A.S.C. Version: 4.1 serial key or number

A.S.C. Version: 4.1 serial key or number

LoggerNet Datalogger Support Software

Note: The following shows notable compatibility information. It is not a comprehensive list of all compatible or incompatible products.

Dataloggers

| Product | Compatible | Note |

|---|---|---|

| 21X(retired) | The 21X requires three PROMs; two PROM 21X Microloggers are not compatible. | |

| CR10(retired) | ||

| CR1000(retired) | ||

| CR1000X | ||

| CR10X(retired) | LoggerNet is compatible with the mixed array, PakBus®, and TD operating systems. | |

| CR200X(retired) | ||

| CR206X(retired) | ||

| CR211X(retired) | ||

| CR216X(retired) | ||

| CR23X(retired) | LoggerNet is compatible with the mixed array, PakBus®, and TD operating systems. | |

| CR295X(retired) | ||

| CR300 | ||

| CR3000 | ||

| CR310 | ||

| CR500(retired) | ||

| CR5000(retired) | ||

| CR510(retired) | LoggerNet is compatible with the mixed array, PakBus®, and TD operating systems. | |

| CR6 | ||

| CR800 | ||

| CR850 | ||

| CR9000(retired) | ||

| CR9000X(retired) |

Distributed Data Acquisition

Additional Compatibility Information

Communications

LoggerNet runs on a PC, using serial ports, telephony drivers, and Ethernet hardware to communicate with data loggers via phone modems, RF devices, and other peripherals.

Software

The development tool of RTMC Pro 1.x and 2.x is not compatible with the RTMC run-time and the standard RTMC development tool in LoggerNet 4. An upgrade for RTMC Pro must be purchased separately.

Computer

LoggerNet is a collection of 32-bit programs designed to run on Intel-based computers running Microsoft Windows operating systems. The recommended minimum computer configuration for running LoggerNet is Windows 7. LoggerNet also runs on Windows 8 and Windows 10. LoggerNet runs on both 32-bit and 64-bit versions of these operating systems.

Other Products

LoggerNet supports most commercially available sensors, SDM devices, multiplexers, relays, vibrating-wire interfaces, ET107, CompactFlash cards, microSD cards, and PC cards.

EA's Revision History Version 4.x

This section is intended to provide a history of the revisions of EA version 4.51, 4.5, 4.1 and 4.0.

For information relating to the history of other versions, select a version below.

Enterprise Architect Version 4.51

Changes and fixes for Version 4.51 - build 751

Fixed display of UML Pattern folders in Resource Tree, now sorted alphabetically |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.51 - build 750

Updated Automation Interface to allow XMI Type specification from Project.ExportPackageXMI() call Added <<invokes>> and <<precedes>> connectors for Iconix Use Case toolbox. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.51 - build 749

Fixed issue where messages with sequence numbers were incorrectly generated in RTF document format. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.51 - build 748

Automation additions, deletions and modifications of terms, tasks and project issues are now reflected in user interface. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.51 - build 747

Enabled outlining (collapsible sections) of source code editor for major languages Code Template Updates: |

Enterprise Architect Version 4.5

Changes and fixes for Version 4.5 - build 744

Fix to include test cases in the Testing Documentation for the root package the command is invoked on. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.5 - build 743

Fix issue with Oracle in countries using, as decimal separator - affected attribute and operation dialog. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.5 - build 742

Fix for critical issue with Oracle repository that could adversely affect a number of functions, particularly security and element features. |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.5 - build 741

Fixed issues when using Ctrl + Arrow keys to move elements in the project tree up or down the order Data Modelling: |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.5 - build 740

Updated application "look and feel" UI components. Data Modelling: Code Template Updates: |

Enterprise Architect Version 4.1

Changes and fixes for Version 4.1 - build 739

Removed Tagged Values tab page from Element, Attribute, Operation and Connector dialogs. All tagged values should be added and edited using the dockable Tagged Values Window (View/Other Windows/Tagged Values) |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.1 - build 738

Further improvements and enhancements to docked tag values window Code Template Updates: |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.1 - build 737

Added dockable Tagged Properties window. Provides the ability to quickly view and edit tagged values (custom properties) for: Automation Interface changes: Added diagrams, attributes, operations and connectors to the dockable Notes window. Now it is possible to edit notes for these elements without invoking their property window New substitution macros available in code templates: Code Template Updates: |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.1 - build 736

Fixed bug with State elements when selected in diagram and having no inplace feature highlighted, could cause crash when accessing main Element menu |

Changes and fixes for Version 4.1 - build 735

Major update to EA diagram functionality to allow inplace editing and selection of many internal element features: 1. Element Name. Generally allow selection and editing of name within diagram element Other changes: |

High Performance MySQL by Jeremy D. Zawodny, Derek J. Balling

Indexes allow MySQL to quickly find and retrieve a set of records from the millions or even billions that a table may contain. If you’ve been using MySQL for any length of time, you’ve probably created indexes in the hopes of getting lighting-quick answers to your queries. And you’ve probably been surprised to find that MySQL didn’t always use the index you thought it would.

For many users, indexes are something of a black art. Sometimes they work wonders, and other times they seem just to slow down inserts and get in the way. And then there are the times when they work fine for a while, then begin to slowly degrade.

In this chapter, we’ll begin by looking at some of the concepts behind indexing and the various types of indexes MySQL provides. From there, we’ll cover some of the specifics in MySQL’s implementation of indexes. The chapter concludes with recommendations for selecting columns to index and the longer term care and feeding of your indexes.

To understand how MySQL uses indexes, it’s best first to understand the basic workings and features of indexes. Once you have a basic understanding of their characteristics, you can start to make more intelligent choices about the right way to use them.

To understand what indexes allow MySQL to do, it’s best to think about how MySQL works to answer a query. Imagine that is a table containing an aggregate phone book for the state of California, with roughly 35 million entries. And keep in mind that records within tables aren’t inherently sorted. Consider a query like this one:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name = 'Zawodny'Without any sort of index to consult, MySQL must read all the records in the table and compare the field with the string “Zawodny” to see whether they match. Clearly that’s not efficient. As the number of records increases, so does the effort necessary to find a given record. In computer science, we call that an O(n) problem.

But given a real phone book, we all know how to quickly locate anyone named Zawodny: flip to the Zs at the back of book and start there. Since the second letter is “a,” we know that any matches will be at or near the front of the list of all names starting with Z. The method used is based on knowledge of the data and how it is sorted.

That’s cheating, isn’t it? Not at all. The reason you can find the Zawodnys so quickly is that they’re sorted alphabetically by last name. So it’s easy to find them, provided you know your ABCs, of course.

Most technical books (like this one) provide an index at the back. It allows you to find the location of important terms and concepts quickly because they’re listed in sorted order along with the corresponding page numbers. Need to know where mysqlhotcopy is discussed? Just look up the page number in the index.

Database indexes are similar. Just as the book author or publisher may choose to create an index of the important concepts and terms in the book, you can choose to create an index on a particular column of a database table. Using the previous example, you might create an index on the last name to make looking up phone numbers faster:

ALTER TABLE phone_book ADD INDEX (last_name)In doing so, you’re asking MySQL to create an ordered list of all the last names in the table. Along with each name, it notes the positions of the matching records—just as the index at the back of this book lists page numbers for each entry.[1]

From the database server’s point of view, indexes exist so that the database can quickly eliminate possible rows from the result set when executing a query. Without any indexes, MySQL (like any database server) must examine every row in a table. Not only is that time consuming, it uses a lot of disk I/O and can effectively pollute the disk cache.

In the real world, it’s rare to find dynamic data that just happens to be sorted (and stays sorted). Books are a special case; they tend to remain static.

Because MySQL needs to maintain a separate list of indexes’ values and keep them updated as your data changes, you really don’t want to index every column in a table. Indexes are a trade-off between space and time. You’re sacrificing some extra disk space and a bit of CPU overhead on each , , and query to make most (if not all) your queries much faster.

Much of the MySQL documentation uses the terms index and key interchangeably. Saying that is a key in the table is the same as saying that the field of the table is indexed.

Indexes trade space for performance. But sometimes you’d rather not trade too much space for the performance you’re after. Luckily, MySQL gives you a lot of control over how much space is used by the indexes. Maybe you have a table with 2 billion rows in it. Adding an index on will require a lot of space. If the average is 8 bytes long, you’re looking at roughly 16 GB of space for the data portion of the index; the row pointers are there no matter what you do, and they add another 4-8 bytes per record.[2]

Instead of indexing the entire last name, you might index only the first 4 bytes:

ALTER TABLE phone_book ADD INDEX (last_name(4))In doing so, you’ve reduced the space requirements for the data portion of the index by roughly half. The trade-off is that MySQL can’t eliminate quite as many rows using this index. A query such as:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name = 'Smith'retrieves all fields beginning with , including all people with name , , and so on. The query must then discard and all other irrelevant rows.

Like many relational database engines, MySQL allows you to create indexes that are composed of multiple columns:

ALTER TABLE phone_book ADD INDEX (last_name, first_name)Such indexes can improve the query speed if you often query all columns together in the clause or if a single column doesn’t have sufficient variety. Of course, you can use partial indexes to reduce the space required:

ALTER TABLE phone_book ADD INDEX (last_name(4), first_name(4))In either case, a query to find Josh Woodward executes quickly:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name = 'Woodward' AND first_name = 'Josh'Having the last name and first name indexed together means that MySQL can eliminate rows based on both fields, thereby greatly reducing the number of rows it must consider. After all, there are a lot more people in the phone book whose last name starts with “Wood” than there are folks whose last name starts with “Wood” and whose first name also starts with “Josh.”

When discussing multicolumn indexes, you may see the individual indexed columns referred to as key parts or “parts of the key.” Multicolumn indexes are also referred to as composite indexes or compound indexes.

So why not just create two indexes, one on and one on ? You could do that, but MySQL won’t use them both at the same time. In fact, MySQL will only ever use one index per table per query—except for s.[3] This fact is important enough to say again: MySQL will only ever use one index per table per query.

With separate indexes on and , MySQL will choose one or the other. It does so by making an educated guess about which index allows it to match fewer rows. We call it an educated guess because MySQL keeps track of some index statistics that allow it to infer what the data looks like. The statistics, of course, are generalizations. While they often let MySQL make smart decisions, if you have very clumpy data, MySQL may make suboptimal choices about index use. We call data clumpy if the key being indexed is sparse in some areas (such as names beginning with X) and highly concentrated in others (such as the name in English-speaking countries). This is an important topic that we’ll revisit later in this book.

How does MySQL order values in the index? If you’ve used another RDBMS, you might expect MySQL to have syntax for specifying that an index be sorted in ascending, descending, or some other order. MySQL gives you no control over its internal sorting of index values. It has little reason to. As of Version 4.0, it does a good job of optimizing cases that cause slower performance for other database systems.

For example, some database products may execute this query quickly:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name = 'Zawodny' ORDER BY first_name DESCAnd this query slowly:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name = 'Zawodny' ORDER BY first_name ASCWhy? Because some databases store the indexes in descending order and are optimized for reading them in that order. In the first case, the database uses the multicolumn index to locate all the matching records. Since the records are already stored in descending order, there’s no need to sort them. But in the second case, the server finds all matching records and then performs a second pass over those rows to sort them.

MySQL is smart enough to “traverse the index backwards” when necessary. It will execute both queries very quickly. In neither case does it need to sort the records.

Indexes aren’t always used to locate matching rows for a query. A unique index specifies that a particular value may only appear once in a given column.[4] In the phone book example, you might create a unique index on to ensure that each phone number appears only once: [5]

ALTER TABLE phone_book ADD UNIQUE (phone_number)The unique index serves a dual purpose. It functions just like any other index when you perform a query based on a phone number:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE phone_number = '555-7271'However, it also checks every value when attempting to insert or update a record to ensure that the value doesn’t already exist. In this way, the unique index acts as a constraint.

Unique indexes use as much space as nonunique indexes do. The value of every column as well as the record’s location is stored. This can be a waste if you use the unique index as a constraint and never as an index. Put another way, you may rely on the unique index to enforce uniqueness but never write a query that uses the unique value. In this case, there’s no need for MySQL to store the locations of every record in the index: you’ll never use them.

Unfortunately, there’s no way to signal your intentions to MySQL. In the future, we’ll likely find a feature introduced for this specific case. The MyISAM storage engine already has support for unique columns without an index (it uses a hash-based system), but the mechanism isn’t exposed at the SQL level yet.

Clustered and secondary indexes

With MyISAM tables, the indexes are kept in a completely separate file that contains a list of primary (and possibly secondary) keys and a value that represents the byte offset for the record. These ensure MySQL can find and then quickly skip to that point within the database to locate the record. MySQL has to store the indexes this way because the records are stored in essentially random order.

With clustered indexes, the primary key and the record itself are “clustered” together, and the records are all stored in primary-key order. InnoDB uses clustered indexes. In the Oracle world, clustered indexes are known as "index-organized tables,” which may help you remember the relationship between the primary key and row ordering.

When your data is almost always searched on via its primary key, clustered indexes can make lookups incredibly fast. With a standard MyISAM index, there are two lookups, one to the index, and a second to the table itself via the location specified in the index. With clustered indexes, there’s a single lookup that points directly to the record in question.

Some operations render clustered indexes less effective. For instance, consider when a secondary index is in use. Going back to our phone book example, suppose you have set as the primary index and set as a secondary index, and you perform the following query:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE phone_number = '555-7271'MySQL scans the index to find the entry for , which contains the primary key entry because ’s primary index is the last name. MySQL then skips to the relevant entry in the database itself.

In other words, lookups based on your primary key happen exceedingly fast, and lookups based on secondary indexes happen at essentially the same speed as MyISAM index lookups would.

But under the right (or rather, the wrong) circumstances, the clustered index can actually degrade performance. When you use one together with a secondary index, you have to consider the combined impact on storage. Secondary indexes point to the primary key rather than the row. Therefore, if you index on a very large value and have several secondary indexes, you will end up with many duplicate copies of that primary index, first as the clustered index stored alongside the records themselves, but then again for as many times as you have secondary indexes pointing to those clustered indexes. With a small value as the primary key, this may not be so bad, but if you are using something potentially long, such as a URL, this repeated storage of the primary key on disk may cause storage issues.

Another less common but equally problematic condition happens when the data is altered such that the primary key is changed on a record. This is the most costly function of clustered indexes. A number of things can happen to make this operation a more severe performance hit:

Alter the record in question according to the query that was issued.

Determine the new primary key for that record, based on the altered data record.

Relocate the stored records so that the record in question is moved to the proper location in the tablespace.

Update any secondary indexes that point to that primary key.

As you might imagine, if you’re altering the primary key for a number of records, that command might take quite some time to do its job, especially on larger tables. Choose your primary keys wisely. Use values that are unlikely to change, such as a Social Security account number instead of a last name, serial number instead of a product name, and so on.

Unique indexes versus primary keys

If you’re coming from other relational databases, you might wonder what the difference between a primary key and a unique index is in MySQL. As usual, it depends. In MyISAM tables, there’s almost no difference. The only thing special about a primary key is that it can’t contain NULL values. The primary key is simply a named . MyISAM tables don’t require that you declare a primary key.

InnoDB and BDB tables require primary keys for every table. There’s no requirement that you specify one, however. If you don’t, the storage engine automatically adds a hidden primary key for you. In both cases, the primary keys are simply incrementing numeric values, similar to an column. If you decide to add your own primary key at a later time, simply use to add one. Both storage engines will discard their internally generated keys in favor of yours. Heap tables don’t require a primary key but will create one for you. In fact, you can create Heap tables with no indexes at all.

It is often difficult to remember that SQL uses tristate logic when performing logical operations. Unless a column is declared , there are three possible outcomes in a logical comparison. The comparison may be true because the values are equivalent; it may be false because the values aren’t equivalent; or it may not match because one of the values is NULL. Whenever one of the values is NULL, the outcome is also NULL.

Programmers often think of NULL as undefined or unknown. It’s a way of telling the database server “an unknown value goes here.” So how do NULL values affect indexes?

NULL values may be used in normal (nonunique) indexes. This is true of all database servers. However, unlike many database servers, MySQL allows you to use NULL values in unique indexes.[6] You can store as many NULL values as you’d like in such an index. This may seem a bit counterintuitive, but that’s the nature of NULL. Because NULL represents an undefined value, MySQL needs to assert that all NULL values are the same if it allowed only a single value in a unique index.

To make things just a bit more interesting, a NULL value may appear only once as a primary key. Why? The SQL standard dictates this behavior. It is one of the few ways in which primary keys are different from unique indexes in MySQL. And, in case you’re wondering, allowing NULL values in the index really doesn’t impact performance.

Having covered some of the basic ideas behind indexing, let’s turn to the various types (or structures) of indexes in MySQL. None of the index types are specific to MySQL. You’ll find similar indexes in PostgreSQL, DB2, Oracle, etc.

Rather than focus too much on the implementation details,[7] we’ll look at the types of data or applications each type was designed to handle and find answers to questions like these: Which index types are the fastest? Most flexible? Use the most or least space?

If this were a general-purpose textbook for a computer science class, we might delve deeper into the specific data structures and algorithms that are employed under the hood. Instead, we’ll try to limit our scope to the practical. If you’re especially curious about the under-the-hood magic, there are plenty of excellent computer science books available on the topic.

The B-tree, or balanced tree, is the most common types of index. Virtually all database servers and embedded database libraries offer B-tree indexes, often as the default index type. They are usually the default because of their unique combination of flexibility, size, and overall good performance.

As the name implies, a B-tree is a tree structure. The nodes are arranged in sorted order based on the key values. A B-tree is said to be balanced because it will never become lopsided as new nodes are added and removed. The main benefit of this balance is that the worst-case performance of a B-tree is always quite good. B-trees offer O(log n) performance for single-record lookups. Unlike binary trees, in which each node has at most two children, B-trees have many keys per node and don’t grow “tall” or “deep” as quickly as a binary tree.

B-tree indexes offer a lot of flexibility when you need to resolve queries. Range-base queries such as the following can be resolved very quickly:

SELECT * FROM phone_book WHERE last_name BETWEEN 'Marten' and 'Mason'The server simply finds the first “Marten” record and the last “Mason” record. It then knows that everything in between are also matches. The same is true of virtually any query that involves understanding the range of values, including and and even an open-ended range query such as the following:

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM phone_book WHERE last_name > 'Zawodny'MySQL will simply find the last Zawodny and count all the records beyond it in the index tree.

The second most popular indexes are hash-based. These hash indexes resemble a hash table rather than a tree. The structure is very flat compared to a tree. Rather than ordering index records based on a comparison of the key value with similar key values, hash indexes are based on the result of running each key through a hash function. The hash function’s job is to generate a semiunique hash value (usually numeric) for any given key. That value is then used to determine which bucket to put the key in.

Consider a common hashing function such as . Given similar strings as input, it produces wildly different results:

mysql> +----------------------------------+ | MD5('Smith') | +----------------------------------+ | e95f770ac4fb91ac2e4873e4b2dfc0e6 | +----------------------------------+ 1 row in set (0.46 sec) mysql> +----------------------------------+ | MD5('Smitty') | +----------------------------------+ | 6d6f09a116b2eded33b9c871e6797a47 | +----------------------------------+ 1 row in set (0.00 sec)However, the MD5 algorithm produces 128-bit values (represented as base-64 by default), which means there are just over 3.4 × 1038 possible values. Because most computers don’t have nearly enough disk space (let alone memory) to contain that many slots, hash tables are always governed by the available storage space.

A common technique that reduces the possible key space of the hash table is to allocate a fixed number of buckets, often a relatively large prime number such as 35,149. You then divide the result of the hash function by the prime number and use the remainder to determine which bucket the value falls into.

That’s the theory. The implementation details, again, can be quite a bit more complex, and knowing them tends not to help much. The end result is that the hash index provides very fast lookups, generally O(1) unless you’re dealing with a hash function that doesn’t produce a good spread of values for your particular data.

While hash-based indexes generally provide some of the fastest key lookups, they are also less flexible and less predictable than other indexes. They’re less flexible because range-based queries can’t use the index. Good hash functions generate very different values for similar values, so the server can’t make any assumptions about the ordering of the data within the index structure. Records that are near each other in the hash table are rarely similar. Hash indexes are less predictable because the wrong combination of data and hash function can result in a hash table in which most of the records are clumped into just a few buckets. When that happens, performance suffers quite a bit. Rather than sifting through a relatively small list of keys that share the same hash value, the computer must examine a large list.

Hash indexes work relatively well for most text and numeric data types. Because hash functions effectively reduce arbitrarily sized keys to a small hash value, they tend not to use as much space as many tree-based indexes.

R-tree indexes are used for spatial or N-dimensional data. They are quite popular in mapping and geoscience applications but work equally well in other situations in which records are often queried based on two axes or dimensions: length and width, height and weight, etc.

Having been added for Version 4.1, R-tree indexes are relatively new to MySQL. MySQL’s implementation is based on the OpenGIS specifications, available online at http://www.opengis.org/. The spatial data support in other popular database servers is often based on the OpenGIS specifications, so the syntax should be familiar if you’ve similar products.

Spatial indexes may be unfamiliar to many long-time MySQL users, so let’s look at a simple example. We’ll create a table to contain spatial data, add several points using X, Y coordinates, and ask MySQL which points fall within the bounds of some polygons.

First, create the table with a small field to contain the spatial data:

mysql> -> ( -> -> -> -> Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec)Then add some points:

mysql> Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql> Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec) mysql> Query OK, 1 row affected (0.00 sec)Now, ensure that it looks right in the table:

mysql> select name, AsText(loc) from map_test; +---------+-------------+ | name | AsText(loc) | +---------+-------------+ | One Two | POINT(1 2) | | Two Two | POINT(2 2) | | Two One | POINT(2 1) | +---------+-------------+ 3 rows in set (0.00 sec)Finally, ask MySQL which points fall within a polygon:

mysql> -> +---------+ | name | +---------+ | One Two | | Two Two | | Two One | +---------+ 3 rows in set (0.00 sec)Figure 4-1 shows the points and polygon on a graph.

MySQL indexes the various shapes that can be represented (points, lines, polygons) using the shape’s minimum bounding rectangle (MBR). To do so, it computes the smallest rectangle you can draw that completely contains the shape. MySQL stores the coordinates of that rectangle and uses them when trying to find shapes in a given area.

Now that we have discussed the common index types, terminology, and uses in relatively generic terms so far, let’s look at the indexes implemented in each of MySQL’s storage engines. Each engine implements a subset of the three index types we’ve looked at. They also provide different optimizations that you should be aware of.

MySQL’s default table type provides B-tree indexes, and as of Version 4.1.0, it provides R-tree indexes for spatial data. In addition to the standard benefits that come with a good B-tree implementation, MyISAM adds two other important but relatively unknown features prefix compression and packed keys.

Prefix compression is used to factor out common prefixes in string keys. In a table that stores URLs, it would be a waste of space for MySQL to store the “http://” in every node of the B-tree. Because it is common to large number of the keys, it will compress the common prefix so that it takes significantly less space.

Packed keys are best thought of as prefix compression for integer keys. Because integer keys are stored with their high bytes first, it’s common for a large group of keys to share a common prefix because the highest bits of the number change far less often. To enable packed keys, simply append:

PACK_KEYS = 1to the CREATETABLE statement.

MySQL stores the indexes for a table in the table’s .MYI file.

One performance-enhancing feature of MyISAM tables is the ability to delay the writing of index data to disk. Normally, MySQL will flush modified key blocks to disk immediately after making changes to them, but you can override this behavior on a per-table basis or globally. Doing so provides a significant performance boost during heavy , , and activity.

MySQL’s tristate setting controls this behavior. The default, , means that MySQL will honor the option in . Setting it to means that MySQL will never delay key writes. And setting it to tells MySQL to delay key writes on all MyISAM tables regardless of the used when the table was created.

The downside of delayed key writes is that the indexes may be out of sync with the data if MySQL crashes and has unwritten data in its key buffer. A , which rebuilds all indexes and may consume a lot of time, is necessary to correct the problem.

MySQL’s only in-memory table type was originally built with support just for hash indexes. As of Version 4.1.0, however, you may choose between B-tree and hash indexes in Heap tables. The default is still to use a hash index, but specifying B-tree is simple:

mysql> -> name varchar(50) not null, -> index using btree (name) -> ) type = HEAP; Query OK, 0 rows affected (0.00 sec)To verify that the index was created properly, use the SHOW KEYS command:

mysql> *************************** 1. row *************************** Table: heap_test Non_unique: 1 Key_name: name Seq_in_index: 1 Column_name: name Collation: A Cardinality: NULL Sub_part: NULL Packed: NULL Null: Index_type: BTREE Comment: 1 row in set (0.00 sec)By combining the flexibility of B-tree indexes and the raw speed of an in-memory table, query performance of the temp tables is hard to beat. Of course, if all you need are fast single-key lookups, the default hash indexes in Heap tables will serve you well. They are lightning fast and very space efficient.

The index data for Heap tables is always stored in memory—just like the data.

MySQL’s Berkeley DB (BDB) tables provide only B-tree indexes. This may come as a surprise to long-time BDB users who may be familiar with its underlying hash-based indexes. The indexes are stored in the same file as the data itself.

BDB’s indexes, like those in MyISAM, also provide prefix compression. Like InnoDB, BDB also uses clustered indexes, and BDB tables require a primary key. If you don’t supply one, MySQL creates a hidden primary key it uses internally for locating rows. The requirement exists because BDB always uses the primary key to locate rows. Index entries always refer to rows using the primary key rather than the record’s physical location. This means that record lookups on secondary indexes are slightly slower then primary-key lookups.

InnoDB tables provide B-tree indexes. The indexes provide no packing or prefix compression. In addition, InnoDB also requires a primary key for each table. As with BDB, though, if you don’t provide a primary key, MySQL will supply a 64-bit value for you.

The indexes are stored in the InnoDB tablespace, just like the data and data dictionary (table definitions, etc.). Furthermore, InnoDB uses clustered indexes. That is, the primary key’s value directly affects the physical location of the row as well as its corresponding index node. Because of this, lookups based on primary key in InnoDB are very fast. Once the index node is found, the relevant records are likely to already be cached in InnoDB’s buffer pool.

A full-text index is a special type of index that can quickly retrieve the locations of every distinct word in a field. MySQL’s provides full-text indexing support in MyISAM tables. Full-text indexes are built against one or more text fields (, , etc.) in a table.

The full-text index is also stored in a table’s .MYI file. It is implemented by creating a normal two-part MyISAM B-tree index in which the first field is a , and the second is a . The first field contains the indexed word, and the is its local weight in the row.

Because they generally contain one record for each word in each indexed field, full-text indexes can get large rather quickly. Luckily, MySQL’s B-tree indexes are quite efficient, so space consumed by full-text is well worth the performance boost.

It’s not uncommon for a query like:

select * from articles where body = "%database%"to run thousands of times faster when a full-text index is added and the query is re-written as:

select * from articles (body) match against ('database')As with all index types, it’s a matter of trading space for speed.

There are many times when MySQL simply can’t use an index to satisfy a query. To help you recognize these limitations (and hopefully avoid them), let’s look at the four main impediments to using an index.

A query to locate all records that contain the word “buffy”:

select * from pages where page_text like "%buffy%"is bound to be slow. It requires MySQL to scan every row in the table. And it won’t even find all occurrences, because “buffy” may be followed by some form of punctuation. The solution, of course, is to build a full-text index on the field and query using MySQL’s syntax.

When you’re dealing with partial words, however, things degenerate quickly. Imagine trying to find the phone number for everyone whose last name contains the string “son”, such as Johnson, Ansona, or Bronson. That query would look like this:

select phone_number from phone_book where last_name like "%son%"That seems suspiciously similar to the “buffy” example, and it is. Because you are performing a wildcard search on the field, MySQL will need to read every row, but switching to a full-text index won’t help. Full-text indexes deal with complete words, so they’re of no help in this situation.

If that’s surprising, consider how you’d attempt to locate all those names in a normal phone book. Can you think of an efficient approach? There’s really no simple change that can be made to the printed phone book that will facilitate this type of query.

Using a regular expression has similar problems. Imagine trying to find all last names that end with either “ith,” such as Smith, or “son” as in Johnson. As any Perl hacker would tell you, that’s easy. Build a regular expression that looks something like .

Translating that into MySQL, you might write this query:

select last_name from phone_book where last_name rlike "(son|ith)$"However, you’d find that it runs slowly, and it does so for the same reasons that wildcard searches are slow. There’s simply no generalized and efficient way to build an index that facilitates running arbitrary wildcard or regular-expression searches.

In this specific case, you can work around this limitation by storing reversed last names in a second field. Then you can reverse the sense of the search and use a query like this:

select last_name from phone_book where rev_last_name like "thi%" union select last_name from phone_book where rev_last_name like "nos%"But that’s efficient only because you’re starting at the beginning of the string, which is really the end of the real string before it is reversed. Again, there’s no general solution to this problem.

Note that a regular expression still isn’t efficient in this case. You might be tempted to write this query:

select last_name from phone_book where rev_last_name rlike "^(thi|nos)"You would be disappointed by its performance. The MySQL optimizer simply never tries to optimize regex-based queries.

Poor statistics or corruption

If MySQL’s internal index statistics become corrupted or otherwise incorrect (possibly as the result of a crash or accidental server shutdown), MySQL may begin to exhibit very strange behavior. If the statistics are simply wrong, you may find that it no longer uses an index for your query. Or it may use an index only some of the time.

What’s likely happened is that MySQL believes that the number of rows that match your query is so high that it would actually be more efficient to perform a full table scan. Because table scans are primarily sequential reads, they’re faster than reading a large percentage of the records using an index, which requires far more disk seeks.

If this happens (or you suspect it has), try the index repair and analysis commands explained in the “Index Maintenance” section later in this chapter.

Similarly, if a table actually does have too many rows that really do match your query, performance can be quite slow. How many rows are too many for MySQL? It depends. But a good rule of thumb is that when MySQL believes more than about 30% of the rows are likely matches, it will resort to a table scan rather than using the index. There are a few exceptions to this rule. You’ll find a more detailed discussion of this problem in Chapter 5.

Once you’re done adding and dropping indexes, and your application is running happily, you may wonder about any ongoing index maintenance and administrative tasks. The good news is that there’s no requirement that you do anything special, but there are a couple of things you may want to do from time to time.

Obtaining Index Information

If you’re ever asked to help debug a slow query or indexing problem against a table (or group of tables) that you haven’t seen in quite a while, you’ll need to recover some basic information. Which columns are indexed? How many values are there? How large is the index?

Luckily, MySQL makes it relatively easy to gather this information. By using , you can retrieve the complete SQL necessary to (re-)create the table. However, if you care only about indexes, provides a lot more information.

mysql> *************************** 1. row *************************** Table: access_jeremy_zawodny_com Non_unique: 1 Key_name: time_stamp Seq_in_index: 1 Column_name: time_stamp Collation: A Cardinality: 9434851 Sub_part: NULL Packed: NULL Null: YES Index_type: BTREE Comment: 1 rows in set (0.00 sec)You may substitute for in the query.

The table in the example has a single index named . It is a B-tree index with only one component, the column (as opposed to a multicolumn index). The index isn’t packed and is allowed to contain NULL values. It’s a non-unique index, so duplicates are allowed.

Refreshing Index Statistics

Over time, a table that sees many changes is likely to develop some inefficiencies in its indexes. Fragmentation due to blocks moving around on disk and inaccurate index statistics are the two most common problems you’re likely to see. Luckily, it’s easy for MySQL to optimize index data for MyISAM tables.

You can use the command to reindex a table. In doing so, MySQL will reread all the records in the table and reconstruct all of its indexes. The result will be tightly packed indexes with good statistics available.

Keep in mind that reindexing the table can take quite a bit of time if the table is large. During that time, MySQL has a write lock on the table, so data can’t be updated.

Using the myisamchk command-line tool, you can perform the analysis offline:

$ database-name $ table-nameJust be sure that MySQL isn’t running when you try this, or you run the risk of corrupting your indexes.

BDB and InnoDB tables are less likely to need this sort of tuning. That’s a good thing, because the only ways to reindex them are a bit more time consuming. You can manually drop and re-create all the indexes, or you have to dump and reload the tables. However, using on an InnoDB table causes InnoDB to re-sample the data in an attempt to collect better statistics.

What’s New in the A.S.C. Version: 4.1 serial key or number?

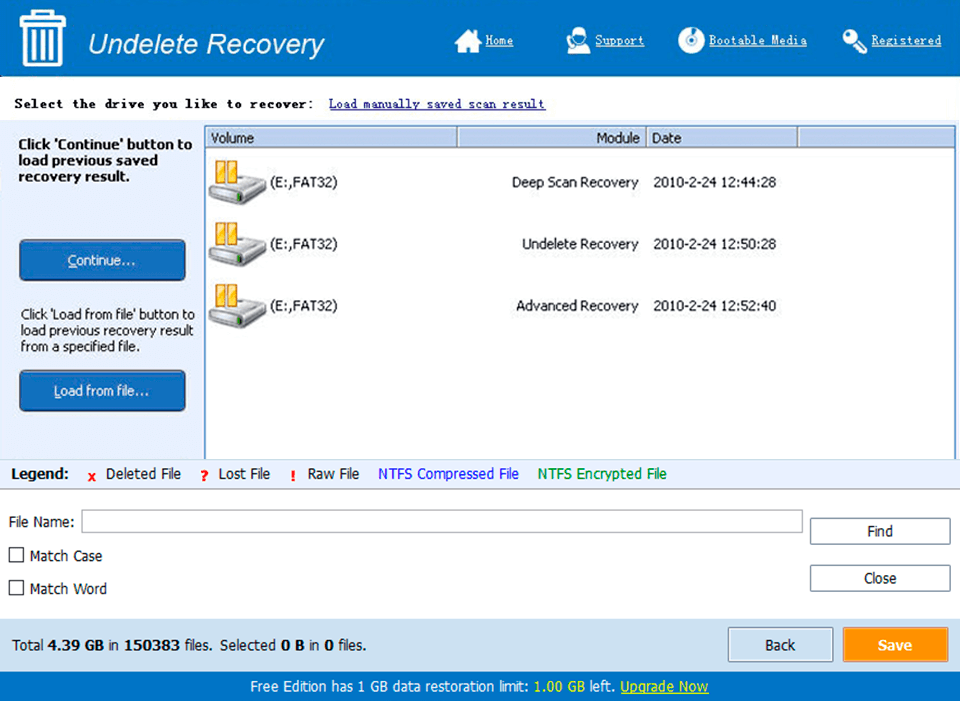

Screen Shot

System Requirements for A.S.C. Version: 4.1 serial key or number

- First, download the A.S.C. Version: 4.1 serial key or number

-

You can download its setup from given links: