3D Geometrical Objects v1.3 by REVENGE serial key or number

3D Geometrical Objects v1.3 by REVENGE serial key or number

3ds max pirated

Informed Architecture

This book connects the different topics and professions involved in information technology approaches to architectural design, ranging from computer-aided design, building information modeling and programming to simulation, digital representation, augmented and virtual reality, digital fabrication and physical computation. The contributions include experts’ academic and practical experiences and findings in research and advanced applications, covering the fields of architecture, engineering, design and mathematics.

What are the conditions, constraints and opportunities of this digital revolution for architecture? How do processes change and influence the result? What does it mean for the collaboration and roles of the partners involved. And last but not least: how does academia reflect and shape this development and what does the future hold? Following the sequence of architectural production - from design to fabrication and construction up to the operation of buildings - the book discusses the impact of computational methods and technologies and its consequences for the education of future architects and designers. It offers detailed insights into the processes involved and considers them in the context of our technical, historical, social and cultural environment. Intended mainly for academic researchers, the book is also of interest to master’s level students.Keywords

- Marco Hemmerling

- Luigi Cocchiarella

- 1.Computational Design in Architecture, Faculty of ArchitectureCologne University of Applied SciencesCologneGermany

- 2.Department of Architecture and Urban Studies (DASTU)Politecnico di MilanoMilanItaly

Bibliographic information

Geometry

Geometry (from the Ancient Greek: γεωμετρία; geo- "earth", -metron "measurement") is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space that are related with distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures.[1] A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is called a geometer.

Until the 19th century, geometry was exclusively devoted to Euclidean geometry, which includes the notions of point, line, plane, distance, angle, surface, and curve, as fundamental concepts.[2]

During the 19th century several discoveries enlarged dramatically the scope of geometry. One of the oldest such discoveries is Gauss' Theorema Egregium (remarkable theorem) that asserts roughly that the Gaussian curvature of a surface is independent from any specific embedding in an Euclidean space. This implies that surfaces can be studied intrinsically, that is as stand alone spaces, and has been expanded into the theory of manifolds and Riemannian geometry.

Later in the 19th century, it appeared that geometries without the parallel postulate (non-Euclidean geometries) can be developed without introducing any contradiction. The geometry that underlies general relativity is a famous application of non-Euclidean geometry.

Since then, the scope of geometry has been greatly expanded, and the field has been split in many subfields that depend on the underlying methods—differential geometry, algebraic geometry, computational geometry, algebraic topology, discrete geometry (also known as combinatorial geometry) etc.—or on the properties of Euclidean spaces that are disregarded—projective geometry that consider only alignment of points but not distance and parallelism, affine geometry that omits the concept of angle and distance, finite geometry that that omits continuity, etc.

Often developed with the aim to model the physical world, geometry has applications to almost all sciences, and also to art, architecture, and other activities that are related to graphics.[3] Geometry has also applications to areas of mathematics that are apparently unrelated. For example, methods of algebraic geometry are fundamental for Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, a problem that was stated in terms of elementary arithmetic, and remainded unsolved for several centuries.

History

The earliest recorded beginnings of geometry can be traced to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt in the 2nd millennium BC.[4][5] Early geometry was a collection of empirically discovered principles concerning lengths, angles, areas, and volumes, which were developed to meet some practical need in surveying, construction, astronomy, and various crafts. The earliest known texts on geometry are the EgyptianRhind Papyrus (2000–1800 BC) and Moscow Papyrus (c. 1890 BC), the Babylonian clay tablets such as Plimpton 322 (1900 BC). For example, the Moscow Papyrus gives a formula for calculating the volume of a truncated pyramid, or frustum.[6] Later clay tablets (350–50 BC) demonstrate that Babylonian astronomers implemented trapezoid procedures for computing Jupiter's position and motion within time-velocity space. These geometric procedures anticipated the Oxford Calculators, including the mean speed theorem, by 14 centuries.[7] South of Egypt the ancient Nubians established a system of geometry including early versions of sun clocks.[8][9]

In the 7th century BC, the Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of pyramids and the distance of ships from the shore. He is credited with the first use of deductive reasoning applied to geometry, by deriving four corollaries to Thales' theorem.[10] Pythagoras established the Pythagorean School, which is credited with the first proof of the Pythagorean theorem,[11] though the statement of the theorem has a long history.[12][13]Eudoxus (408–c. 355 BC) developed the method of exhaustion, which allowed the calculation of areas and volumes of curvilinear figures,[14] as well as a theory of ratios that avoided the problem of incommensurable magnitudes, which enabled subsequent geometers to make significant advances. Around 300 BC, geometry was revolutionized by Euclid, whose Elements, widely considered the most successful and influential textbook of all time,[15] introduced mathematical rigor through the axiomatic method and is the earliest example of the format still used in mathematics today, that of definition, axiom, theorem, and proof. Although most of the contents of the Elements were already known, Euclid arranged them into a single, coherent logical framework.[16] The Elements was known to all educated people in the West until the middle of the 20th century and its contents are still taught in geometry classes today.[17]Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) of Syracuse used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, and gave remarkably accurate approximations of Pi.[18] He also studied the spiral bearing his name and obtained formulas for the volumes of surfaces of revolution.

Indian mathematicians also made many important contributions in geometry. The Satapatha Brahmana (3rd century BC) contains rules for ritual geometric constructions that are similar to the Sulba Sutras.[19] According to (Hayashi 2005, p. 363), the Śulba Sūtras contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians. They contain lists of Pythagorean triples,[20] which are particular cases of Diophantine equations.[21] In the Bakhshali manuscript, there is a handful of geometric problems (including problems about volumes of irregular solids). The Bakhshali manuscript also "employs a decimal place value system with a dot for zero."[22]Aryabhata's Aryabhatiya (499) includes the computation of areas and volumes. Brahmagupta wrote his astronomical work Brāhma Sphuṭa Siddhānta in 628. Chapter 12, containing 66 Sanskrit verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain).[23] In the latter section, he stated his famous theorem on the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral. Chapter 12 also included a formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a generalization of Heron's formula), as well as a complete description of rational triangles (i.e. triangles with rational sides and rational areas).[23]

In the Middle Ages, mathematics in medieval Islam contributed to the development of geometry, especially algebraic geometry.[24][25]Al-Mahani (b. 853) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra.[26]Thābit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin) (836–901) dealt with arithmetic operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities, and contributed to the development of analytic geometry.[27]Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) found geometric solutions to cubic equations.[28] The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Omar Khayyam and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi on quadrilaterals, including the Lambert quadrilateral and Saccheri quadrilateral, were early results in hyperbolic geometry, and along with their alternative postulates, such as Playfair's axiom, these works had a considerable influence on the development of non-Euclidean geometry among later European geometers, including Witelo (c. 1230–c. 1314), Gersonides (1288–1344), Alfonso, John Wallis, and Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri.[dubious – discuss][29]

In the early 17th century, there were two important developments in geometry. The first was the creation of analytic geometry, or geometry with coordinates and equations, by René Descartes (1596–1650) and Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665).[30] This was a necessary precursor to the development of calculus and a precise quantitative science of physics.[31] The second geometric development of this period was the systematic study of projective geometry by Girard Desargues (1591–1661).[32] Projective geometry studies properties of shapes which are unchanged under projections and sections, especially as they relate to artistic perspective.[33]

Two developments in geometry in the 19th century changed the way it had been studied previously.[34] These were the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, János Bolyai and Carl Friedrich Gauss and of the formulation of symmetry as the central consideration in the Erlangen Programme of Felix Klein (which generalized the Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries). Two of the master geometers of the time were Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866), working primarily with tools from mathematical analysis, and introducing the Riemann surface, and Henri Poincaré, the founder of algebraic topology and the geometric theory of dynamical systems. As a consequence of these major changes in the conception of geometry, the concept of "space" became something rich and varied, and the natural background for theories as different as complex analysis and classical mechanics.[35]

Important concepts in geometry

The following are some of the most important concepts in geometry.[2][36][37]

Axioms

Euclid took an abstract approach to geometry in his Elements,[38] one of the most influential books ever written.[39] Euclid introduced certain axioms, or postulates, expressing primary or self-evident properties of points, lines, and planes.[40] He proceeded to rigorously deduce other properties by mathematical reasoning. The characteristic feature of Euclid's approach to geometry was its rigor, and it has come to be known as axiomatic or synthetic geometry.[41] At the start of the 19th century, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky (1792–1856), János Bolyai (1802–1860), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) and others[42] led to a revival of interest in this discipline, and in the 20th century, David Hilbert (1862–1943) employed axiomatic reasoning in an attempt to provide a modern foundation of geometry.[43]

Points

Points are considered fundamental objects in Euclidean geometry. They have been defined in a variety of ways, including Euclid's definition as 'that which has no part'[44] and through the use of algebra or nested sets.[45] In many areas of geometry, such as analytic geometry, differential geometry, and topology, all objects are considered to be built up from points. However, there has been some study of geometry without reference to points.[46]

Lines

Euclid described a line as "breadthless length" which "lies equally with respect to the points on itself".[44] In modern mathematics, given the multitude of geometries, the concept of a line is closely tied to the way the geometry is described. For instance, in analytic geometry, a line in the plane is often defined as the set of points whose coordinates satisfy a given linear equation,[47] but in a more abstract setting, such as incidence geometry, a line may be an independent object, distinct from the set of points which lie on it.[48] In differential geometry, a geodesic is a generalization of the notion of a line to curved spaces.[49]

Planes

A plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely far.[44] Planes are used in every area of geometry. For instance, planes can be studied as a topological surface without reference to distances or angles;[50] it can be studied as an affine space, where collinearity and ratios can be studied but not distances;[51] it can be studied as the complex plane using techniques of complex analysis;[52] and so on.

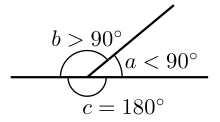

Angles

Euclid defines a plane angle as the inclination to each other, in a plane, of two lines which meet each other, and do not lie straight with respect to each other.[44] In modern terms, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle.[53]

In Euclidean geometry, angles are used to study polygons and triangles, as well as forming an object of study in their own right.[44] The study of the angles of a triangle or of angles in a unit circle forms the basis of trigonometry.[54]

In differential geometry and calculus, the angles between plane curves or space curves or surfaces can be calculated using the derivative.[55][56]

Curves

A curve is a 1-dimensional object that may be straight (like a line) or not; curves in 2-dimensional space are called plane curves and those in 3-dimensional space are called space curves.[57]

In topology, a curve is defined by a function from an interval of the real numbers to another space.[50] In differential geometry, the same definition is used, but the defining function is required to be differentiable [58] Algebraic geometry studies algebraic curves, which are defined as algebraic varieties of dimension one.[59]

Surfaces

A surface is a two-dimensional object, such as a sphere or paraboloid.[60] In differential geometry[58] and topology,[50] surfaces are described by two-dimensional 'patches' (or neighborhoods) that are assembled by diffeomorphisms or homeomorphisms, respectively. In algebraic geometry, surfaces are described by polynomial equations.[59]

Manifolds

A manifold is a generalization of the concepts of curve and surface. In topology, a manifold is a topological space where every point has a neighborhood that is homeomorphic to Euclidean space.[50] In differential geometry, a differentiable manifold is a space where each neighborhood is diffeomorphic to Euclidean space.[58]

Manifolds are used extensively in physics, including in general relativity and string theory.[61]

Length, area, and volume

Length, area, and volume describe the size or extent of an object in one dimension, two dimension, and three dimensions respectively.[62]

In Euclidean geometry and analytic geometry, the length of a line segment can often be calculated by the Pythagorean theorem.[63]

Area and volume can be defined as fundamental quantities separate from length, or they can be described and calculated in terms of lengths in a plane or 3-dimensional space.[62] Mathematicians have found many explicit formulas for area and formulas for volume of various geometric objects. In calculus, area and volume can be defined in terms of integrals, such as the Riemann integral[64] or the Lebesgue integral.[65]

Metrics and measures

The concept of length or distance can be generalized, leading to the idea of metrics.[66] For instance, the Euclidean metric measures the distance between points in the Euclidean plane, while the hyperbolic metric measures the distance in the hyperbolic plane. Other important examples of metrics include the Lorentz metric of special relativity and the semi-Riemannian metrics of general relativity.[67]

In a different direction, the concepts of length, area and volume are extended by measure theory, which studies methods of assigning a size or measure to sets, where the measures follow rules similar to those of classical area and volume.[68]

Congruence and similarity

Congruence and similarity are concepts that describe when two shapes have similar characteristics.[69] In Euclidean geometry, similarity is used to describe objects that have the same shape, while congruence is used to describe objects that are the same in both size and shape.[70]Hilbert, in his work on creating a more rigorous foundation for geometry, treated congruence as an undefined term whose properties are defined by axioms.

Congruence and similarity are generalized in transformation geometry, which studies the properties of geometric objects that are preserved by different kinds of transformations.[71]

Compass and straightedge constructions

Classical geometers paid special attention to constructing geometric objects that had been described in some other way. Classically, the only instruments allowed in geometric constructions are the compass and straightedge. Also, every construction had to be complete in a finite number of steps. However, some problems turned out to be difficult or impossible to solve by these means alone, and ingenious constructions using parabolas and other curves, as well as mechanical devices, were found.

Dimension

Where the traditional geometry allowed dimensions 1 (a line), 2 (a plane) and 3 (our ambient world conceived of as three-dimensional space), mathematicians and physicists have used higher dimensions for nearly two centuries.[72] One example of a mathematical use for higher dimensions is the configuration space of a physical system, which has a dimension equal to the system's degrees of freedom. For instance, the configuration of a screw can be described by five coordinates.[73]

In general topology, the concept of dimension has been extended from natural numbers, to infinite dimension (Hilbert spaces, for example) and positive real numbers (in fractal geometry).[74] In algebraic geometry, the dimension of an algebraic variety has received a number of apparently different definitions, which are all equivalent in the most common cases.[75]

Symmetry

The theme of symmetry in geometry is nearly as old as the science of geometry itself.[76] Symmetric shapes such as the circle, regular polygons and platonic solids held deep significance for many ancient philosophers[77] and were investigated in detail before the time of Euclid.[40] Symmetric patterns occur in nature and were artistically rendered in a multitude of forms, including the graphics of da Vinci, M.C. Escher, and others.[78] In the second half of the 19th century, the relationship between symmetry and geometry came under intense scrutiny. Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed that, in a very precise sense, symmetry, expressed via the notion of a transformation group, determines what geometry is.[79] Symmetry in classical Euclidean geometry is represented by congruences and rigid motions, whereas in projective geometry an analogous role is played by collineations, geometric transformations that take straight lines into straight lines.[80] However it was in the new geometries of Bolyai and Lobachevsky, Riemann, Clifford and Klein, and Sophus Lie that Klein's idea to 'define a geometry via its symmetry group' found its inspiration.[81] Both discrete and continuous symmetries play prominent roles in geometry, the former in topology and geometric group theory,[82][83] the latter in Lie theory and Riemannian geometry.[84][85]

A different type of symmetry is the principle of duality in projective geometry, among other fields. This meta-phenomenon can roughly be described as follows: in any theorem, exchange point with plane, join with meet, lies in with contains, and the result is an equally true theorem.[86] A similar and closely related form of duality exists between a vector space and its dual space.[87]

Contemporary geometry

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is geometry in its classical sense.[88] As it models the space of the physical world, it is used in many scientific areas, such as mechanics, astronomy, crystallography,[89] and many technical fields, such as engineering,[90]architecture,[91]geodesy,[92]aerodynamics,[93] and navigation.[94] The mandatory educational curriculum of the majority of nations includes the study of Euclidean concepts such as points, lines, planes, angles, triangles, congruence, similarity, solid figures, circles, and analytic geometry.[36]

Differential geometry

Differential geometry uses techniques of calculus and linear algebra to study problems in geometry.[95] It has applications in physics,[96]econometrics,[97] and bioinformatics,[98] among others.

In particular, differential geometry is of importance to mathematical physics due to Albert Einstein's general relativity postulation that the universe is curved.[99] Differential geometry can either be intrinsic (meaning that the spaces it considers are smooth manifolds whose geometric structure is governed by a Riemannian metric, which determines how distances are measured near each point) or extrinsic (where the object under study is a part of some ambient flat Euclidean space).[100]

Non-Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry was not the only historical form of geometry studied. Spherical geometry has long been used by astronomers, astrologers, and navigators.[101]

Immanuel Kant argued that there is only one, absolute, geometry, which is known to be true a priori by an inner faculty of mind: Euclidean geometry was synthetic a priori.[102] This view was at first somewhat challenged by thinkers such as Saccheri, then finally overturned by the revolutionary discovery of non-Euclidean geometry in the works of Bolyai, Lobachevsky, and Gauss (who never published his theory).[103] They demonstrated that ordinary Euclidean space is only one possibility for development of geometry. A broad vision of the subject of geometry was then expressed by Riemann in his 1867 inauguration lecture Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen (On the hypotheses on which geometry is based),[104] published only after his death. Riemann's new idea of space proved crucial in Albert Einstein's general relativity theory. Riemannian geometry, which considers very general spaces in which the notion of length is defined, is a mainstay of modern geometry.[81]

Topology

Topology is the field concerned with the properties of continuous mappings,[105] and can be considered a generalization of Euclidean geometry.[106] In practice, topology often means dealing with large-scale properties of spaces, such as connectedness and compactness.[50]

The field of topology, which saw massive development in the 20th century, is in a technical sense a type of transformation geometry, in which transformations are homeomorphisms.[107] This has often been expressed in the form of the saying 'topology is rubber-sheet geometry'. Subfields of topology include geometric topology, differential topology, algebraic topology and general topology.[108]

Algebraic geometry

What’s New in the 3D Geometrical Objects v1.3 by REVENGE serial key or number?

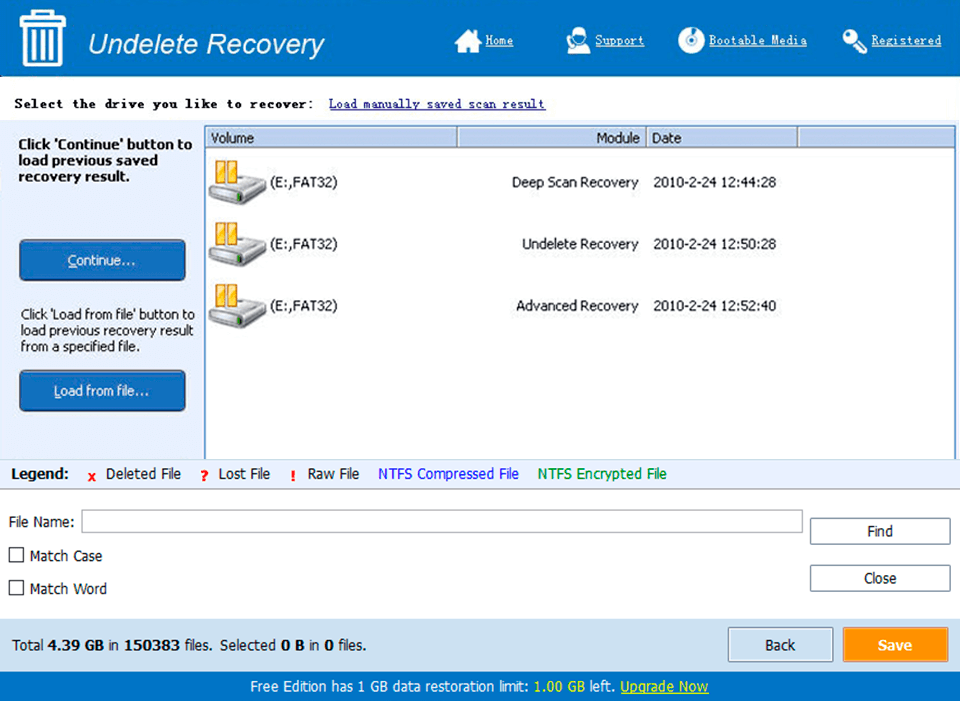

Screen Shot

System Requirements for 3D Geometrical Objects v1.3 by REVENGE serial key or number

- First, download the 3D Geometrical Objects v1.3 by REVENGE serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: