Small Business Inventory Control v3.5 serial key or number

Small Business Inventory Control v3.5 serial key or number

ペルケ インド牛革くるみホックラウンド長財布 本革 レザー 08-06-03301 PI One Size

約4,197,000件

検索ツール

91 out of 100 based on 1977 user ratings

出雲・米子・松江で素敵な住まいづくりを実現

ペルケ インド牛革くるみホックラウンド長財布 本革 レザー 08-06-03301 PI One Size

商品説明

商品サイズ

高さ : 3.81 cm

横幅 : 13.72 cm

奥行 : 22.60 cm

重量 : 340.0 g

- ペルケ インド牛革くるみホックラウンド長財布 本革 レザー 08-06-03301 PI One Size NEWS 一覧へ

あなたはどんな家を建てたいですか?

でも、完全なオーダーは費用や時間がかかります。それをバランスよくまとめようとするのが「ひのきのいえ」の考え方です。

その気密・断熱の高い性能から、少しのエネルギーで快適に暮らせる、省エネ住宅です。

住まい手の感性や嗜好に合わせて、豊かな暮らしを楽しむためのシンプルな木の家です。

施工事例検索

お客様の声 voice- 本社

- 0853-72-9394 [営業時間]8:30-17:30[定休日]不定休

- 会社案内

- 暮らしのステーション 〜ソラマドの家モデルハウス〜

- 0853-25-8500 [営業時間]10:00-18:00[定休日]火・水

- 詳細を見る

- ペルケ インド牛革くるみホックラウンド長財布 本革 レザー 08-06-03301 PI One Size

- 米子オフィス

- 0859-30-4777 [営業時間]8:30-17:30[定休日]不定休

- 詳細を見る

History of IBM

International Business Machines (IBM), nicknamed "Big Blue", is a multinational computer technology and IT consulting corporation headquartered in Armonk, New York, United States. IBM originated from the bringing together of several companies that worked to automate routine business transactions, including the first companies to build punched card based data tabulating machines and to build time clocks. In 1911, these companies were amalgamated into the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR).

Thomas J. Watson (1874-1956) joined the company in 1914 as General Manager and became its President in 1915. In 1924 the company changed its name to "International Business Machines." IBM expanded into electric typewriters and other office machines. Watson was a salesman and concentrated on building a highly motivated, very well paid sales force that could craft solutions for clients unfamiliar with the latest technology. His motto was "THINK". Customers were advised to not "fold, spindle, or mutilate" the cardboard cards. IBM's first experiments with computers in the 1940s and 1950s were modest advances on the card-based system. Its great breakthrough came in the 1960s with its System/360 family of mainframe computers. IBM offered a full range of hardware, software, and service agreements, so that users, as their needs grew, would stay with "Big Blue." Since most software was custom-written by in-house programmers and would run on only one brand of computers, it was too expensive to switch brands. Brushing off clone makers, and facing down a federal anti-trust suit, the giant sold reputation and security as well as hardware and was the most admired American corporation of the 1970s and 1980s.

The late 1980s and early 1990s were difficult for IBM—losses in 1993 exceeded $8 billion—as the mainframe giant failed to adjust quickly enough to the personal computer revolution.[1] Desktop machines had the power needed and were vastly easier for both users and managers than multi-million-dollar mainframes. IBM did introduce a popular line of microcomputers—but it was too popular. Clone makers undersold IBM, while the profits went to chip makers like Intel or software houses like Microsoft.

After a series of reorganizations, IBM remains one of the world's largest computer companies and systems integrators.[2] With over 400,000 employees worldwide as of 2014,[3] IBM holds more patents than any other U.S. based technology company and has twelve research laboratories worldwide.[4][5] The company has scientists, engineers, consultants, and sales professionals in over 175 countries.[6] IBM employees have earned five Nobel Prizes, four Turing Awards, five National Medals of Technology, and five National Medals of Science.[7]

Chronology[edit]

1880s–1924: The origin of IBM[edit]

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1890 | ||

| 1895 | ||

| 1900 | ||

| 1905 | ||

| 1910 | ||

| 1915 | 4 | 1,672 |

| 1920 | 14 | 2,731 |

| 1925 | 13 | 3,698 |

The roots of IBM date back to the 1880s, tracing from four predecessor companies:[8][9][10][11]

On June 16, 1911, these four companies were amalgamated into a new holding company named the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (CTR), based in Endicott.[12][13][14][15] The amalgamation was engineered by noted financier Charles Flint. Flint remained a member of the board of CTR until his retirement in 1930.[16] At the time of the amalgamation, CTR had 1,300 employees and offices and plants in Endicott and Binghamton, New York; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; Washington, D.C.; and Toronto, Ontario.

After amalgamation, the individual companies continued to operate using their established names, as subsidiaries of CTR, until the holding company was eliminated in 1933.[17] The divisions manufactured a wide range of products, including employee time-keeping systems, weighing scales, automatic meat slicers, coffee grinders, and punched card equipment. The product lines were very different; Flint stated that the "allied" consolidation:

... instead of being dependent for earnings upon a single industry, would own three separate and distinct lines of business, so that in normal times the interest and sinking funds on its bonds could be earned by any one of these independent lines, while in abnormal times the consolidation would have three chances instead of one to meet its obligations and pay dividends.[18]

Of the companies amalgamated to form CTR, the most technologically significant was The Tabulating Machine Company, founded by Herman Hollerith, and specialized in the development of punched card data processing equipment. Hollerith's series of patents on tabulating machine technology, first applied for in 1884, drew on his work at the U.S. Census Bureau from 1879–82. Hollerith was initially trying to reduce the time and complexity needed to tabulate the 1890 Census. His development of punched cards in 1886 set the industry standard for the next 80 years of tabulating and computing data input.[19]

In 1896, The Tabulating Machine Company leased some machines to a railway company[20] but quickly focused on the challenges of the largest statistical endeavor of its day – the 1900 US Census. After winning the government contract, and completing the project, Hollerith was faced with the challenge of sustaining the company in non-Census years. He returned to targeting private businesses in the United States and abroad, attempting to identify industry applications for his automatic punching, tabulating and sorting machines. In 1911, Hollerith, now 51 and in failing health sold the business to Flint for $2.3 million (of which Hollerith got $1.2 million), who then founded CTR. When the diversified businesses of CTR proved difficult to manage, Flint turned for help to the former No. 2 executive at the National Cash Register Company (NCR), Thomas J. Watson, Sr.. Watson became General Manager of CTR in 1914 and President in 1915. By drawing upon his managerial experience at NCR, Watson quickly implemented a series of effective business tactics: generous sales incentives, a focus on customer service, an insistence on well-groomed, dark-suited salesmen, and an evangelical fervor for instilling company pride and loyalty in every worker. As the sales force grew into a highly professional and knowledgeable arm of the company, Watson focused their attention on providing large-scale tabulating solutions for businesses, leaving the market for small office products to others. He also stressed the importance of the customer, a lasting IBM tenet. The strategy proved successful, as, during Watson's first four years, revenues doubled to $2 million, and company operations expanded to Europe, South America, Asia, and Australia.

At the helm during this period, Watson played a central role in establishing what would become the IBM organization and culture. He launched a number of initiatives that demonstrated an unwavering faith in his workers. He hired the company's first disabled worker in 1914, he formed the company's first employee education department in 1916 and in 1915 he introduced his favorite slogan, "THINK", which quickly became the corporate mantra. Watson boosted company spirit by encouraging any employee with a complaint to approach him or any other company executive – his famed Open Door policy. He also sponsored employee sports teams, family outings, and a company band, believing that employees were most productive when they were supported by healthy and supportive families and communities. These initiatives – each deeply rooted in Watson's personal values system – became core aspects of IBM culture for the remainder of the century.

"Watson had never liked the clumsy hyphenated title of the CTR" and chose to replace it with the more expansive title "International Business Machines".[21] First as a name for a 1917 Canadian subsidiary, then as a line in advertisements. Finally, on February 14, 1924, the name was used for CTR itself.

Key events[edit]

- 1890-1895: Hollerith's punched cards used for 1890 Census. The U.S. Census Bureau contracts to use Herman Hollerith's punched card tabulating technology on the 1890 United States Census. That census was completed in 6-years and estimated to have saved the government $5 million.[22] The prior, 1880, census had required 8-years. The years required are not directly comparable; the two differed in: population size, data collected, resources (census bureau headcount, machines, ...), and reports prepared. The total population of 62,947,714, the family, or rough, count, was announced after only six weeks of processing (punched cards were not used for this tabulation).[23][24] Hollerith's punched cards become the tabulating industry standard for input for the next 70 years. Hollerith's The Tabulating Machine Company is later consolidated into what becomes IBM.

- 1906: Hollerith Type I Tabulator. The first tabulator with an automatic card feed and control panel.[25]

- 1911: Formation. Charles Flint, a noted trust organizer, engineers the amalgamation of four companies: The Tabulating Machine Company, the International Time Recording Company, the Computing Scale Company of America, and the Bundy Manufacturing Company. The amalgamated companies manufacture and sell or lease machinery such as commercial scales, industrial time recorders, meat and cheese slicers, tabulators, and punched cards. The new holding company, Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company, is based in Endicott. Including the amalgamated subsidiaries, CTR had 1,300 employees with offices and plants in Endicott and Binghamton, New York; Dayton, Ohio; Detroit, Michigan; and Washington, D.C.[26][27]

- 1914: Thomas J. Watson arrives. Thomas J. Watson Sr., a one-year jail sentence pending – see NCR – is made general manager of CTR. Less than a year later the court verdict was set aside. A consent decree was drawn up which Watson refused to sign, gambling that there would not be a retrial. He becomes president of the firm Monday, March 15, 1915.[28]

- 1914: First disabled employee. CTR companies hire their first disabled employee.[29]

- 1916: Employee education. CTR invests in its subsidiary's employees, creating an education program. Over the next two decades, the program would expand to include management education, volunteer study clubs, and the construction of the IBM Schoolhouse in 1933.[31]

- 1917: CTR in Brazil. Premiered in Brazil in 1917, invited by the Brazilian Government to conduct the census, CTR opened an office in Brazil[32]

- 1920: First Tabulating Machine Co. printing tabulator. With prior tabulators the results were displayed and had to be copied by hand.[33]

- 1923: CTR Germany. CTR acquires majority ownership of the German tabulating firm Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen Groupe (Dehomag).

- 1924: International Business Machines Corporation. "Watson had never liked the clumsy hyphenated title of Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company" and chose the new name both for its aspirations and to escape the confines of "office appliance". The new name was first used for the company's Canadian subsidiary in 1917. On February 14, 1924, CTR's name was formally changed to International Business Machines Corporation (IBM).[21] The subsidiaries' names did not change; there would be no IBM labeled products until 1933 (below) when the subsidiaries are merged into IBM.

1925–1929: IBM's early growth[edit]

Our products are known in every zone. Our reputation sparkles like a gem. We've fought our way through and new fields we're sure to conquer too. For the ever-onward IBM

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1925 | 13 | 3,698 |

Watson mandated strict rules for employees, including a dress code of dark suits, white shirts and striped ties, and no alcohol, whether working or not. He led the singing at meetings of songs such as "Ever Onward" from the official IBM songbook.[34] The company launched an employee newspaper, Business Machines, which unified coverage of all of IBM's businesses under one publication.[35] IBM introduced the Quarter Century Club,[36] to honor employees with 25 years of service to the company, and launched the Hundred Percent Club, to reward sales personnel who met their annual quotas.[37] In 1928, the Suggestion Plan program – which granted cash rewards to employees who contributed viable ideas on how to improve IBM products and procedures – made its debut.[38]

IBM and its predecessor companies made clocks and other time recording products for 70 years, culminating in the 1958 sale of the IBM Time Equipment Division to Simplex Time Recorder Company,[40] IBM manufactured and sold such equipment as dial recorders, job recorders, recording door locks, time stamps and traffic recorders.[41][42]

The company also expanded its product line through innovative engineering. Behind a core group of inventors – James W. Bryce, Clair Lake,[43] Fred Carroll,[44] and Royden Pierce[45] – IBM produced a series of significant product innovations. In the optimistic years following World War I, CTR's engineering and research staff developed new and improved mechanisms to meet the broadening needs of its customers. In 1920, the company introduced the first complete school time control system,[46] and launched its first printing tabulator.[47] Three years later the company introduced the first electric keypunch,[48] and 1924's Carroll Rotary Press produced punched cards at previously unheard of speeds.[35] In 1928, the company held its first customer engineering education class, demonstrating an early recognition of the importance of tailoring solutions to fit customer needs.[49] It also introduced the 80-column punched card in 1928, which doubled its information capacity.[49] This new format, soon dubbed the "IBM Card", became and remained an industry standard until the 1970s.

Key events[edit]

- 1925: First tabulator sold to Japan. In May 1925, Morimura-Brothers entered into a sole agency agreement with IBM to import Hollerith tabulators into Japan. The first Hollerith tabulator in Japan was installed at Nippon Pottery (now Noritake) in September 1925, making it IBM customer #1 in Japan.[50][51][52]

- 1927: IBM Italy'. IBM opens its first office in Italy in Milan, and starts selling and operating with National Insurance and Banks.

- 1928: A Tabulator that can subtract, Columbia University, 80-column card. The first Hollerith tabulator that could subtract, the Hollerith Type IV tabulator.[53] IBM begins its collaboration with Benjamin Wood, Wallace John Eckert and the Statistical Bureau at Columbia University.[54][55] The Hollerith 80-column punched card is introduced. Its rectangular holes are patented, ending vendor compatibility (of the prior 45 column card; Remington Rand would soon introduce a 90 column card).[56]

1930–1938: The Great Depression[edit]

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1930 | 19 | 6,346 |

| 1935 | 21 | 8,654 |

The Great Depression of the 1930s presented an unprecedented economic challenge, and Watson met the challenge head-on, continuing to invest in people, manufacturing, and technological innovation despite the difficult economic times. Rather than reduce staff, he hired additional employees in support of President Franklin Roosevelt's National Recovery Administration plan – not just salesmen, which he joked that he had a lifelong weakness for, but engineers too. Watson not only kept his workforce employed, but he also increased their benefits. IBM was among the first corporations to provide group life insurance (1934), survivor benefits (1935), and paid vacations (1936). He upped his ante on his workforce by opening the IBM Schoolhouse in Endicott to provide education and training for IBM employees. And he greatly increased IBM's research capabilities by building a modern research laboratory on the Endicott manufacturing site.

With all this internal investment, Watson was, in essence, gambling on the future. It was IBM's first ‘Bet the Company’ gamble, but the risk paid off handsomely. Watson's factories, running full tilt for six years with no market to sell to, created a huge inventory of unused tabulating equipment, straining IBM's resources. To reduce the cash drain, the struggling Dayton Scale Division (the food services equipment business) was sold in 1933 to Hobart Manufacturing for stock.[57][58] When the Social Security Act of 1935 – labeled as "the biggest accounting operation of all time"[59] – came up for bid, IBM was the only bidder that could quickly provide the necessary equipment. Watson's gamble brought the company a landmark government contract to maintain employment records for 26 million people. IBM's successful performance on the contract soon led to other government orders, and by the end of the decade, IBM had not only safely negotiated the Depression but risen to the forefront of the industry. Watson's Depression-era decision to invest heavily in technical development and sales capabilities, education to expand the breadth of those capabilities, and his commitment to the data processing product line laid the foundation for 50 years of IBM growth and successes.

His avowed focus on international expansion proved an equally key component of the company's 20th-century growth and success. Watson, having witnessed the havoc the First World War wrought on society and business, envisioned commerce as an obstacle to war. He saw business interests and peace as being mutually compatible. In fact, he felt so strongly about the connection between the two that he had his slogan "World Peace Through World Trade" carved into the exterior of IBM's new World Headquarters (1938) in New York City.[60] The slogan became an IBM business mantra, and Watson campaigned tirelessly for the concept with global business and government leaders. He served as an informal, unofficial government host for world leaders when they visited New York, and received numerous awards from foreign governments for his efforts to improve international relations through the formation of business ties.

Key events[edit]

- 1931: The first Hollerith punched card machine that could multiply, the first Hollerith alphabetical accounting machine. The Hollerith 600 Multiplying Punch.[61] The first Hollerith alphabetical accounting machine – although not a complete alphabet, the Alphabetic Tabulator Model B was quickly followed by the full alphabet ATC.[56]

- 1931: Super Computing Machine. The term Super Computing Machine is used by the New York World newspaper to describe the Columbia Difference Tabulator, a one-of-a-kind special purpose tabulator-based machine made for the Columbia Statistical Bureau, a machine so massive it was nicknamed Packard.[62][63] The Packard attracted users from across the country: "the Carnegie Foundation, Yale, Pittsburgh, Chicago, Ohio State, Harvard, California and Princeton."[64]

- 1933: Subsidiary companies are merged into IBM. The Tabulating Machine Company name, and others, disappear as subsidiary companies are merged into IBM.[65][66]

- 1933: Removable control panels. IBM introduces removable control panels.[67]

- 1933: 40-hour week. IBM introduces the 40-hour week for both manufacturing and office locations.

- 1933: Electromatic Typewriter Co. purchased. Purchased primarily to get important patents safely into IBM hands, electric typewriters would become one of IBM's most widely known products.[68] By 1958 IBM was deriving 8% of its revenue from the sale of electric typewriters.[69]

- 1934 – Group life insurance. IBM creates a group life insurance plan for all employees with at least one year of service.[70]

- 1934: Elimination of piece work. Watson, Sr., places IBM's factory employees on salary, eliminating piece work and providing employees and their families with an added degree of economic stability.[71]

- 1934: IBM 801. The IBM 801 Bank Proof machine to clear bank checks is introduced. A new type of proof machine, the 801 lists and separates checks, endorses them, and records totals. It dramatically improves the efficiency of the check clearing process.[72]

- 1935: Social Security Administration. During the Great Depression, IBM keeps its factories producing new machines even while demand is slack. When Congress passes the Social Security Act in 1935, IBM – with its overstocked inventory – is consequently positioned to win the landmark government contract, which is called "the biggest accounting operation of all time."[73]

- 1936: Supreme Court rules IBM can only set punched card specifications. IBM initially required that its customers use only IBM manufactured cards with IBM machines, which were leased, not sold. IBM viewed its business as providing a service and that the cards were part of the machine. In 1932 the government took IBM to court on this issue. IBM fought all the way to the Supreme Court and lost in 1936; the court ruling that IBM could only set card specifications.[74]

- 1937: Scientific computing. The tabulating machine data center established at Columbia University, dedicated to scientific research, is named the Thomas J. Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau.[75]

- 1937: IBM produces 5 to 10 million punched cards every day. By 1937... IBM had 32 presses at work in Endicott, N.Y., printing, cutting and stacking five to 10 million punched cards every day.[77]

- 1937: Paid holidays, paid vacation. IBM announces a policy of paying employees for six annual holidays and becomes one of the first U.S. companies to grant holiday pay. Paid vacations also begin."[81]

- 1937: IBM Japan. Japan Wattoson Statistics Accounting Machinery Co., Ltd. (日本ワットソン統計会計機械株式会社, now IBM Japan) was established.[51]

- 1938: New headquarters. When IBM dedicates its new World Headquarters on 590 Madison Avenue, New York, New York, in January 1938, the company has operations in 79 countries.[60]

1939–1945: World War II[edit]

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1940 | 45 | 12,656 |

| 1945 | 138 | 18,257 |

In the decades leading up to the onset of WW2 IBM had operations in many countries that would be involved in the war, on both the side of the Allies and the Axis. IBM had a lucrative subsidiary in Germany, which it was the majority owner of, as well as operations in Poland, Switzerland, and other countries in Europe. As with most other enemy-owned businesses in Axis countries, these subsidiaries were taken over by the Nazis and other Axis governments early on in the war. The headquarters in New York meanwhile worked to help the American war effort.

IBM in America[edit]

IBM's product line[82] shifted from tabulating equipment and time recording devices to Sperry and Norden bombsights, Browning Automatic Rifle and the M1 Carbine, and engine parts – in all, more than three dozen major ordnance items and 70 products overall. Watson set a nominal one percent profit on those products and used the profits to establish a fund for widows and orphans of IBM war casualties.[83]

Allied military forces widely utilized IBM's tabulating equipment for mobile records units, ballistics, accounting and logistics, and other war-related purposes. There was extensive use of IBM punched-card machines for calculations made at Los Alamos during the Manhattan Project for developing the first atomic bombs.[84] During the War, IBM also built the Automatic Sequence Controlled Calculator, also known as the Harvard Mark I for the U.S. Navy – the first large-scale electromechanical calculator in the U.S..

In 1933 IBM had acquired the rights to Radiotype, an IBM Electric typewriter attached to a radio transmitter.[85] "In 1935 Admiral Richard E. Byrd successfully sent a test Radiotype message 11,000 miles from Antarctica to an IBM receiving station in Ridgewood, New Jersey"[86] Selected by the Signal Corps for use during the war, Radiotype installations handled up to 50,000,000 words a day.[87]

To meet wartime product demands, IBM greatly expanded its manufacturing capacity. IBM added new buildings at its Endicott, New York plant (1941), and opened new facilities in Poughkeepsie, New York (1941), Washington, D.C. (1942),[88] and San Jose, California (1943).[89] IBM's decision to establish a presence on the West Coast took advantage of the growing base of electronics research and other high technology innovation in the southern part of the San Francisco Bay Area, an area that came to be known many decades later as Silicon Valley.

IBM was, at the request of the government, the subcontractor for the Japanese internment camps' punched card project.[90]

IBM equipment was used for cryptography by US Army and Navy organizations, Arlington Hall and OP-20-G and similar Allied organizations using Hollerith punched cards (Central Bureau and the Far East Combined Bureau).

IBM in Germany and Nazi Occupied Europe[edit]

The Nazis made extensive use of Hollerith equipment and IBM's majority-owned German subsidiary, Deutsche Hollerith Maschinen GmbH (Dehomag), supplied this equipment from the early 1930s. This equipment was critical to Nazi efforts to categorize citizens of both Germany and other nations that fell under Nazi control through ongoing censuses. This census data was used to facilitate the round-up of Jews and other targeted groups, and to catalog their movements through the machinery of the Holocaust, including internment in the concentration camps.

As with hundreds of foreign-owned companies that did business in Germany at that time, Dehomag came under the control of Nazi authorities prior to and during World War II. A Nazi, Hermann Fellinger, was appointed by the Germans as an enemy-property custodian and placed at the head of the Dehomag subsidiary.

Historian and author Edwin Black, in his best selling book on the topic, maintains that the seizure of the German subsidiary was a ruse. He writes: "The company was not looted, its leased machines were not seized, and [IBM] continued to receive money funneled through its subsidiary in Geneva."[91] In his book he argues that IBM was an active and enthusiastic supplier to the Nazi regime long after they should have stopped dealing with them. Even after the invasion of Poland, IBM continued to service and expand services to the Third Reich in Poland and Germany.[91] The seizure of IBM came after Pearl Harbor and the US Declaration of War, in 1941.

IBM responded that the book was based upon "well-known" facts and documents that it had previously made publicly available and that there were no new facts or findings.[92] IBM also denied withholding any relevant documents.[93] Writing in the New York Times, Richard Bernstein argued that Black overstates IBM's culpability.[94]

Key events[edit]

- 1942: Training for the disabled. IBM launches a program to train and employ disabled people in Topeka, Kansas. The next year classes begin in New York City, and soon the company is asked to join the President's Committee for Employment of the Handicapped.[95]

- 1943: First female vice president. IBM appoints its first female vice president.[96]

- 1944: ASCC. IBM introduces the world's first large-scale calculating computer, the Automatic Sequence Control Calculator (ASCC). Designed in collaboration with Harvard University, the ASCC, also known as the Mark I, uses electromechanical relays to solve addition problems in less than a second, multiplication in six seconds, and division in 12 seconds.[97]

- 1944: United Negro College Fund. IBM President Thomas J. Watson, Sr., joins the Advisory Committee of the United Negro College Fund (UNCF), and IBM contributes to the UNCF's fund-raising efforts.[98]

- 1945: IBM's first research lab. IBM's first research facility, the Watson Scientific Computing Laboratory, opens in a renovated fraternity house near Columbia University in Manhattan. In 1961, IBM moves its research headquarters to the T.J. Watson Research Center in Yorktown Heights, New York.[99]

1946–1959: Postwar recovery, rise of business computing, space exploration, the Cold War[edit]

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1950 | 266 | 30,261 |

| 1955 | 696 | 56,297 |

| 1960 | 1,810 | 104,241 |

IBM had expanded so much by the end of the War that the company faced a potentially difficult situation – what would happen if military spending dropped sharply? One way IBM addressed that concern was to accelerate its international growth in the years after the war, culminating with the formation of the World Trade Corporation in 1949 to manage and grow its foreign operations. Under the leadership of Watson's youngest son, Arthur K. ‘Dick’ Watson, the WTC would eventually produce half of IBM's bottom line by the 1970s.

Despite introducing its first computer a year after Remington Rand's UNIVAC in 1951, within five years IBM had 85% of the market. A UNIVAC executive complained that "It doesn't do much good to build a better mousetrap if the other guy selling mousetraps has five times as many salesmen".[34] With the death of Founding Father Thomas J. Watson, Sr. on June 19, 1956 at age 82, IBM experienced its first leadership change in more than four decades. The mantle of chief executive fell to his eldest son, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., IBM's president since 1952.

The new chief executive faced a daunting task. The company was in the midst of a period of rapid technological change, with nascent computer technologies – electronic computers, magnetic tape storage, disk drives, programming – creating new competitors and market uncertainties. Internally, the company was growing by leaps and bounds, creating organizational pressures and significant management challenges. Lacking the force of personality that Watson Sr. had long used to bind IBM together, Watson Jr. and his senior executives privately wondered if the new generation of leadership was up to challenge of managing a company through this tumultuous period.[100] "We are," wrote one longtime IBM executive in 1956, "in grave danger of losing our "eternal" values that are as valid in electronic days as in mechanical counter days."

Watson Jr. responded by drastically restructuring the organization mere months after his father died, creating a modern management structure that enabled him to more effectively oversee the fast-moving company.[101] He codified well known but unwritten IBM practices and philosophy into formal corporate policies and programs – such as IBM's Three Basic Beliefs, and Open Door and Speak Up! Perhaps the most significant of which was his shepherding of the company's first equal opportunity policy letter into existence in 1953, one year before the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Brown vs. Board of Education and 11 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[102] He continued to expand the company's physical capabilities – in 1952 IBM San Jose launched a storage development laboratory that pioneered disk drives. Major facilities would later follow in Rochester, Minnesota; Greencastle, Indiana; Kingston, New York; and Lexington, Kentucky. Concerned that IBM was too slow in adapting transistor technology Watson requested a corporate policy regarding their use, resulting in this unambiguous 1957 product development policy statement: "It shall be the policy of IBM to use solid-state circuitry in all machine developments. Furthermore, no new commercial machines or devices shall be announced which make primary use of tube circuitry."[103]

Watson Jr. also continued to partner with the United States government to drive computational innovation. The emergence of the Cold War accelerated the government's growing awareness of the significance of digital computing and drove major Department of Defense supported computer development projects in the 1950s. Of these, none was more important than the SAGEinterceptor early detection air defense system.

In 1952, IBM began working with MIT's Lincoln Laboratory to finalize the design of an air defense computer. The merger of academic and business engineering cultures proved troublesome, but the two organizations finally hammered out a design by the summer of 1953, and IBM was awarded the contract to build two prototypes in September.[104] In 1954, IBM was named as the primary computer hardware contractor for developing SAGE for the United States Air Force. Working on this massive computing and communications system, IBM gained access to pioneering research being done at Massachusetts Institute of Technology on the first real-time, digital computer. This included working on many other computer technology advancements such as magnetic core memory, a large real-time operating system, an integrated video display, light guns, the first effective algebraic computer language, analog-to-digital and digital-to-analog conversion techniques, digital data transmission over telephone lines, duplexing, multiprocessing, and geographically distributed networks. IBM built fifty-six SAGE computers at the price of US$30 million each, and at the peak of the project devoted more than 7,000 employees (20% of its then workforce) to the project. SAGE had the largest computer footprint ever and continued in service until 1984.[105]

More valuable to IBM in the long run than the profits from governmental projects, however, was the access to cutting-edge research into digital computers being done under military auspices. IBM neglected, however, to gain an even more dominant role in the nascent industry by allowing the RAND Corporation to take over the job of programming the new computers, because, according to one project participant, Robert P. Crago, "we couldn't imagine where we could absorb two thousand programmers at IBM when this job would be over someday, which shows how well we were understanding the future at that time."[106] IBM would use its experience designing massive, integrated real-time networks with SAGE to design its SABRE airline reservation system, which met with much success.

These government partnerships, combined with pioneering computer technology research and a series of commercially successful products (IBM's 700 series of computer systems, the IBM 650, the IBM 305 RAMAC (with disk drive memory), and the IBM 1401) enabled IBM to emerge from the 1950s as the world's leading technology firm. Watson Jr. had answered his self-doubt. In the five years since the passing of Watson Sr., IBM was two and a half times bigger, its stock had quintupled, and of the 6000 computers in operation in the United States, more than 4000 were IBM machines.[107]

Key events[edit]

- 1946: IBM 603. IBM announces the IBM 603 Electronic Multiplier, the first commercial product to incorporate electronic arithmetic circuits. The 603 used vacuum tubes to perform multiplication far more rapidly than earlier electromechanical devices. It had begun its development as part of a program to make a "super calculator" that would perform faster than 1944's IBM ASCC by using electronics.[108]

- 1946: Chinese character typewriter. IBM introduces an electric Chinese ideographic character typewriter, which allowed an experienced user to type at a rate of 40 to 45 Chinese words a minute. The machine utilizes a cylinder on which 5,400 ideographic type faces are engraved.[109]

- 1948: IBM SSEC. IBM's first large-scale digital calculating machine, the Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator, is announced. The SSEC is the first computer that can modify a stored program and featured 12,000 vacuum tubes and 21,000 electromechanical relays.[111]

- 1950s: Space exploration. From developing ballistics tables during World War II to the design and development of intercontinental missiles to the launching and tracking of satellites to manned lunar and shuttle space flights, IBM has been a contractor to NASA and the aerospace industry.[112]

- 1952: IBM 701. IBM throws its hat into the computer business ring by introducing the 701, its first large-scale electronic computer to be manufactured in quantity. The 701, IBM President Thomas J. Watson, Jr., later recalled, is "the machine that carried us into the electronics business."[113]

- 1952: Magnetic tape vacuum column. IBM introduces the magnetic tape drive vacuum column, making it possible for fragile magnetic tape to become a viable data storage medium. The use of the vacuum column in the IBM 701 system signals the beginning of the era of magnetic storage, as the technology becomes widely adopted throughout the industry.[114]

- 1952: First California research lab. IBM opens its first West Coast lab in San Jose, California: the area that decades later will come to be known as "Silicon Valley." Within four years, the lab begins to make its mark by inventing the hard disk drive.[113]

- 1953: IBM 650. IBM announces the IBM 650 Magnetic Drum Data-Processing Machine, an intermediate size electronic computer, to handle both business and scientific computations. A hit with both universities and businesses, it was the most popular computer of the 1950s. Nearly 2,000 IBM 650s were marketed by 1962.[115]

- 1954: NORC. IBM develops and builds the fastest, most powerful electronic computer of its time: the Naval Ordnance Research Computer (NORC): for the U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance.[116]

- 1956: First magnetic Hard disk drive. IBM introduces the world's first magnetic hard disk for data storage. The IBM 305 RAMAC (Random Access Method of Accounting and Control) offers an unprecedented performance by permitting random access to any of the million characters distributed over both sides of 50 two-foot-diameter disks. Produced in California, IBM's first hard disk stored about 2,000 bits of data per square inch and cost about $10,000 per megabyte. By 1997, the cost of storing a megabyte had dropped to around ten cents.[117]

- 1956: Consent decree. The United States Justice Department enters a consent decree against IBM in 1956 to prevent the company from becoming a monopoly in the market for punched-card tabulating and, later, electronic data-processing machines. The decree requires IBM to sell its computers as well as lease them and to service and sell parts for computers that IBM no longer owned.[118]

- 1956: Corporate design. In the mid-1950s, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., was struck by how poorly IBM was handling corporate design. He hired design consultant Eliot Noyes to oversee the creation of a formal Corporate Design Program and charged Noyes with creating a consistent, world-class look and feel at IBM. Over the next two decades, Noyes hired a host of influential architects, designers, and artists to design IBM products, structures, exhibits, and graphics. The list of Noyes contacts includes such iconic figures as Eero Saarinen, Marcel Breuer, Mies van der Rohe, John Bolles, Paul Rand, Isamu Noguchi and Alexander Calder.[119]

- 1956: First European research lab. IBM opens its first research lab outside the United States, in the Swiss city of Zurich.[120]

- 1956: Changing hands. Watson Sr. retires and hands IBM to his son, Watson Jr. Senior dies soon after.[121]

- 1956: Williamsburg conference. Watson Jr. gathered some 100 senior IBM executives together for a special three-day meeting in Williamsburg, Virginia. The meeting resulted in a new organizational structure that featured a six-member corporate management committee and delegated more authority to business unit leadership. It was the first major meeting IBM had ever held without Thomas J. Watson Sr., and it marked the emergence of the second generation of IBM leadership.[122]

- 1956: Artificial intelligence. Arthur L. Samuel of IBM's Poughkeepsie, New York, laboratory programs an IBM 704 to play checkers (English draughts) using a method in which the machine can "learn" from its own experience. It is believed to be the first "self-learning" program, a demonstration of the concept of artificial intelligence.[123]

- 1957: FORTRAN. IBM revolutionizes programming with the introduction of FORTRAN (Formula Translator), which soon becomes the most widely used computer programming language for technical work. FORTRAN is still the basis for many important numerical analysis programs.[124]

- 1958: IBM domestic Time Equipment Division sold to Simplex. IBM announces the sale of the domestic Time Equipment Division (clocks et al.) business to Simplex Time Recorder Company. The IBM time equipment service force will be transferred to the Electric Typewriter Division.[126]

- 1958: Open Door program. First implemented by Watson, Sr., in the 1910s, the Open Door was a traditional company practice that granted employees with complaints hearings with senior executives, up to and including Watson Sr. IBM formalized this practice into policy in 1958 with the creation of the Open Door Program.[127]

- 1959: Speak up! A further example of IBM's willingness to solicit and act upon employee feedback, the Speak Up! Program was first created in San Jose.[128]

- 1959: IBM 1401. IBM introduces 1401, the first high-volume, stored-program, core-memory, transistorized computer. Its versatility in running enterprise applications of all kinds helped it become the most popular computer model in the world in the early 1960s.[129]

- 1959: IBM 1403. IBM introduces the 1403 chain printer, which launches the era of high-speed, high-volume impact printing. The 1403 will not be surpassed for print quality until the advent of laser printing in the 1970s.[130]

1960–1969: The System/360 era, Unbundling software and services[edit]

| Year | Gross income (in $m) | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1955 | 696 | 56,297 |

| 1960 | 1,810 | 104,241 |

| 1965 | 3,750 | 172,445 |

| 1970 | 7,500 | 269,291 |

On April 7, 1964, IBM introduced the revolutionary System/360, the first large "family" of computers to use interchangeable software and peripheral equipment, a departure from IBM's existing product line of incompatible machines, each of which was designed to solve specific customer requirements.[131] The idea of a general-purpose machine was considered a gamble at the time.[132]

Within two years, the System/360 became the dominant mainframe computer in the marketplace and its architecture became a de facto industry standard. During this time, IBM transformed from a medium-sized maker of tabulating equipment and typewriters into the world's largest computer company.[133]

In 1969 IBM "unbundled" software and services from hardware sales. Until this time customers did not pay for software or services separately from the very high price for the hardware. Software was provided at no additional charge, generally in source code form. Services (systems engineering, education and training, system installation) were provided free of charge at the discretion of the IBM Branch office. This practice existed throughout the industry. IBM's unbundling is widely credited with leading to the growth of the software industry.[134][135][136][137] After the unbundling, IBM software was divided into two main categories: System Control Programming (SCP), which remained free to customers, and Program Products (PP), which were charged for. This transformed the customer's value proposition for computer solutions, giving a significant monetary value to something that had hitherto essentially been free. This helped enable the creation of the software industry. Similarly, IBM services were divided into two categories: general information, which remained free and provided at the discretion of IBM, and on-the-job assistance and training of customer personnel, which were subject to a separate charge and were open to non-IBM customers. This decision vastly expanded the market for independent computing services companies.

The company began four decades of Olympic sponsorship with the 1960 Winter Games in Squaw Valley, California. It became a recognized leader in corporate social responsibility, joining federal equal opportunity programs in 1962, opening an inner-city manufacturing plant in 1968, and creating a minority supplier program. It led efforts to improve data security and protect privacy. It set environmental air/water emissions standards that exceeded those dictated by law and brought all its facilities into compliance with those standards. It opened one of the world's most advanced research centers in Yorktown, New York. Its international operations grew rapidly, producing more than half of IBM's revenues by the early 1970s and through technology transfer shaping the way governments and businesses operated around the world. Its personnel and technology played an integral role in the space program and landing the first men on the moon in 1969. In that same year, it changed the way it marketed its technology to customers, unbundling hardware from software and services, effectively launching today's multibillion-dollar software and services industry. See unbundling of software and services, below. It was massively profitable, with a nearly fivefold increase in revenues and earnings during the 1960s.

In 1967 Thomas John Watson, Jr., who had succeeded his father as chairman, announced that IBM would open a large-scale manufacturing plant at Boca Raton to produce its System/360 Model 20 midsized computer. On March 16, 1967, a headline in the Boca Raton News[138] announced “IBM to hire 400 by year’s end.” The plan was for IBM to lease facilities to start making computers until the new site could be developed. A few months later, hiring began for assembly and production control trainees. IBM's Juan Rianda moved from Poughkeepsie, New York, to become the first plant manager at IBM's new Boca operations. To design its new campus, IBM commissioned internationally renowned architect Marcel Breuer (1902–1981), who worked closely with American architect Robert Gatje (1927-2018). In September 1967, the Boca team celebrated a milestone, shipping its first IBM System/360 Model 20 to the City of Clearwater – the first computer in its production run. A year later, IBM 1130 Computing Systems were being produced and shipped from the 203 building. By 1969, IBM's Boca workforce had reached 1,000. That employment number grew to around 1,300 in the next year as a Systems Development Engineering Laboratory was added to the division's operations.

Key events[edit]

- 1961: IBM 7030 Stretch. IBM delivers its first 7030 Stretch supercomputer. Stretch falls short of its original design objectives, and is not a commercial success. But it is a visionary product that pioneers numerous revolutionary computing technologies which are soon widely adopted by the computer industry.[139][140]

- 1961: Thomas J. Watson Research Center. IBM moves its research headquarters from Poughkeepsie, NY to Westchester County, NY, opening the Thomas J. Watson Research Center which remains IBM's largest research facility, centering on semiconductors, computer science, physical science, and mathematics. The lab which IBM established at Columbia University in 1945 was closed and moved to the Yorktown Heights laboratory in 1970.[141]

- 1961: IBM Selectric typewriter. IBM introduces the Selectric typewriter product line. Later Selectric models feature memory, giving rise to the concepts of word processing and desktop publishing. The machine won numerous awards for its design and functionality. Selectrics and their descendants eventually captured 75 percent of the United States market for electric typewriters used in business.[142] IBM replaced the Selectric line with the IBM Wheelwriter in 1984 and transferred its typewriter business to the newly formed Lexmark in 1991.[143]

- 1961: Report Program Generator. IBM offers its Report Program Generator, an application that allows IBM 1401 users to produce reports. This capability was widely adopted throughout the industry, becoming a feature offered in subsequent generations of computers. It played an important role in the successful introduction of computers into small businesses.[144]

- 1962: Basic beliefs. Drawing on established IBM policies, Thomas J. Watson, Jr., codifies three IBM basic beliefs: respect for the individual, customer service, and excellence.[145]

- 1962: SABRE. Two IBM 7090 mainframes formed the backbone of the SABRE reservation system for American Airlines. As the first airline reservation system to work live over phone lines, SABRE linked high-speed computers and data communications to handle seat inventory and passenger records.[146]

- 1964: IBM System/360. In the most important product announcement in company history to date, IBM introduces the IBM System/360: a new concept in computers which creates a "family" of small to large computers, incorporating IBM Solid Logic Technology (SLT) microelectronics and using the same programming instructions. The concept of a compatible "family" of computers transforms the industry.[147]

- 1964: Word processing. IBM introduces the IBM Magnetic Tape Selectric Typewriter, a product that pioneered the application of magnetic recording devices to typewriting, and gave rise to desktop word processing. Referred to then as "power typing," the feature of revising stored text improved office efficiency by allowing typists to type at "rough draft" speed without the pressure of worrying about mistakes.[148]

- 1964: New corporate headquarters. IBM moves its corporate headquarters from New York City to Armonk, New York.[149]

Versacheck software download

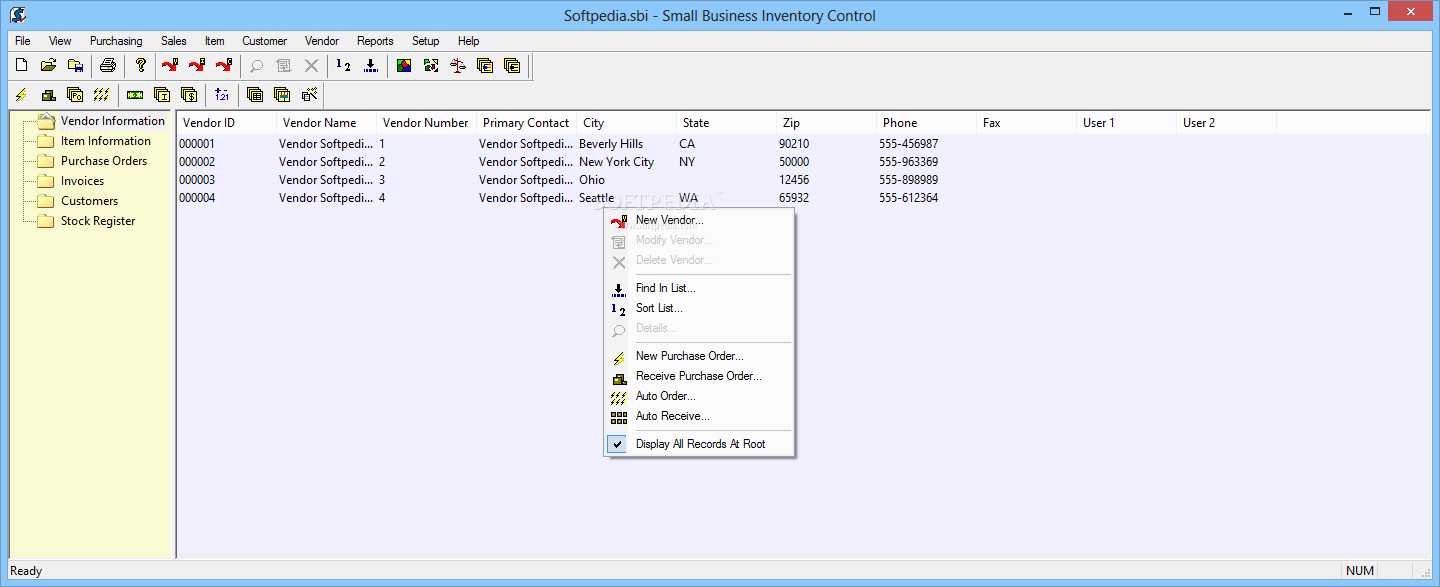

What’s New in the Small Business Inventory Control v3.5 serial key or number?

Screen Shot

System Requirements for Small Business Inventory Control v3.5 serial key or number

- First, download the Small Business Inventory Control v3.5 serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: