Summer Season v1.0 serial key or number

Summer Season v1.0 serial key or number

BIOLOGICAL AND APPLIED SCIENCES

Seasonal changes in the distribution and abundance of marine cladocerans of the Northwest Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean), Spain

Christiane Sampaio de SouzaI,*; Paulo Mafalda Jr.I; Soluna SallésII; Teodoro RamirezII; Dolores CortésII; Alberto GarciaII; Jesus MercadoII; Manuel Vargas-YañezII

IInstituto de Biologia; Universidade Federal da Bahia; 40210-020; Salvador - BA - Brasil

IICentro Oceanográfico de Málaga Fuengirola; Instituto Español de Oceanografía Muelle Pesquero, s/n; 29640; Fuengirola - Málaga - España

ABSTRACT

The annual cycle of marine cladocerans was studied over six years from 1994 to 1999 within the frame of the monitoring Project ECOMALAGA at a nine stations in the NW of the Alboran Sea, with the aim of assessing seasonal patterns and interannual trends in distribution and abundance of marine cladocerans. Seven species (Penilia avirostris, Evadne nordmanni, Evadne spinifera, Pseudoevadne tergestina, Pleopis polyphemoides, Podon leuckarti and Podon intermedius) were detected in the northwest Alboran Sea. Total cladoceran relative abundance varied from 0 to 89 % of the total cladocerans. The abundance of cladocerans was higher in summer-autumn than in winter-spring (7012 – 4711.100 and 743 – 217.100m-3 , respectively). The species composition was very different in terms of seasonality. P. polyphemoides, P. leuckarti and P. intermedius appeared mostly during the spring. P. tergestina, E. spinifera and E. nordmanni predominantly occurred during the winter. P. avirostris occurred mostly during the summer and autumn.

Key words: Alboran Sea, marine cladocerans, distribution and abundance

INTRODUCTION

Only eight species of cladocerans have been known to be distributed in the world oceans. Most marine cladocerans are restricted to coastal waters, where they make up a significant part of the zooplanktonic community at given periods. This confers on these animals a major trophodynamic role, as they can be an important food item for carnivorous zooplankton, as well as pelagic fish and their larvae (Cheng and Chao, 1982). Despite their high densities, marine cladocerans may disappear from the plankton during certain seasons of the year, which in temperate regions is generally in winter (Onbé, 1974, 1978, 1985; Ramirez and Perez Seijas, 1985).

In temperate, subtropical and tropical seas, they comprise significant portions of the local zooplankton community, usually represented by Penilia avirostris and Pseudoevadne tergestina. However, other species such as Evadne nordmanni and Podon leuckarti, if present, appear at low densities only in low temperature months, and are regarded as cold-water species (Onbé et al. 1996). For instance, in temperate and tropical ecosystems, marine cladocerans are the dominant zooplankters of summer communities in coastal waters, when the water stability increases and prokaryotic picoplankton comprise much of the primary producers biomass (Onbé 1985; Calbet et al. 2001). In the coastal NW Mediterranean, during summer the cladoceran Penilia avirostris shares its dominance on the zooplanktonic community (Calbet et al. 2001). These groups of organisms are cosmopolitan and occur commonly in nearshore (Onbé 1985; Wong et al. 1992; Calbet et al. 2001).

Despite their high seasonal abundance and role in marine systems, cladocerans have been little studied compared to copepods, and the reasons for their explosive community growth are still unknown. Therefore, the present study characterized the cladoceran community of the Northwest Alboran Sea (Western Mediterranean) and evaluated its distribution and abundance in order to assess the seasonal cycles and detect possible temporal trends.

Study Area

The study area was delimited to the north by the coast malagueña; to the west by Cabo Pino (4º44' 53W), and to the east by the Caleta de Vélez (4º03' 90W). The northwestern sector of the Alboran Sea is a favourable reproductive habitat, as well as a nursery ground (García et al., 1988; Rodríguez, 1990). The Atlantic jet which penetrates through the Strait of Gibraltar (Parrilla and Kinder, 1987) produces a system of two anticyclonic gyres which occupy the central part of the eastern and western basins of the Alboran Sea. According to Rubín et al. (1999), the upwelling of deeper Mediterranean waters enriched in inorganic nutrients is induced by several mechanisms (Parrilla and Kinder, 1987; Sharhan et al., 2000). This enrichment mechanism favours the presence of cores of high phytoplankton and zooplankton abundance (Cortés et al., 1985; Garcıía-Górriz and Carr, 2001; Minas et al., 1991; Ruíz et al., 2001; Rodríguez et al., 1982, 1997). Although this hydrological pattern is maintained during the entire annual cycle, seasonal changes in the water column stratification and intensity of the Atlantic water inflow have been described (García-Lafuente et al., 2000), thereby affecting the strength of upwelling off the Malaga coast (Ramírez et al.,2005). Accordingly, annual peaks of nutrient concentration and chlorophyll-a tend to be detected in spring (Mercado et al., 2006; Ramírez et al., 2006). Souza et al. (2005) have described a seasonal succession pattern for the zooplankton communities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The samples for plankton were collected quarterly data from 1994 to 1999 in nine stations located in three transect (P, Cabo Pino; M, Malaga and V, Caleta de Vélez), whose depths varied between 25 and 500 m. The stations P1, M1 and V1 were located in the coastal area; P2, M2 and V2 were situated in shelf break and P3, M3 and V3 were located in oceanic area (Fig. 1). The surveys were carried out in January–February (winter period), March–April (spring period), June–July (summer period) and October–November (autumn period) on board the RV Odón de Buen. The collections of the 216 samples was done with a Bongo 40 cm of mouth size (200 μm mesh) up to 100 m depth. The nets were equipped with two flowmeters independent to estimate the water volume filtered. Marine cladocerans were identified and counted on a Bogorov plate using a stereoscopic microscope Leica MZ8 from an aliquot obtained by a Folson sub-sampler, the standard densities of the species were expressed as the number per 100 m-3 of filtered water for each collection. The vertical profiles of temperature and salinity were obtained with a Seabird 25 CTD at ach station during all the surveys.

Data analysis

Correspondence Analysis (CA), which represented the species and samples as occurring in a postulated environmental space, or ordination space, was used to explore the seasonal trends of the species of marine cladocerans. The raw abundance data matrix was transformed logarithmically according to log (ni, j + 1), where ni was the abundance of the ith group in the jth sample. The correspondence Analysis (CA) assumes that species have unimodal species response curves. A species is located in that location of space where it is most abundant. Correspondence Analysis was employed for this study using the CANOCO program.

A MRPP (Multi-response Permutation Procedures) analysis was utilised in order to prove the existence of significant differences in the composition of marine cladocerans between the study periods.

RESULTS

Hydrographic condition

The extreme values of temperature were 14.2 and 21.1ºC. The temperature showed an annual variation, with maximums in summer-autumn and minimums in winter and spring (Fig. 2). The data of salinity oscillated between 36.5 and 37.5. Salinity variations also followed a seasonal pattern, with values more elevated in spring and lower in autumn (Fig. 2). During the period of spring-summer was observed stratification in the water column with the termoclina located between 25 and 50 m. However, during the autumn-winter, the water column was mixed. The zones of outcrops were located in the bay of Malaga and radial of Cabo Pino. These events were associated to winds of the west, which pushed the water of the coast towards open sea, giving rise to an inequality in the level of the sea that was compensated with the deep water contribution, cold and rich in nutrients. The Atlantic Water (AW), which penetrates by the Straits of Gibraltar, extends by the Alborán Sea upon the Mediterranean Intermediate Water (MIW). The greater space uniformity of temperature and salinity occurred in the autumn when there was a greater Atlantic water entrance, whereas in spring, the Atlantic water was modified by mixture with Mediterranean water (Mafalda Jr. and Rubín, 2006).

Cladoceran occurrence and composition

Seven cladoceran species were identified: Penilia avirostris Dana, 1849, Pseudoevadne tergestina Claus, 1877, Evadne spinifera P. E. Müller, 1867, Evadne nordmanni Lovén, 1836, Pleopis polyphemoides Leuckart, 1859, Podon leuckartii (G. O. Sars, 1862), Podon intermedius Lilljeborg, 1853. The relative abundance of cladoceran species varied from 0 to 89% of the total cladocerans. The most abundant species was Penilia avirostris, varying from 9 to 89% of the total cladocerans. The higher abundance was observed during the summer and autumn, while winter was lowest abundance. Another abundant species was Evadne nordmanni which varied from 0 to 59%. It was most abundant in winter. Evadne spinifera was more abundant in winter and spring and varied from 4 to 24%. Pseudoevadne tergestina abundance varied from 1 to 6% and showed higher abundance in winter. Pleopis polyphemoides varied 0 to 15%, Podon leuckarti and Podon intermedius varied 0 to 8% with higher abundance observed during spring.

The most frequent species in all the studied samples was Penilia avirostris with 100% during summer and 98% during autumn, followed by Evadne spinifera (83% during summer and 87% during autumn) and Pseudoevadne tergestina (65% during summer and 69% during autumn). Pleopis polyphemoides, Podon leuckarti and Podon intermedius occurred most frequently during spring and summer (52 and 74%; 24 and 35%; 31 and 22% respectively).

The MRPP test showed differences in the composition of marine cladocerans between the study periods (p = 0.0067)

Spatial and temporal distribution of species

All the species of cladocerans were collected in all seasons of the year occurring in coastal, shelf break and oceanic areas of the Alboran sea. Penilia avirostris showed large distribution occurring in all the regions. The maximum density was observed during the summer and autumn in coastal area in all the transects (Fig. 5). Pseudoevadne tergestina, E. spinifera, E. nordmanni, Pleopis polyphemoides and Podon leuckarti too showed the maximum density during the summer and autumn in the coastal area but with less density than P. avirostris. Podon intermedius was found predominantly during the spring in coastal stations in transect V (Fig. 3 and 4).

Seasonal trends of species

The correspondence analyses showed the relationships of cladocerans species and periods in the Northwest Alboran Sea. Axes represent degree of relationship obtained from the analyses, such that proximity and similar location indicate closeness. The eigenvalues for the first two axes were 0.53 and 0.16, respectively. The sum of all the eigenvalues of CA was 0.87. The first four ordination axes of CA cumulatively explained 96% of species variance with the first two axes explaining about 79.4% of the variance. Axis–1 separated the winter stations from the spring and autumn stations. Axis-2 further differentiated the autumn stations and spring stations, denoting seasonal changes in the abundance of marine cladocerans (Fig. 6).

The plot of CA sample and species scores illustrates their dispersion pattern within the first two dimensions of the CA ordination (Fig. 6). Figure 6, showed that, the species composition was very different in terms of seasonality. Pleopis polyphemoides, Podon leuckarti and Podon intermedius were positively correlated with the first CA axes and negatively with the second, appeared mostly during the spring stations. Pseudoevadne tergestina and Evadne spinifera were negatively correlated with the first CA axes and positively with the second, predominantly occurred during the winter stations. Evadne nordmanni was positively correlated with the first and second CA axes, predominantly occurred during the winter stations. Penilia avirostris was negatively correlated with the first and second CA axes, occurred mostly during the summer and autumn stations.

DISCUSSION

The present study revealed seven species of cladocerans, Penilia avirostris, Pseudoevadne tergestina, Evadne spinifera, Evadne nordmanni, Pleopis polyphemoides, Podon leuckarti and Podon intermedius. The species of cladocerans found in the study area was typical of marine environments (Coelho-Botelho et al., 1999; Lopes, 1996; Montú, 1980; Nogueira et al., 1999; Valentin and Marazzo, 2003; Marazzo and Valentin 2004). Penilia avirostris, Pseudoevadne tergestina and E. spinifera are recognised as typical from the warm water. Thus, they are frequently associated (Della Croce and Venugopal, 1972; Onbé, 1974; Ramirez, 1981). P. avirostris is a cosmopolitan species. It is typical of coastal environment and shows high eurihalinity. A few results are found in literature about E.spinifera; this may be due to its rare occurrence and lower abundance in the neritic waters, when compared to other cladoceran species. E. spinifera is more abundant in high-temperature oceanic waters, and has been classified as a typical thermophile and stenohaline species (Gieskes, 1971). Evadne nordmanni has been reported to occur in the oceanic waters in the North Atlantic and the North Sea (Gieskes, 1970, 1971a), the Indian Ocean (Della Croce and Venugopal, 1972) and the northwestern Pacific (Kim, 1989). They usually about in the neritic regions (Onbé 1974; Kim et al., 1989). P. leuckarti is also known to be distributed in neritic waters (Gieskes 1970, 1971b; Onbé and Ikeda 1995).

High abundance of cladocerans recorded in the present study occurred in the coastal region. Penilia avirostris abundance peaks were related during the summer and autumn, these species was shown to prefer less saline and warmer waters which prevailed there at that time. According to Onbé and Ikeda (1995), among the seven species of marine cladocerans occurring in Toyama Bay (southern Japan Sea), Penilia avirostris was one of the important members of the plankton in summer. This species is an important component of the zooplankton in the coastal waters like in the coast off Northwest Alboran Sea in certain periods of the year, along with other species such as Pseudoevadne tergestina and Pleopis polyphemoides and is an important contributor to secondary production. However, Penilia avirostris may disappear from the plankton at certain periods. In Guanabara Bay, Marazzo and Valentin (2001) observed that Penilia avirostris reached its maximum density during the autumn and disappeared in the winter and spring.

The composition, abundance and spatial distribution of the cladocerans in the Northwest Alboran Sea have been related to the seasonal variation pattern in the hydrology.

The most conspicuous temporal variation pattern for the cladocerans abundance was characterised by higher abundances in summer and lower in spring. This seasonal pattern matches the one described for the zooplankton biomass by García and Camiñas (1985) in the northwestern Alboran Sea, although it contrasted with the seasonal variations obtained for other locations at the western basin of the Mediterranean Sea, where lower biomasses were usually found in the summer, and higher values were obtained from April to June (Sabatés et al., 1989; Fernández de Puelles, 1990; Champalbert, 1996).

The composition and abundance of the zooplankton communities can be influenced by several physical, chemical and biological factors (Neves et al., 2003). Temperature can cause changes in the community composition as well as density. All of them are the important factors determining seasonal distribution of marine cladocerans (Marazzo and Valentin, 2004). Other factors such as salinity, dissolved oxygen, tidal currents, can also affect the occurrence and distribution of cladocerans (Valentin and Marazzo, 2003; Marazzo and Valentin, 2004).

Possibly temperature and salinity were directly or indirectly responsible for the seasonal changes in the populations of cladocerans species. An apparent consensus seems to prevail among the researchers that temperature variations are conditioning factors in reproductive changes found in the marine cladocerans in temperate regions. This is because these organisms are very evenly distributed from spring to autumn. But with the start of winter, depressive features are in evidence and, shortly thereafter, the species disappear from the plankton. Undoubtedly, determining the factors depressing for marine cladocerans is of extreme relevance, as these organisms display significant reproductive changes in response to a number of environmental conditions and, thus, these changes may become effective ecological indicators, as has been proposed by Gieskes (1971). Yet, the rare occurrence of some species can be due to the oblique hauls (Pseudoevadne tergestina and Evadne spinifera show preference to surface zone) and/or due to the mesh size chosen (100 µm is recommended instead of 200 µm), which can be too coarse to retain the small species (Onbé, 1999).

In conclusion, the results of this study demonstrated that there were seasonal changes in the distribution and abundance of marine cladocerans of the northwest Alboran Sea in response of hydrological changes.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The monitoring program ECOMÁLAGA could not have been carried out without the technical assistance of many people belonging to the Instituto Español de Oceanografía (Ministerio Español de Educación y Ciencia, MEC) who have collaborated in the surveys and analysis samples.

REFERENCES

Bartual A.; Reul A.; Rodríguez V. (2001), Surface distribution of chlorophyll, particles and gelbstoff in the Atlantic jet of the Alborán Sea: from submesoscale to subinertial scales of variability. J. of Mar. Sys., 29, 277–292. [ Links ]

Bakun A. (1996), Patterns in the Ocean: Ocean Processes and Marine Population Dynamics. San Diego, CA: University of California Sea Grant, in cooperation with Centro de Investigaciones Biológicas del Noroeste, La Paz, Baja California Sur, México, 323pp. [ Links ]

Calbet A.; Garrido S.; Saiz E.; Alcaraz M.; Duarte M. (2001), Annual zooplankton succession in coastal NW Mediterranean waters: the importance of the smaller size fractions. J. Plank. Res., 23, 319–331. [ Links ]

Cortés D.R.; Gil J.; Garcia A. (1985), General distribution of chlorophyll, temperature and salinity in the north-western sector of Alboran Sea. In: Communication from the XXIX Congres-Assemblee pleniere CIESM. Lucerne, pp. 11–19. [ Links ]

Cheng, C. and Chao, W. C. (1982), Studies on the marine Cladocera of China II. Distribution. Acta Oceanol. Sinica. 4, 731-742. [ Links ]

García A.; Cortés D.; Ramírez T. (1998), Daily larval growth and DNA and RNA content of the Northwest Mediterranean anchovy Engraulis encrasicolus and their relation to the environment. Mar. Ecol. Pro. Ser., 166, 237–245. [ Links ]

García-Górriz E. and Carr M. E. (2001), Physical control of phytoplankton distributions in the Alboran Sea: a numerical and satellite approach. J. of Geophy. Res., 106, 16795–16805. [ Links ]

García-Lafuente J.; Vargas J. M.; Candela J.; Bascheck B.; Plaza F.; Sarchan T. (2000).,The tide at the eastern section of the strait of Gibraltar. J. of Geophy. Res., 105 (C6), 14197–14213. [ Links ]

Mafalda P. Jr. and Rubín J. P. (2006), Interannual Variation of Larval Fish Assemblages in the Gulf of Cádiz (SW Iberian Peninsula) in Relation to Summer Oceanographic Conditions. Braz. Arch. of Biol. and Tech., 49 (2), 287-296. [ Links ]

Mercado J. M.; Ramírez T.; Cortés D.; Sebastián M.; Reul A.; Batista B. (2006), Diurnal changes in the bio-optical properties of the phytoplankton in the Alborán Sea (Mediterranean Sea). Est. Coa. and Shelf Sci., 69, 459–470. [ Links ]

Minas H. J.; Coste B.; LeCorre P.; Minas M.; Raimbault P. (1991), Biological and geochemical signatures associated with the water circulation through the Strait of Gibraltar and in western Alboran Sea. J. of Geophy. Res., 96, 8755–8771. [ Links ]

Onbé T. (1974), Studies on the ecology of marine cladocerans. J. Fac. Fish. Anim. Husb. Hiroshima Univ., 13, 83-179. [ Links ]

Onbé T. (1978), Life cycle of marine cladocerans. Bull. Plankton Soc, 25, 41-54. [ Links ]

Onbé T. (1985), Seasonal fluctuations in the abundance of populations of marine cladocerans and their resting eggs in the Inland Sea of Japan. Mar. Biol., 87, 83-88. [ Links ]

Onbé T.; Tanimura A.; Fukuchi M.; Hattori H.; Sasaki H.; Matsuda O. (1996), distribution of marine cladocerans in the northern Bering sea and the Chukchi sea. Proc. NIPR Symp. Polar Biol., 9, 141-152. [ Links ]

Parrilla G. and Kinder T. H. (1987), Oceanografía física del Mar de Alborán. Bol. del Ins. Espanol de Ocean., 4 (1), 133–165. [ Links ]

Ramirez F. C. and Perez Seijas G. M. (1985), New data on the ecological distribution of cladocerans and first local observations on reproduction of Evadne nordmanni and Podon intermedius (Crustacea, Cladocera) in Argentine Sea waters, Physis A, 43, 131-143. [ Links ]

Ramírez T.; Cortés D.; Mercado J. M.; Vargas-Yánez M.; Sebastián M.; Liger E. (2005), Seasonal dynamics of inorganic nutrients and phytoplankton biomass in the NW Alboran Sea. Est.Co. and Shelf Sci., 65, 654–670. [ Links ]

Ramírez T.; Liger E.; Cortés D.; Mercado J. M.; Vargas M.; Sebastián M. (2006), Electron transport system activity in an upwelling area of the NW Alborán Sea. J. of Plankton Res., 65, 654–670. [ Links ]

Rodríguez J. M. (1990), Contribution to the icthyoplankton study in the Alboran Sea. Bol. del Inst. Espanol de Ocean., 6, 1–19. [ Links ]

Rodríguez J.; García A.; Rodríguez V. (1982), Zooplanktonic communities of the divergence zone in the northwestern Alboran Sea. Publi. Staz. Zoo. di Napoli I. [ Links ]

Rodríguez V.; Blanco J. M.; Jiménez-Gómez F.; Rodríguez J.; Echevarría F.; Guerrero F. (1997), Distribución espacial de algunos estimadores de biomasa fitoplanctónica y material orgánico particulado en el mar de Alborán, en condiciones de estratificación térmica (julio de 1993). Mar. Eco., 2, 133–144. [ Links ]

Rubín J. P.; Cano N.; Prieto L.; García M. C.; Ruíz J.; Echevarría A.; Corzo A.; Gálvez J. A.; Lozano F.; Alonso-Santos J. C.; Escánez J.; Juárez A.; Zabala L.; Hernández F.; García Lafuente J.; Vargas M. (1999), La estructura del ecosistema pelágico en relación con las condiciones oceanográficas y topográficas en el golfo de Cádiz, estrecho de Gibraltar y mar de Alborán (sector noroeste), en julio de 1995. Info. Téc. del Inst. Espanol de Ocean., 175, 1–73. [ Links ]

Ruíz J.; Echevarría F.; Font J.; Ruíz S.; García E.; Blanco J. M.; Jiménez-Gómez F.; Prieto L.; González-Alaminos A.; García; C. M.; Cipollini P.; Snaith H.; Bartual A.; Reul A.; Rodríguez V. (2001), Surface distribution of chlorophyll, particles and gelbstoff in the Atlantic jet of the Alborán Sea: from submesoscale to subinertial scales of variability. J. of Mar. Sys., 29, 277–292. [ Links ]

Sabatés A.; Gil J. M.; Pagés F. (1989), Relationship between zooplankton distribution, geographic characteristics and hydrographic patterns off the Catalan coast (Western Mediterranean). Mar. Bio., 3, 153–159. [ Links ]

Sharhan T.; García-Lafuente J.; Vargas M.; Vargas J. M.; Plaza P. (2000), Upwelling mechanisms in the northwestern Alborán Sea. Jour. of Mar. Sys., 23, 317–331. [ Links ]

Souza C.; Mafalda P.; Salles S.; Ramírez T.; Cortés D.; García A.; Mercado J.; Vargas-Yánez M. (2005), Tendencias estaciónales y espaciales en la comunidad mesozoplnactónica en una serie temporal plurianual en el noroeste del Mar de Alborán, Espana. Rev. Bio. Mar. y Ocean., 40 (1), 45–54. [ Links ]

Valentin J. L. and Marazzo A. (2003), Modeling the population dynamics of Penilia avirostris (Branchiopoda, Ctenopoda) in a tropical bay. Acta Oecol., 24, 369-376. [ Links ]

Wong C. K.; Chan A. L. C.; Tang K. W. (1992), Natural ingestion rates and grazing of the marine cladoceran Penilia avirostris Dana in Tolo Harbour, Hong Kong. J. Plankton Res., 14, 1757–1765. [ Links ]

Received: July 30, 2009; Revised: January 11, 2010; Accepted: March 03, 2011

* Author for correspondence: chsampaio@ig.com.br

InfluxDB line protocol tutorial

See the equivalent InfluxDB v2.0 documentation:Line protocol.

The InfluxDB line protocol is a text-based format for writing points to the database. Points must be in line protocol format for InfluxDB to successfully parse and write points (unless you’re using a service plugin).

Using fictional temperature data, this page introduces InfluxDB line protocol. It covers:

The final section, Writing data to InfluxDB, describes how to get data into InfluxDB and how InfluxDB handles Line Protocol duplicates.

Syntax

A single line of text in line protocol format represents one data point in InfluxDB. It informs InfluxDB of the point’s measurement, tag set, field set, and timestamp. The following code block shows a sample of line protocol and breaks it into its individual components:

Moving across each element in the diagram:

Measurement

The name of the measurement that you want to write your data to. The measurement is required in line protocol.

In the example, the measurement name is .

Tag set

The tag(s) that you want to include with your data point. Tags are optional in line protocol.

Note: Avoid using the reserved keys , , and . If reserved keys are included as a tag or field key, the associated point is discarded.

Notice that the measurement and tag set are separated by a comma and no spaces.

Separate tag key-value pairs with an equals sign and no spaces:

Separate multiple tag-value pairs with a comma and no spaces:

In the example, the tag set consists of one tag: . Adding another tag () to the example looks like this:

For best performance you should sort tags by key before sending them to the database. The sort should match the results from the Go bytes.Compare function.

Whitespace I

Separate the measurement and the field set or, if you’re including a tag set with your data point, separate the tag set and the field set with a whitespace. The whitespace is required in line protocol.

Valid line protocol with no tag set:

Field set

The field(s) for your data point. Every data point requires at least one field in line protocol.

Separate field key-value pairs with an equals sign and no spaces:

Separate multiple field-value pairs with a comma and no spaces:

In the example, the field set consists of one field: . Adding another field () to the example looks like this:

Whitespace II

Separate the field set and the optional timestamp with a whitespace. The whitespace is required in line protocol if you’re including a timestamp.

Timestamp

The timestamp for your data point in nanosecond-precision Unix time. The timestamp is optional in line protocol. If you do not specify a timestamp for your data point InfluxDB uses the server’s local nanosecond timestamp in UTC.

In the example, the timestamp is (that’s in RFC3339 format). The line protocol below is the same data point but without the timestamp. When InfluxDB writes it to the database it uses your server’s local timestamp instead of .

Use the InfluxDB API to specify timestamps with a precision other than nanoseconds, such as microseconds, milliseconds, or seconds. We recommend using the coarsest precision possible as this can result in significant improvements in compression. See the API Reference for more information.

Setup Tip:

Use the Network Time Protocol (NTP) to synchronize time between hosts. InfluxDB uses a host’s local time in UTC to assign timestamps to data; if hosts’ clocks aren’t synchronized with NTP, the timestamps on the data written to InfluxDB can be inaccurate.

Data types

This section covers the data types of line protocol’s major components: measurements, tag keys, tag values, field keys, field values, and timestamps.

Measurements, tag keys, tag values, and field keys are always strings.

Note: Because InfluxDB stores tag values as strings, InfluxDB cannot perform math on tag values. In addition, InfluxQL functions do not accept a tag value as a primary argument. It’s a good idea to take into account that information when designing your schema.

Timestamps are UNIX timestamps. The minimum valid timestamp is or . The maximum valid timestamp is or . As mentioned above, by default, InfluxDB assumes that timestamps have nanosecond precision. See the API Reference for how to specify alternative precisions.

Field values can be floats, integers, strings, or Booleans:

Floats - by default, InfluxDB assumes all numerical field values are floats.

Store the field value as a float:

Integers - append an to the field value to tell InfluxDB to store the number as an integer.

Store the field value as an integer:

Strings - double quote string field values (more on quoting in line protocol below).

Store the field value as a string:

Booleans - specify TRUE with , , , , or . Specify FALSE with , , , , or .

Store the field value as a Boolean:

Note: Acceptable Boolean syntax differs for data writes and data queries. See Frequently Asked Questions for more information.

Within a measurement, a field’s type cannot differ within a shard, but it can differ across shards. For example, writing an integer to a field that previously accepted floats fails if InfluxDB attempts to store the integer in the same shard as the floats:

But, writing an integer to a field that previously accepted floats succeeds if InfluxDB stores the integer in a new shard:

See Frequently Asked Questions for how field value type discrepancies can affect queries.

Quoting

This section covers when not to and when to double () or single () quote in line protocol. Moving from never quote to please do quote:

Never double or single quote the timestamp. It’s not valid line protocol.

Example:

Never single quote field values (even if they’re strings!). It’s also not valid line protocol.

Example:

Do not double or single quote measurement names, tag keys, tag values, and field keys. It is valid line protocol but InfluxDB assumes that the quotes are part of the name.

Example:

To query data in you need to double quote the measurement name and escape the measurement’s double quotes:

Do not double quote field values that are floats, integers, or Booleans. InfluxDB will assume that those values are strings.

Example:

Do double quote field values that are strings.

Example:

Special characters and keywords

Special characters

For tag keys, tag values, and field keys always use a backslash character to escape:

commas

equal signs

spaces

For measurements always use a backslash character to escape:

commas

spaces

For string field values use a backslash character to escape:

double quotes

line protocol does not require users to escape the backslash character but will not complain if you do. For example, inserting the following:

Will be interpreted as follows (notice that a single and double backslash produce the same record):

All other special characters also do not require escaping. For example, line protocol handles emojis with no problem:

Keywords

Line protocol accepts InfluxQL keywords as identifier names. In general, we recommend avoiding using InfluxQL keywords in your schema as it can cause confusion when querying the data.

The keyword is a special case. can be a continuous query name, database name, measurement name, retention policy name, subscription name, and user name. In those cases, does not require double quotes in queries. cannot be a field key or tag key; InfluxDB rejects writes with as a field key or tag key and returns an error. See Frequently Asked Questions for more information.

Writing data to InfluxDB

Getting data in the database

Now that you know all about the InfluxDB line protocol, how do you actually get the line protocol to InfluxDB? Here, we’ll give two quick examples and then point you to the Tools sections for further information.

InfluxDB API

Write data to InfluxDB using the InfluxDB API. Send a request to the endpoint and provide your line protocol in the request body:

For in-depth descriptions of query string parameters, status codes, responses, and more examples, see the API Reference.

CLI

Write data to InfluxDB using the InfluxDB command line interface (CLI). Launch the CLI, use the relevant database, and put in front of your line protocol:

You can also use the CLI to import Line Protocol from a file.

There are several ways to write data to InfluxDB. See the Tools section for more on the InfluxDB API, the CLI, and the available Service Plugins ( UDP, Graphite, CollectD, and OpenTSDB).

Duplicate points

A point is uniquely identified by the measurement name, tag set, and timestamp. If you submit line protocol with the same measurement, tag set, and timestamp, but with a different field set, the field set becomes the union of the old field set and the new field set, where any conflicts favor the new field set.

For a complete example of this behavior and how to avoid it, see How does InfluxDB handle duplicate point?

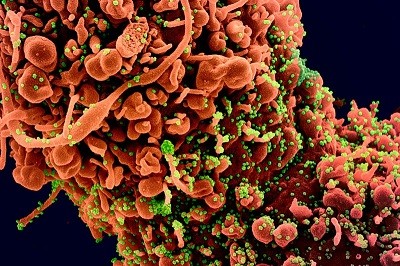

COVID research updates: Good timing might help the immune system to control COVID-19

22 September — Good timing might help the immune system to control COVID-19

People aged 65 and older who are infected with the new coronavirus tend to mount a disorganized immune response — a response that is also associated with severe COVID-19. This could help to explain why the disease strikes older people particularly hard.

The immune system’s ‘adaptive’ branch, which targets specific invaders, has three principle components: antibodies, CD4+ T cells and CD8+ T cells. Alessandro Sette and Shane Crotty at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California studied the adaptive immune response in 24 people whose COVID-19 symptoms ranged from mild to fatal (C. R. Moderbacher et al. Cellhttps://doi.org/ghbwh7; 2020).

The team found that people whose immune systems failed to rapidly launch the entire adaptive immune system tended to have more severe disease than did people in whom all three arms ramped up production simultaneously. An uncoordinated response was particularly common among older people, and could indicate that both antibodies and T cells are important weapons against the coronavirus.

21 September — Business-class passenger spreads coronavirus on flight

Genetic evidence strongly suggests that at least one member of a married couple flying from the United States to Hong Kong infected two flight attendants during the trip.

Researchers led by Leo Poon at the University of Hong Kong and Deborah Watson-Jones at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine studied four people on the early-March flight (E. M. Choi et al. Emerg. Infect. Dis. https://doi.org/d9jn; 2020). Two were a husband and wife travelling in business class. The others were crew members: one in business class and one whose cabin assignment is unknown. The passengers had travelled in Canada and the United States before the flight and tested positive for the new coronavirus soon after arriving in Hong Kong. The flight attendants tested positive shortly thereafter.

The team found that the viral genomes of all four were identical and that their virus was a close genetic relative of some North American SARS-CoV-2 samples — but not of the SARS-CoV-2 prevalent in Hong Kong. This suggests that one or both of the passengers transmitted the virus to the crew members during the flight, the authors say. The authors add that no previous reports of in-flight spread have been supported by genetic evidence.

18 September — Musicians and a monk are tied to superspreading in Hong Kong

An estimated 19% of SARS-CoV-2 infections in Hong Kong seeded 80% of the local transmission of the virus from one person to another, according to an analysis of the virus’s early spread. The analysis also found that viral spread in social settings caused more infections than spread within family households.

In an examination of more than 1,000 coronavirus infections in Hong Kong from late January to late April, Peng Wu at the University of Hong Kong and her colleagues found evidence of multiple ‘superspreading’ events, in which one infected person passed the virus to at least six others (D. C. Adam et al. Nature Med. https://doi.org/d9c4; 2020). Musicians who performed at four Hong Kong bars are thought to have triggered the biggest cluster, which led to 106 cases. Another 19 cases were linked to a temple; one monk there had no symptoms but was found to be infected.

Nearly 70% of the cases did not transmit to anyone, the team found. The analysis also showed that more downstream cases were linked to spread in social settings such as weddings and restaurants than to household spread.

17 September — Immunity to common-cold coronaviruses is short-lived

Natural immunity to coronaviruses that cause the common cold might last for only a few months after infection, according to a study that monitored volunteers’ antibody levels — some for more than three decades.

Previous studies have suggested that immune responses to common-cold coronaviruses protect against reinfection for only a matter of months, although symptoms are often reduced during the second infection. Lia van der Hoek at the University of Amsterdam and her colleagues looked for coronavirus antibodies in blood samples taken every few months from ten individuals, starting in the mid-1980s (A. W. D. Edridge et al. Nature Med. https://doi.org/ghbm79; 2020).

The team used a rise in antibody levels as an indicator of infection. Infections with coronaviruses were least common from June to September, a seasonal pattern that the authors suggest SARS-CoV-2 might follow. The authors found reinfections occurring as early as 6 months after the first infection, and most often at 12 months.

15 September— A groundbreaking guide to making ‘cocktails’ to treat COVID-19

A new method pinpoints every mutation that a crucial SARS-CoV-2 protein could use to evade an attacking antibody. The results could inform the development of antibody treatments for COVID-19.

The immune system produces molecules called antibodies to fend off invaders. Antibodies that bind to an important region of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein can inactivate the viral particles, making such antibodies attractive as therapies. But over time, viruses can accumulate mutations — and some can interfere with antibody binding and allow viral particles to ‘escape’ immune forces.

James Crowe at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, Tennessee, Jesse Bloom at the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Center in Seattle, Washington, and their colleagues created the most detailed map so far of the spike-protein mutations that could prevent binding by ten human antibodies (A. J. Greaney et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/d8zm; 2020). The team then used that information to design three antibody cocktails, each consisting of two antibodies.

In laboratory tests of the cocktails against SARS-CoV-2, the virus did not develop mutations that could escape antibody binding. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

14 September — Kids in US childcare centres spread coronavirus to families

Twelve children infected with the new coronavirus at childcare centres passed the virus on to at least another twelve people between them, according to an analysis of outbreaks in Utah. Among the resulting cases was a woman who had to be hospitalized after presumptive infection by her child.

Cuc Tran at the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, Georgia, and her colleagues investigated outbreaks at three childcare centres in Salt Lake County (Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rept. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6937e3.htm?s_cid=mm6937e3_w; 2020). At all three centres, the first known case was a staff member. Two had gone to work even though a person in their household had shown COVID-19 symptoms.

All 12 infected children, whose ages ranged from 8 months to 10 years, had either mild or no symptoms. Among the children’s close contacts who tested positive were six mothers and three siblings; one eight-month-old baby infected both parents. Not all close contacts were tested, meaning that infections associated with the childcare centres might have been missed, the authors say.

11 September —Nearly half of coronavirus transmission is from people not yet feeling ill

Some three-quarters of incidents of SARS-CoV-2 transmission occur in the few days before or after the onset of symptoms in the person who passes on the virus.

Luca Ferretti at the University of Oxford, UK, and colleagues studied 191 cases of SARS-CoV-2 transmission from an infected person to an uninfected person. The team analysed the timing of the transmitting person’s initial infection and onset of symptoms, and when that person spread the infection to someone else (L. Ferretti et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/d8ms; 2020).

They found that roughly 40% of transmission events occurred before the onset of symptoms, and around 35% took place on the day that symptoms appeared or on the following day.

The researchers say their findings underscore the importance of mass testing, contact tracing and physical distancing to prevent transmission from pre-symptomatic people, as well as self-isolation for at least two days at the first sign of symptoms such as cough, fever, fatigue and loss of smell — however mild.

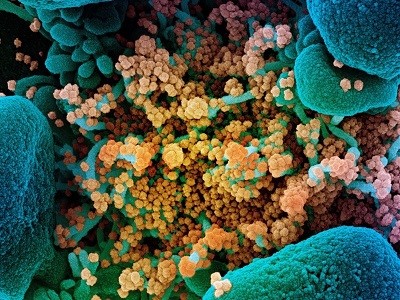

10 September — Surprise! A host of tantalizing new SARS-CoV-2 proteins is unveiled

Researchers have discovered nearly two dozen previously unknown proteins encoded by SARS-CoV-2 — and their role during infection is mostly mysterious.

Until now, SARS-CoV-2’s RNA genome was known to hold the instructions for making 29 proteins, such as the spike protein that helps viral particles to infect cells, and a variety of viral proteins that become active inside cells. But scientists were uncertain whether the virus had more than those 29.

To identify further proteins, Noam Stern-Ginossar at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, and her colleagues sequenced SARS-CoV-2 RNA bound to protein-making machines called ribosomes inside infected cells (Y. Finkel et al. Naturehttps://doi.org/d8pb; 2020). This scan turned up 23 previously unknown proteins, including some that are entirely new and others that are shortened or extended versions of known proteins.

Some of the newfound proteins might control production of known viral molecules, but the role of many is unknown.

9 September — The immune-cell traits that could predict severe COVID-19

Immune cells called neutrophils are more likely to be primed for action in people who will eventually develop severe COVID-19 than in those who are will go on to become only mildly ill, according to a machine-learning analysis of data from 3,300 people. If the results can be reproduced, they could aid early identification of the people most likely to become critically ill.

Neutrophils comprise an important part of the body’s rapid response to infection, but can also damage uninfected tissue. Hyung Chun of Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, and his colleagues used machine learning to analyse proteins in blood plasma taken from people hospitalized with COVID-19 (M. L. Meizlish et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/d8hm; 2020).

Several immune proteins that are associated with neutrophils were found at higher levels in the plasma of people who later became critically ill than in those whose illness did not become severe. A subsequent analysis of health records from about 3,300 people showed that high neutrophil counts were associated with increased COVID-19 mortality. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

8 September — Kids ravaged by COVID-19 show unique immune profile

Most children infected with the new coronavirus show few signs of illness, if any. But a few children are struck by a severe form of COVID-19 that can cause multiple organ failure and even death. Now, scientists have begun to tease out the biology of this rare and devastating condition, called multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, or MIS-C.

Doctors have diagnosed hundreds of cases of MIS-C, which shares some similarities with the childhood illness Kawasaki’s disease. To understand MIS-C’s biological profile, Petter Brodin at the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm and his colleagues looked at 13 children with MIS-C, 28 children with Kawasaki’s disease and 41with mild COVID-19 (C. R. Consiglio et al. Cellhttps://doi.org/d8fh; 2020). The researchers found that compared with children with Kawasaki’s disease, those with MIS-C have lower levels of an immune chemical called IL-17A, which has been implicated in inflammation and autoimmune disorders.

Unlike all the other children studied, children with MIS-C had no antibodies to two coronaviruses that cause the common cold. This deficit might be implicated in the origins of their condition, the authors say.

4 September — Powerful new evidence links steroid treatment to lower deaths

People severely ill with COVID-19 are less likely to die if they are given drugs called corticosteroids than people who are not, according to an analysis of hospital patients on five continents.

Earlier findings showed that the steroid dexamethasone cut deaths in people with COVID-19 on ventilators. To examine the effects of steroids in general, Jonathan Sterne at the University of Bristol, UK, and his colleagues did a meta-analysis that pooled data from seven clinical trials; each of the seven studied the use of steroids in people who were critically ill with COVID-19 (REACT Working Group J. Am. Med. Assoc.https://doi.org/d7z8; 2020). The trials included more than 1,700 people across 12 countries.

The team analysed participants’ status 28 days after they were randomly assigned to take either a steroid or a placebo. The risk of death was 32% for those who took a steroid and 40% for those who took a placebo. The authors say that steroids should be part of the standard treatment for people with severe COVID-19.

3 September — In a first, genomics shows that mink can pass SARS-CoV-2 to humans

An investigation of Dutch mink farms has found the first documented cases of animal-to-human transmission of SARS-CoV-2.

After SARS-CoV-2 outbreaks among farmed mink were first detected in late April, Marion Koopmans at Erasmus Medical Centre in Rotterdam, the Netherlands, and her colleagues used genome sequencing to track outbreaks among animals and workers at 16 mink farms (B. B. O. Munnink et al. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/d7xn; 2020). The team tested 97 farmworkers and their contacts, and found evidence for SARS-CoV-2 infection in 66 of them.

Genetic analysis suggested that workers had introduced SARS-CoV-2 to mink, which spread the virus back to workers, who might then have passed it on to other people. Outbreaks at mink farms have been detected in Denmark, Spain and the United States, and the researchers say unchecked spread could lead to the animals becoming a reservoir for human infections. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

2 September — Antibodies persist for months rather than dwindling

A sweeping survey in Iceland shows that antibodies against the new coronavirus endure in the body for four months after infection, countering earlier evidence suggesting that these important immune molecules quickly disappear.

After a pathogen invades, the immune system produces proteins called antibodies to fight off the intruder. Scientists do not know whether people who generate antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 are protected from reinfection, nor do they know how long those antibodies persist.

Kari Stefansson at deCODE Genetics–Amgen in Reykjavik and his colleagues measured the levels of SARS-CoV-2 antibodies in the blood of roughly 30,000 people, including more than 1,200 who had tested positive for the virus and recovered from COVID-19 (D. F. Gudbjartsson et al. N. Engl. J. Med.https://doi.org/gg9hbt; 2020). Roughly 90% of the recovered people had antibodies against the virus. Their antibody levels rose during the two months after diagnosis, plateaued and then remained at the same level for the duration of the study.

The results also show that the virus has infected only 0.9% of the population, leaving Iceland “vulnerable to a second wave of infection”, the authors warn.

1 September — Even octogenarians develop potent antibodies

As the new coronavirus ripped through several care homes in England, more than 80% of the residents mounted an antibody response to the virus, including 82% of those over the age of 80.

During outbreaks at six residential and nursing homes, Shamez Ladhani at Public Health England in London and his colleagues tested more than 500 residents and staff for SARS-CoV-2 infection (S. N. Ladhani et al. Preprint at medRxiv https://doi.org/d7p2; 2020). About five weeks later, the team tested many of the same people for antibodies to SARS-CoV-2 and in particular for neutralizing antibodies, potent molecules that can block the virus from infecting cells

The team found that roughly the same proportion of staff members and care-home residents had formed antibodies to the coronavirus. And neutralizing antibodies had developed in almost 90% of both staff members and residents, including more than 80% of people over the age of 80.

The authors caution that it is not clear whether antibodies against the virus guard against reinfection. The findings have not yet been peer-reviewed.

28 August ― COVID-19 testing helps sleep-away summer camps to avoid outbreaks

Rigorous SARS-CoV-2 testing and infection-control measures prevented outbreaks at four overnight camps in Maine that hosted hundreds of children between mid-June and mid-August.

Laura Blaisdell at the Maine Medical Center in Portland and colleagues report that the four sleep-away camps asked all attendees — both campers and staff — to be tested for SARS-CoV-2 before arrival (L. L. Blaisdell et al. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm6935e1.htm?s_cid=mm6935e1_w; 2020). Shortly after arrival, attendees were re-tested for the virus. They were also assigned to small cohorts and spent the first 14 days of camp quarantining with members of their cohort.

Of more than 1,000 attendees, 2 staff members and one camper tested positive at camp and were isolated until they tested negative. The 30 people in the camper’s cohort were quarantined; all tested negative for the virus during quarantine. The authors say that the virus did not spread beyond the three infected attendees.

27 August — Why infected primary-school pupils could be hard to spot

Children aged 6 to 13 are less likely to have symptoms of COVID-19 than those who are younger or older, according to a study of nearly 400 infected people under the age of 21.

Matthew Kelly and his colleagues at Duke University School of Medicine in Durham, North Carolina, studied 382 children and young adults who had had close contact with a person infected with SARS-CoV-2 (J. H. Hurst et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d7cb; 2020). Roughly three-quarters of the study participants tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 either before or during the study.

Only 61% of infected children aged 6 to 13 showed symptoms, compared with 75% of infected study participants under age 6 and 76% of those over age 13. Children aged 6–13 who did feel ill tended to have milder symptoms than older and younger study participants.

Nearly one-third of infected children with an infected sibling did not have close contact with an infected adult, implying that the virus had spread from child to child.

Screening systems at schools and day-care centres should account for age-related differences in symptoms, the authors say. The results have not yet been peer reviewed.

26 August — Sex differences in the COVID-19 immune response might drive men’s high risk

Variations in the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 could explain why men are more likely to be hospitalized and die of COVID-19 than are women.

Akiko Iwasaki at Yale University School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and colleagues studied the immune responses of 98 men and women infected with SARS-CoV-2. All had mild to moderate symptoms (T. Takahashi et al.Nature http://doi.org/d7gb; 2020). The researchers noticed that male participants’ typical immune response to infection differed from that of female participants, which could explain the more severe disease often observed in men. (Nature recognizes that sex and gender are neither binary nor fixed.)

The team found that in general, men had higher levels of certain inflammation-causing proteins known as cytokines and chemokines circulating in their blood than had women. By contrast, women tended to have a stronger response from immune cells known as T cells than did men. In men, an increase in symptom severity over time was associated with a weak T-cell response; in women, it was associated with increased amounts of inflammatory cytokines.

The study proposes taking sex into account when treating people with COVID-19.

25 August ― Reinfection with SARS-CoV-2 is confirmed for the first time with genetic evidence

A man in Hong Kong who was ill with COVID-19 in March was infected by a different variant of the new coronavirus several months later — the first evidence for reinfection that is supported by genetic analysis.

People infected with SARS-CoV-2 mount an immune response, which scientists think probably prevents most reinfections. The durability of this protection is unclear, and a documented case of reinfection would signal that immunity can wane. But previously reported reinfections have been found to relate instead to prolonged shedding of the virus or its genetic material

Kwok-Yung Yuen and his colleagues at the University of Hong Kong identified a 33-year-old man who recovered from COVID-19 in April and tested positive again more than 4 months later, after returning from Spain via the United Kingdom (K. K.-W. To et al. Clin. Infect. Dis.http://doi.org/d7ds; 2020). Genetic sequencing suggested that the second infection was caused by a virus that was genetically distinct from the one responsible for his initial bout.

The man never developed symptoms from the second infection, but his immune system responded by producing a fresh batch of antibodies.

21 August— Vaccines given through the nose could protect against infection

Studies in mice and monkeys show that nasal vaccinations can shield the animals from the new coronavirus — and that such vaccinations might be more effective than an injected form of the same vaccine.

David Curiel and Michael Diamond at Washington University School of Medicine in St Louis, Missouri, and their colleagues created a candidate vaccine encoding the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, which the virus uses to invade cells (A. O. Hassan et al. Cellhttp://doi.org/d63k; 2020). The researchers then gave the vaccine to bioengineered mice that had human receptors for the protein.

After being injected with the vaccine and then exposed to SARS-CoV-2, mice showed no infectious virus in their lungs — but their lungs did harbour small amounts of viral RNA. By contrast, mice that had the vaccine inserted up their noses before exposure had no measurable viral RNA in their lungs. This and other evidence suggests that the nasal vaccine entirely warded off infection, the authors say.

Ling Chen at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University in China and colleagues developed another vaccine encoding the spike protein (L. Feng et al. Nature Commun. 11, 4207; 2020). The researchers found that both nasal and injected forms of the vaccine protected rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) from infection. The authors say that a vaccine that can be given by nose might allow people to vaccinate themselves.

20 August— A coronavirus mutation is tied to less severe illness

A SARS-CoV-2 mutation that appeared in East Asia early in the pandemic is linked to symptoms milder than those caused by the unmutated version of the virus.

In early 2020, researchers in Singapore identified a cluster of COVID-19 cases caused by a SARS-CoV-2 variant missing a chunk of RNA that spanned two genes, ORF7b and ORF8. To determine the consequences of this change, called a deletion, Lisa Ng at the Singapore Immunology Network and colleagues compared people infected with viruses carrying the deletion with those infected by normal viruses (B. E. Young et al. Lancethttp://doi.org/d6x7; 2020).

None of the 29 people whose viruses had the mutation needed supplemental oxygen, but 26 of the 92 people whose viruses lacked the mutation did. Viruses carrying the deletion haven’t been detected since March — possibly owing to infection-control measures.

The virus responsible for the 2002–04 outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) acquired a similar deletion in the ORF8 gene, suggesting that this might be an important adaption to infecting humans, the authors say.

Correction: An earlier version of this article said researchers identified a SARS-CoV-2 variant missing a chunk of DNA.

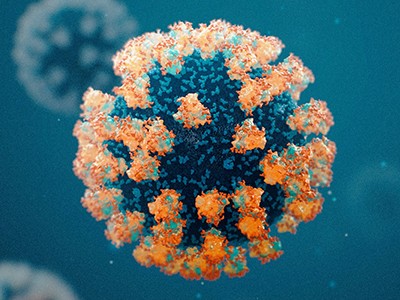

19 August — An unprecedented map charts a key viral protein

For the first time, researchers have mapped the 3D shape of spike proteins that are part of intact SARS-CoV-2 particles.

Spike proteins decorate the surface of coronaviruses and lock onto host receptors, such as ACE2, to gain entry to cells. The first structures of SARS-CoV-2’s spike were gleaned from modified proteins that had been expressed in cells and then purified. To check these models John Briggs at the Medical Research Council Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge, UK, and colleagues collected viral particles from infected cells and determined the shape of their spike proteins using electron microscopy (Z. Ke et al. Naturehttp://doi.org/d6sf; 2020).

These structures closely resembled the ones determined from purified forms. In both, the spike protein can adopt either a ‘closed’ confirmation or an ‘open’ one, which allows it to bind to a receptor. Studying the structure in viral particles could help to explain how spike-binding antibodies block infection, the researchers say.

17 August — Sailors furnish first evidence that antibodies protect humans against re-infection

A massive COVID-19 outbreak on a US fishing boat spared crew members who already had antibodies against the new coronavirus, providing what scientists say is the first direct evidence that these antibodies protect people against being reinfected.

After a viral infection, the immune system makes compounds called neutralizing antibodies that can attack the virus if it invades again. But previous research had not determined whether such antibodies can shield humans from SARS-CoV-2 reinfection.

Alexander Greninger at the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle and his colleagues tested the crew of a US fishing vessel for SARS-CoV-2 and for antibodies to the virus (A. Addetia et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d6qm; 2020). Just before the ship’s departure, the researchers tested 120 of the 122 crew members and found that all were negative for SARS-CoV2, but an outbreak hit the ship soon after it left shore.

Post-voyage testing showed that 104 members of the 122-person crew were infected. None of those who were infected and had been tested before embarking had shown neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2.

But all three crew members who did have such antibodies before departure escaped infection, providing statistically significant evidence that neutralizing antibodies acquired during SARS-CoV-2 infection protect against reinfection, the authors say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

7 August — For fast and low-cost COVID-19 testing, just spit

A quick, cheap and painless test that detects SARS-CoV-2 RNA in spit could be used for mass testing.

Chantal Vogels at Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut, and colleagues developed a simple saliva test — called SalivaDirect — to address the growing demand for extensive testing as lockdowns lift (C. B. F. Vogels et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d5s3; 2020).

Compared with the gold-standard nose and throat swab, the saliva test is less invasive, does not need to be conducted by a trained professional and avoids the use of scarce chemicals that are needed to store and extract viral RNA. In validation experiments, SalivaDirect detected 32 out of 34 samples that tested positive in nose and throat swabs, and 30 out of 33 negative samples.

The researchers estimate a cost-per-spit of US$1.29–$4.37, and have requested that the United States Food and Drug Administration authorize the test for emergency use.

6 August — Immune reaction to some common colds might provide protection

Some immune cells that recognize coronaviruses that cause the common cold also respond to SARS-CoV-2, the coronavirus responsible for the COVID-19 pandemic.

Previous studies have found that some people who have never been exposed to SARS-CoV-2 nevertheless have immune cells called memory T cells that can recognize the virus. Daniela Weiskopf and Alessandro Sette at the La Jolla Institute for Immunology in California analysed such T cells, and found that they recognize particular sequences of several SARS-CoV-2 proteins (J. Mateus et al. Sciencehttp://doi.org/d5v5; 2020).

The team then identified similar sequences in common-cold coronaviruses, and showed these sequences could activate some T cells that also respond to SARS-CoV-2. The findings add weight to the hypothesis that existing immunity to cold coronaviruses could contribute to differences in COVID-19 severity, but further studies are required to support that conclusion.

5 August — Antibody blend protects monkeys and hamsters from viral symptoms

A mixture of two human antibodies against the new coronavirus shows promise in animal tests for preventing and treating COVID-19.

Neutralizing antibodies are immune molecules that can attach to viruses and disable them. Christos Kyratsous at Regeneron Pharmaceuticals in Tarrytown, New York, and his colleagues made a cocktail of two neutralizing antibodies that bind SARS-CoV-2. They gave the cocktail to rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta), which become mildly ill when infected.

The researchers found that compared to animals that took a placebo, monkeys that received the antibody combination were less likely to develop pneumonia and, if they did, had less lung damage. This was true in monkeys that took the antibodies either before or after receiving a dose of the virus (A. Baum et al. Preprint at bioRxiv http://doi.org/d5r9; 2020).

Unlike macaques, Syrian golden hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) infected with SARS-CoV-2 become acutely ill. But hamsters dosed with virus lost less weight — or even gained weight — compared with control rodents if given the antibody cocktail before or after receiving a dose of the virus. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

3 August — Summer-camp outbreak infects more than 200 children

Despite measures to prevent the spread of the new coronavirus, at least 250 campers and staff members tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 after attending an overnight camp in the US state of Georgia.

Christine Szablewski at the Georgia Department of Public Health in Atlanta and her colleagues investigated the outbreak, which began two days after the first campers’ arrival on 21 June (C. M. Szablewski et al. Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. http://doi.org/d5ms; 2020). All campers and staff were required to test negative for the virus fewer than 13 days before arrival, and campers did not mix with those sleeping in other cabins. Campers were not required to wear masks.

The researchers found that nearly 100 staff members — many of them teenagers — tested positive in the two weeks after leaving camp. So did 168 campers, including half of those aged between 6 and 10. Factors contributing to the outbreak included the large number of campers sleeping in each cabin and what the researchers describe as “daily vigorous singing and cheering”.

30 July — Vaccine candidate protects monkeys from infection

An experimental coronavirus vaccine seems to have completely prevented infection in most monkeys that received the jab.

Hanneke Schuitemaker at Janssen Vaccines and Prevention in Leiden, the Netherlands, Dan Barouch at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, Massachusetts, and their colleagues gave 32 rhesus macaques (Macaca mulatta) a single dose of one of 7 vaccines (N. B. Mercado et al. Naturehttp://doi.org/d5d4; 2020). Each vaccine comprised a weakened respiratory virus coding for one of seven forms of SARS-CoV-2’s spike protein.

After vaccination, nearly all the monkeys made neutralizing antibodies — powerful immune molecules that can block infection — and T cells that trigger other immune responses. When monkeys were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the most potent of the vaccines prevented lung infection in six out of six animals that received it, and nasal infection in five out of six.

Across all the vaccinated monkeys, levels of neutralizing antibodies were associated with protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection, but levels of T cells were not.

29 July— Immune cells against the virus are found in unexposed people

Immune cells called T cells are prepared to attack the new coronavirus not only in people with COVID-19, but also in some who have not been exposed to the virus.

At first, researchers studying the immune response to SARS-CoV-2 focused mostly on the immune molecules called antibodies, but T cells offer another possible route to immunity. Andreas Thiel at Charité University Hospital Berlin and his colleagues surveyed blood samples for T cells that react to the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein (J. Braun et al. Naturehttp://doi.org/d5bv; 2020).

The team found such cells in 83% of study participants with COVID-19, as well as 35% of healthy blood donors who had not been exposed to SARS-CoV-2. The authors speculate that the reactive T cells might have been generated in healthy donors during past infections with related coronaviruses, but it remains unclear whether these cells offer protection against SARS-CoV-2.

28 July — Mutations allow virus to elude antibodies

Mutations in SARS-CoV-2 might help the virus to thwart potent immune molecules.

The blood of many people who recover from COVID-19 contains immune-system molecules called neutralizing antibodies that disable particles of the new coronavirus. Most such antibodies recognize the new coronavirus’s spike protein, which the virus uses to infect cells. Researchers hope that these molecules can be used as therapies, and can be elicited by vaccines.

Theodora Hatziioannou and Paul Bieniasz at the Rockefeller University in New York City and their colleagues engineered a version of the vesicular stomatitis virus, which infects livestock, to make the spike protein. They then grew the virus in the presence of neutralizing antibodies (Y. Weisblum et al. Preprint at bioRxiv http://doi.org/d439; 2020). The spike protein in the engineered viruses acquired mutations that allowed the viruses to escape recognition by a range of neutralizing antibodies.

The team also found these mutations in SARS-CoV-2 samples from infected people around the world, although at very low frequencies. Treatment ‘cocktails’ of multiple neutralizing antibodies, each recognizing a different part of the spike protein, could stop the virus from evolving resistance to these molecules, the authors suggest. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

27 July— The power of China’s virus-control campaign is seen in pattern of symptoms

In China, a key metric of epidemics called the serial interval shrank drastically soon after the new coronavirus’s arrival — a finding that underscores the success of China’s testing and isolation efforts.

The serial interval is the average time between the onset of symptoms in a chain of people infected by a pathogen. Benjamin Cowling at the University of Hong Kong and his colleagues modelled the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in China and found that the serial interval plummeted from 7.8 days to 2.6 days over a 5-week period starting on 9 January (S. T. Ali et al. Sciencehttp://doi.org/gg5mpc; 2020).

The researchers say that early isolation of cases prevented transmission that would otherwise have occurred later in an infectious period, leading to fewer cases and slowing the spread of the virus. As a result, most of the remaining transmissions occurred either before infected people showed symptoms or early in the symptomatic phase, and the serial interval shrank.

The authors suggest the serial interval distribution be used in real time to track the changing transmissibility of the virus.

24 July — Dogs’ and cats’ infection rates mirror those of people

Cats and dogs are just as likely to be infected with SARS-CoV-2 as people are, according to a survey in northern Italy that is the largest study of pets so far.

Nicola Decaro at the University of Bari and his colleagues took nose, throat or rectal swabs of 540 dogs and 277 cats in northern Italy between March and May (E. I. Patterson et al. Preprint at bioRxiv http://doi.org/d4r7; 2020). The animals lived in homes with infected people, or in regions severely affected by COVID-19.

None of the pets tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 viral RNA, but in further tests of antibodies against the virus circulating in the blood of some animals, the researchers found that around 3% of dogs and 4% of cats showed evidence of previous infection.

Infection rates among cats and dogs were comparable with those among people in Europe at the time of testing, suggesting that it is not unusual for pets to be infected. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

24 July — Virus rips through Israeli school after masking is suspended

More than 150 students at an Israeli secondary school were infected by the new coronavirus after students were allowed to remove their masks during a heat-wave.

Roughly 10 days after Israeli schools fully reopened on 17 May, two students at a secondary school in Jerusalem were diagnosed with COVID-19. Chen Stein-Zamir at the Ministry of Health in Jerusalem and her colleagues investigated the resulting outbreak and found that 153 students and 25 members of staff had become infected (C. Stein-Zamir et al. Euro Surveill.http://doi.org/d4sw; 2020). By mid-June, a further 87 cases had occurred among the close contacts of people infected through the school outbreak.

The virus’s spread was probably aided by a heat-wave that occurred between 19 and 21 May, prompting heavy use of air-conditioning and a suspension of the requirement that students wear face masks. Crowding might also have contributed: each of the school’s classrooms held 35 to 38 students, resulting in space allotments of 1.1–1.3 square metres per student.

22 July — Severely ill people yield diverse trove of powerful antibodies

Scientists have identified a diverse group of antibodies that block the new coronavirus’s ability to infect cells — even when applied in low doses.

The immune-system proteins called neutralizing antibodies interfere with hostile microbes trying to enter target cells. David Ho at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York City and his colleagues studied neutralizing antibodies from the plasma of five people with severe cases of COVID-19 (L. Liu et al. Naturehttp://doi.org/d4md; 2020).

Nineteen antibodies proved highly effective at preventing SARS-CoV-2 infection of cell samples. A small dose of one of the antibodies protected golden Syrian hamsters (Mesocricetus auratus) from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

The 19 antibodies attach to a variety of locations on the coronavirus spike protein. A therapy made from antibodies that fasten onto the spike protein at multiple sites could be difficult for the virus to evade through mutation.

21 July — Viral levels could help to target treatment

The amount of viral RNA in the nose and throat of a person infected with the new coronavirus could help clinicians to decide how best to treat them, according to an analysis of thousands of swabs taken at a hospital in Switzerland.

Onya Opota and his colleagues at Lausanne University Hospital analysed the viral load — the amount of virus in a standard volume of material — of samples taken from 4,172 people infected with SARS-CoV-2 between 1 February and 27 April (D. Jacot et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d4b8; 2020). They noticed two distinct stages of COVID-19. Early in the disease, people have high viral loads, which tend to decline gradually as the disease progresses. This later stage is typically characterized by inflammation. The decline of viral loads could thus serve as a cue to start treating infected people with anti-inflammatory drugs.

But the researchers found no correlation between viral load and the severity of disease, suggesting that it is not a good predictor of a patient’s outcome. The research has not yet been peer reviewed.

16 July — Antiviral antibodies peter out within weeks after infection

Key antibodies that neutralize the effects of the new coronavirus fall to low levels within months of SARS-CoV-2 infection, according to the most comprehensive study yet.

Neutralizing antibodies can block a pathogen from infecting cells. But such antibody responses against coronaviruses often wane after just a few weeks.

Katie Doores at King’s College London and her colleagues monitored the concentration of neutralizing antibodies against SARS-CoV-2 in 65 infected people for up to 94 days (J. Seow et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d3s2; 2020). In a preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed, the team reports that at the peak of antibody production, people with severe COVID-19 symptoms had higher levels of antibodies than had people with mild disease.

However, in most people, antibody levels began to fall about a month after symptoms appeared, sometimes to nearly undetectable levels — raising questions about the durability of vaccines designed to promote the production of neutralizing antibodies.

15 July — Positive trial results raise hopes for a top vaccine candidate

A leading COVID-19 vaccine candidate generates an immune response against the virus and causes few side effects, according to preliminary data from a phase I safety study with 45 participants.

The vaccine is being co-developed by Moderna in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. It consists of RNA instructions that prompt human cells to make the virus’s spike protein, generating an immune response.

Lisa Jackson at Kaiser Permanente Washington Health Research Institute in Seattle and her colleagues gave participants two injections, administered four weeks apart, of one of three different doses of the vaccine (L. A. Jackson et al. N. Engl. J. Med. http://doi.org/d3tt; 2020). Most side effects were mild, although three participants who got the highest dose experienced worse complications, such as a high fever.

After the injections, all participants produced immune proteins called antibodies capable of recognizing the SARS-CoV-2 virus, as well as ‘neutralizing antibodies’ that can block infection. A 30,000-participant phase III trial to test whether the vaccine can prevent COVID-19 is set to begin in late July.

15 July — Severe COVID-19 has a telltale immune profile

Scientists have identified an immune-system signature in people with serious COVID-19 — a finding that could inform the development of treatments for the disease.

Benjamin Terrier at the University of Paris and his colleagues analysed blood samples from 50 people infected with SARS-CoV-2 (J. Hadjadj et al.Sciencehttp://doi.org/gg4vjx; 2020). Compared to the individuals with mild or moderate symptoms, those with severe disease produced fewer antiviral proteins called interferons and more inflammatory molecules. The researchers also found that blood levels of a specific interferon decreased just before participants had to be taken to intensive-care units.

The results suggest that reduction of interferon levels in the blood is a hallmark of severe COVID-19. Treatments that counter inflammation and increase levels of interferons could help people with the disease, the researchers say.

13 July — Virus’s US invasion might have started in 2019

The new coronavirus spread across much of the interior of the United States by tagging along with people moving from state to state, but US coastal regions were seeded with SARS-CoV-2 imported from other countries — perhaps in 2019, according to models.

Alessandro Vespignani at Northeastern University in Boston, Massachusetts, and his colleagues studied air traffic, commuting patterns and other data to understand how and when the coronavirus took hold in the United States (J. T. Davis et al. Preprint at medRxiv http://doi.org/d3mf; 2020). The team found that in several coastal states, international travel drove introduction of the virus. In California and New York, SARS-CoV-2 might have begun circulating as early as December 2019.

But in many non-coastal states, domestic travellers rather than international visitors were the source of the first wave of infections. Infections spread across the country from late January to early March but were largely undetected, the authors say. The findings have not yet been peer reviewed.

10 July — Massive contact-tracing effort finds hundreds of cases linked to nightclubs

Mobile phone and credit card data helped to identify nearly 250 coronavirus infections linked to a fast-moving outbreak that began in a popular nightclub district in Seoul.