeed fruitful. We bring forth the resources needed to support a growing population and to increase the productivity of creation. We develop the means to fill, yet not overfill, the earth. We need not imagine that gardening and naming animals are the only tasks suitable for human beings. Rather the human task is to extend the creative work of God in a multitude of ways limited only by God’s gifts of imagination and skill, and the limits God sets. Work is forever rooted in God's design for human life. It is an avenue to contribute to the common good and as a means of providing for ourselves, our families, and those we can bless with our generosity.

An important (though sometimes overlooked) aspect of God at work in creation is the vast imagination that could create everything from exotic sea life to elephants and rhinoceroses. While theologians have created varying lists of those characteristics of God that have been given to us that bear the divine image, imagination is surely a gift from God we see at work all around us in our workspaces as well as in our homes.

Much of the work we do uses our imagination in some way. We tighten bolts on an assembly line truck and we imagine that truck out on the open road. We open a document on our laptop and imagine the story we're about to write. Mozart imagined a sonata and Beethoven imagined a symphony. Picasso imagined Guernica before picking up his brushes to work on that painting. Tesla and Edison imagined harnessing electricity, and today we have light in the darkness and myriad appliances, electronics, and equipment. Someone somewhere imagined virtually everything surrounding us. Most of the jobs people hold exist because someone could imagine a job-creating product or process in the workplace.

Yet imagination takes work to realize, and after imagination comes the work of bringing the product into being. Actually, in practice the imagination and the realization often occur in intertwined processes. Picasso said of his Guernica, "A painting is not thought out and settled in advance. While it is being done, it changes as one's thoughts change. And when it's finished, it goes on changing, according to the state of mind of whoever is looking at it."[2] The work of bringing imagination into reality brings its own inescapable creativity.

Provision (Genesis 1:29-30; 2:8-14)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsTo Work in God’s Image Is to Receive God’s Provision (Genesis 1:29-30)

Since we are created in God's image, God provides for our needs. This is one of the ways in which those made in God’s image are not God himself. God has no needs, or if he does he has the power to meet them all on his own. We don’t. Therefore:

God said, "See, I have given you every plant yielding seed that is upon the face of all the earth, and every tree with seed in its fruit; you shall have them for food. And to every beast of the earth, and to every bird of the air, and to everything that creeps on the earth, everything that has the breath of life, I have given every green plant for food.” And it was so. (Gen. 1:29-30)

On the one hand, acknowledging God’s provision warns us not to fall into hubris. Without him, our work is nothing. We cannot bring ourselves to life. We cannot even provide for our own maintenance. We need God’s continuing provision of air, water, earth, sunshine, and the miraculous growth of living things for food for our bodies and minds. On the other hand, acknowledging God’s provision gives us confidence in our work. We do not have to depend on our own ability or on the vagaries of circumstance to meet our need. God’s power makes our work fruitful.

God Equips People with Provision for Their Needs (Genesis 2:8-14)

The second cycle of the creation account shows us something of how God provides for our needs. He prepares the earth to be productive when we apply our work to it. “The Lord God planted a garden in Eden, in the east; and there he put the man whom he had formed" (Gen. 2:8). Though we till, God is the original planter. In addition to food, God has created the earth with resources to support everything we need to be fruitful and multiply. He gives us a multitude of rivers providing water, ores yielding stone and metal materials, and precursors to the means of economic exchange (Gen. 2:10-14). “There is gold, and the gold of that land is good” (Gen. 2:11-12). Even when we synthesize new elements and molecules or when we reshuffle DNA among organisms or create artificial cells, we are working with the matter and energy that God brought into being for us.

God Sets Limits (Genesis 2:3; 2:17)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsTo Work in God’s Image Is to Be Blessed by the Limits God Sets (Genesis 2:3)

Since we are created in God’s image, we are to obey limits in our work. "God blessed the seventh day and hallowed it, because on it God rested from all the work that he had done in creation" (Genesis 2:3). Did God rest because he was exhausted, or did he rest to offer us image-bearers a model cycle of work and rest? The fourth of the Ten Commandments tells us that God’s rest is meant as an example for us to follow.

Remember the sabbath day, and keep it holy. Six days you shall labor and do all your work. But the seventh day is a sabbath to the Lord your God; you shall not do any work—you, your son or your daughter, your male or female slave, your livestock, or the alien resident in your towns. For in six days the Lord made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, but rested the seventh day; therefore the Lord blessed the sabbath day and consecrated it. (Exod. 20:8-11)

While religious people over the centuries tended to pile up regulations defining what constituted keeping the Sabbath, Jesus said clearly that God made the Sabbath for us–for our benefit (Mark 2:27). What are we to learn from this?

Making time off predictable and requiredRead more here about a new study regarding rhythms of rest and work done at the Boston Consulting Group by two professors from Harvard Business School. It showed that when the assumption that everyone needs to be always available was collectively challenged, not only could individuals take time off, but their work actually benefited. (Harvard Business Review may show an ad and require registration in order to view the article.) Mark Roberts also discusses this topic in his Life for Leaders devotional "Won't Keeping the Sabbath Make Me Less Productive?" |

When, like God, we stop our work on whatever is our seventh day, we acknowledge that our life is not defined only by work or productivity. Walter Brueggemann put it this way, "Sabbath provides a visible testimony that God is at the center of life—that human production and consumption take place in a world ordered, blessed, and restrained by the God of all creation."[1] In a sense, we renounce some part of our autonomy, embracing our dependence on God our Creator. Otherwise, we live with the illusion that life is completely under human control. Part of making Sabbath a regular part of our work life acknowledges that God is ultimately at the center of life. (Further discussions of Sabbath, rest, and work can be found in the sections on "Mark 1:21-45," "Mark 2:23-3:6," "Luke 6:1-11," and "Luke 13:10-17" in the Theology of Work Commentary.)

God Equips People to Work within Limits (Genesis 2:17)

Having blessed human beings by his own example of observing workdays and Sabbaths, God equips Adam and Eve with specific instructions about the limits of their work. In the midst of the Garden of Eden, God plants two trees, the tree of life and the tree of the knowledge of good and evil (Gen. 2:9). The latter tree is off limits. God tells Adam, "You may freely eat of every tree of the garden; but of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you shall not eat, for in the day that you eat of it you shall die" (Gen. 2:16-17).

Theologians have speculated at length about why God would put a tree in the Garden of Eden that he didn’t want the inhabitants to use. Various hypotheses are found in the general commentaries, and we need not settle on an answer here. For our purposes, it is enough to observe that not everything that can be done should be done. Human imagination and skill can work with the resources of God’s creation in ways inimical to God’s intents, purposes, and commands. If we want to work with God, rather than against him, we must choose to observe the limits God sets, rather than realizing everything possible in creation.

Francis Schaeffer has pointed out that God didn't give Adam and Eve a choice between a good tree and an evil tree, but a choice whether or not to acquire the knowledge of evil. (They already knew good, of course.) In making that tree, God opened up the possibility of evil, but in doing so God validated choice. All love is bound up in choice; without choice the word love is meaningless.[2] Could Adam and Eve love and trust God sufficiently to obey his command about the tree? God expects that those in relationship with him will be capable of respecting the limits that bring about good in creation.

In today’s places of work, some limits continue to bless us when we observe them. Human creativity, for example, arises as much from limits as from opportunities. Architects find inspiration from the limits of time, money, space, materials, and purpose imposed by the client. Painters find creative expression by accepting the limits of the media with which they choose to work, beginning with the limitations of representing three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional canvas. Writers find brilliance when they face page and word limits.

The Gift of Limits (Click to read)How do you avoid failure? A lot of people come to a crisis in their lives that forces them to recognize their shortcomings. Jim Moats claims, "I believe that failure is the least efficient method for discovering limitations." Instead, he welcomes us to embrace our limitations, thereby allowing ourselves and others around us to flourish.[3] |

All good work respects God’s limits. There are limits to the earth’s capacity for resource extraction, pollution, habitat modification, and the use of plants and animals for food, clothing, and other purposes. The human body has great yet limited strength, endurance, and capacity to work. There are limits to healthy eating and exercise. There are limits by which we distinguish beauty from vulgarity, criticism from abuse, profit from greed, friendship from exploitation, service from slavery, liberty from irresponsibility, and authority from dictatorship. In practice it may be hard to know exactly where the line is, and it must be admitted that Christians have often erred on the side of conformity, legalism, prejudice, and a stifling dreariness, especially when proclaiming what other people should or should not do. Nonetheless, the art of living as God’s image-bearers requires learning to discern where blessings are to be found in observing the limits set by God that are evident in his creation.

The Work of the “Creation Mandate” (Genesis 1:28, 2:15)

Back to Table of ContentsBack to Table of ContentsIn describing God’s creation of humanity in his image (Gen. 1:1-2:3) and equipping of humanity to live according to that image (Gen. 2:4-25), we have explored God’s creation of people to exercise dominion, to be fruitful and multiply, to receive God’s provision, to work in relationships, and to observe the limits of creation. We noted that these have often been called the “creation mandate” or “cultural mandate,” with Genesis 1:28 and 2:15 standing out in particular:

God blessed them, and God said to them, “Be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” (Gen. 1:28)

The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it. (Gen. 2:15)

The use of this terminology is not essential, but the idea it stands for seems clear in Genesis 1 and 2. From the beginning God intended human beings to be his junior partners in the work of bringing his creation to fulfillment. It is not in our nature to be satisfied with things as they are, to receive provision for our needs without working, to endure idleness for long, to toil in a system of uncreative regimentation, or to work in social isolation. To recap, we are created to work as sub-creators in relationship with other people and with God, depending on God’s provision to make our work fruitful and respecting the limits given in his Word and evident in his creation.

Every resource on our site was made possible through the financial support of people like you. With your gift of any size, you’ll enable us to continue equipping Christians with high-quality biblically-based content.

Theology of Work Bible Commentary - One Volume Edition

The Theology of Work Bible Commentary is an in-depth Bible study tool put together by a group of biblical scholars, pastors, and workplace Christians to help you discover what the whole Bible--from Genesis to Revelation--says about work. Business, education, law, service industries, medicine, government--wherever you work, in whatever capacity, the Scriptures have something to say about it. This edition is a one-volume hardcover version.

The Theology of Work Bible Commentary is an in-depth Bible study tool put together by a group of biblical scholars, pastors, and workplace Christians to help you discover what the whole Bible--from Genesis to Revelation--says about work. Business, education, law, service industries, medicine, government--wherever you work, in whatever capacity, the Scriptures have something to say about it. This edition is a one-volume hardcover version.

Buy it now

cover.jpg) Genesis 1-11 Bible Study

Genesis 1-11 Bible Study

While every book of the Bible will contribute something to our understanding of work, Genesis proves to be the fountain from which the Bible's theology of work flows. Great for group or individual use, at home or at work on your lunch break, this study delves into what the story of Creation has to say about faith and work.

Buy it now

Contributors: Andrew Schmutzer and Alice Mathews

Adopted by the Theology of Work Project Board June 11, 2013. Image by Flamingo Images via Shutterstock. Used with Permission.

Theology of Work Project Online Materials by Theology of Work Project, Inc. is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.theologyofwork.org

You are free to share (to copy, distribute and transmit the work), and remix (to adapt the work) for non-commercial use only, under the condition that you must attribute the work to the Theology of Work Project, Inc., but not in any way that suggests that it endorses you or your use of the work.

© 2013 by the Theology of Work Project, Inc.

Unless otherwise noted, the Scripture quotations contained herein are from the New Revised Standard Version Bible, Copyright © 1989, Division of Christian Education of the National Council of the Churches of Christ in the U.S.A., and are used by permission. All rights reserved.

What’s New in the No One Lives Forever 2 Deut. serial key or number?

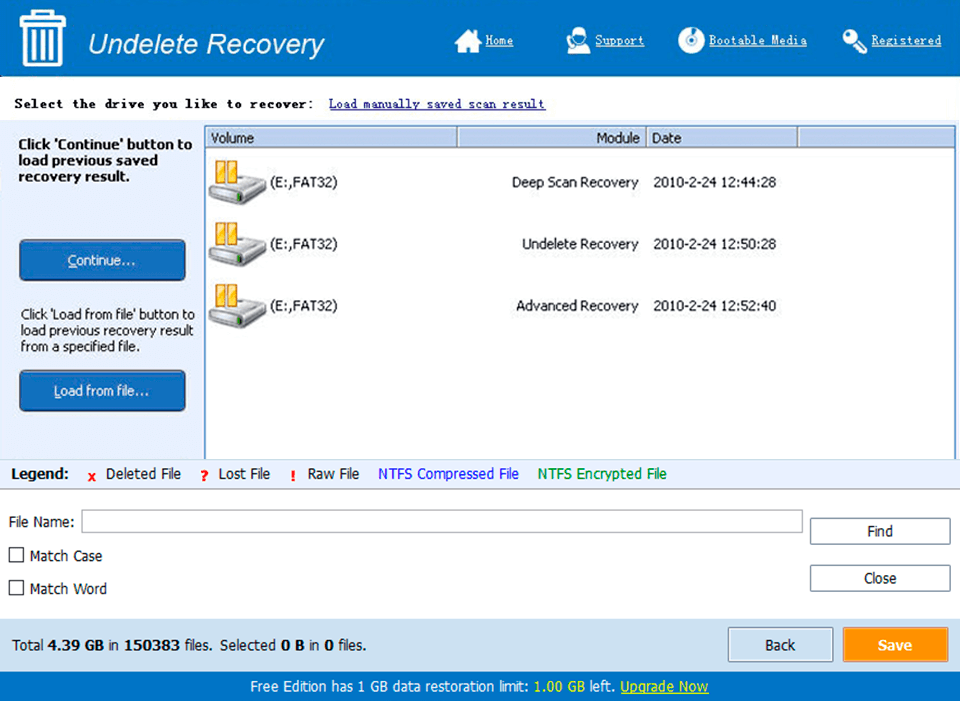

Screen Shot

System Requirements for No One Lives Forever 2 Deut. serial key or number

- First, download the No One Lives Forever 2 Deut. serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: